Devils in disguise: The dark market for cryptid guitarfish

In one of the murky, ill-patrolled areas of global trade, a lucrative market for aliens and devils exists.

With leathery, twisted wings, devil’s horns and tails to match, these otherworldly creatures seem plucked from fantastical tales of towering dragons, and monsters that roam the inky depths.

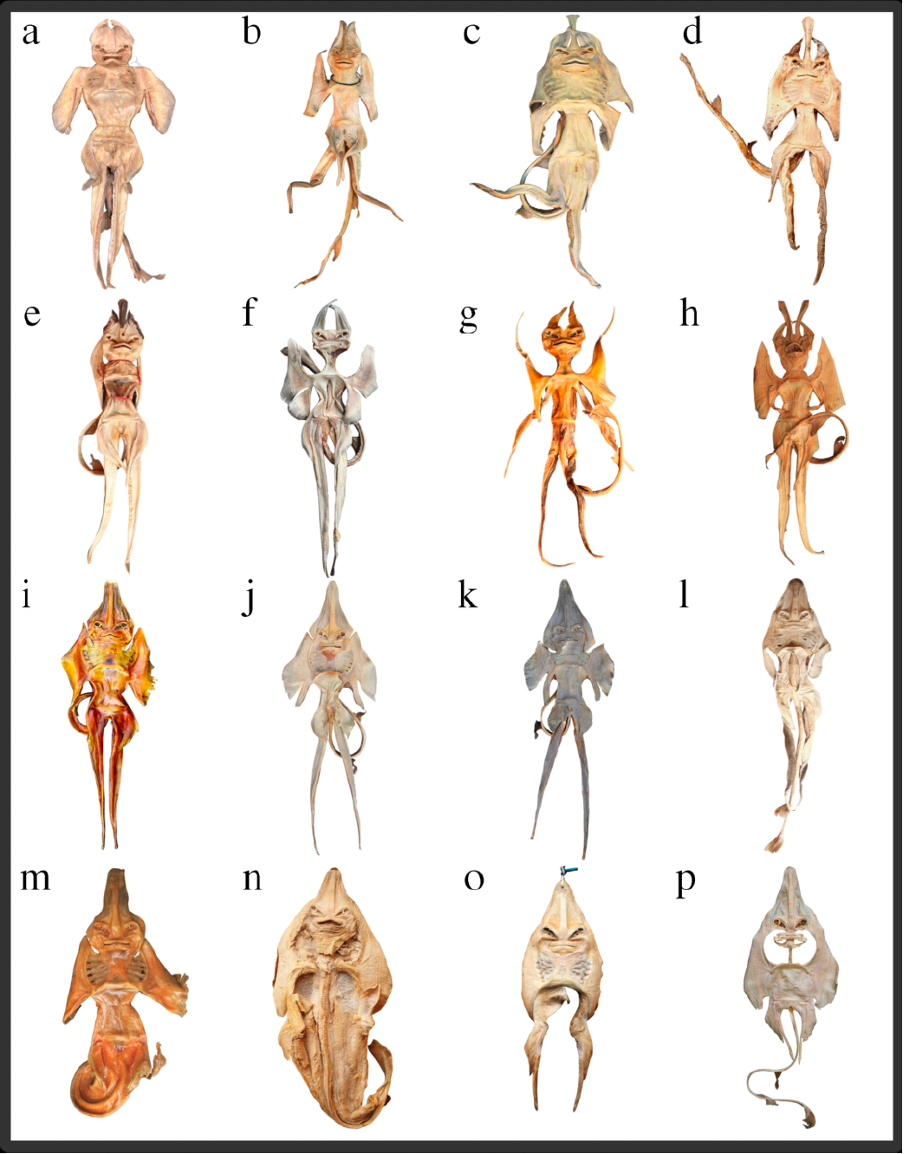

In reality, what has been described is not a strange cosmic being or a legend come to life, but rather one of the many variations of ‘cryptids’, or animals believed by some to exist, but whose existence remains unverified. A ‘cryptid batoid’ is a modified and stuffed guitarfish, the transformation of which involves cutting and drying the fish, removing rostral cartilage and creating a neck-like appendage that makes the animal look like a new, unsubstantiated species. But why is there a market for such peculiar fabrications, and what does this mean for the animal populations involved? Bryan Huerta explores this in his recent paper ‘The invisible trade of cryptid yet imperiled guitarfishes’.

Photo © Bryan Huerta

Across civilisations, the preternatural, fantastical, grotesque and mythical have captured the imagination of the public. From the basilisks of ancient Greek and Babylonian societies to the chupacabras of Latin America and the bunyips of Australia, these cryptids have inspired the crafting of man-made counterparts using animal carcasses and body parts. Frequently created as a hoax, these oddities can be drawn from abundant, healthy populations – like the whisky-drinking, cowboy-mimicking cryptid in North American folklore, the jackalope, which is fashioned from the body of a rabbit or hare and adorned with the antlers of a deer. But in other cases, they involve threatened species, turning the macabre practice into a conservation concern.

Skates and rays, one of the most threatened marine fish groups in the ocean, have long been the basis of the distorted architecture of cryptids; the first known illustration dates from as long ago as 1558. Around the world these fabrications are known as Jenny Hanivers (Australia, Europe and the USA), garadiávolos, diablitos or pez Diablo (Latin America), devil fish (USA and Europe) or rayas chupacabras (Guatemala). For centuries, skates dominated the cryptid batoid trade, but in the mid-1900s guitarfish (family Rhinobatidae) took their place.

The shift to guitarfish species reflects their more human-like features, which make them easier to mould into ‘alien-like’ or ‘devil-like’ cryptids. Sixteen distinct forms of these creations have been identified, falling into these two broad categories. Between the 1950s and early 2000s, cryptid batoids grew in popularity, captivating diverse cultures and even inspiring renowned artists and scientists alike. Over time, these fabricated legends became more profitable, their mystique fuelling demand.

Photo © Bryan Huerta

Sold as curiosities, hoaxes or even alternative medicines, modified guitarfish are significantly more valuable than their fresh counterparts. For example, in traditional Mexican medicine, cryptid guitarfish are believed to cure ailments such as cancer and arthritis, further driving their appeal. These creations can fetch as much as US$500, though most are priced between US$15 and US$200. By comparison, a whole, fresh guitarfish might sell for as little as US$2 in Mexican fish markets. While cryptid batoids are becoming more widely available through platforms such as Facebook, Etsy and other online stores in the USA, Canada and Europe, little is known about their use and value in many other countries.

Despite the growing market, trade in guitarfish is barely regulated and the species are highly susceptible to overfishing. More than half of them are listed as threatened on the IUCN Red List, and in February 2023 they were added to CITES Appendix II. However, the species-specific identities of traded cryptid guitarfishes remain poorly documented. Molecular techniques, which involve taking tissue samples and sequencing the DNA found within, have proven useful in helping to control other wildlife trades, such as the shark fin trade, and are needed for accurate identification in the cryptid batoid market. In addition, raising awareness of the ecological consequences of this practice is critical to curbing the demise of this group.

A fresh guitarfish recovered at a fish market in Mexico to be traded for its meat. Photo © Bryan Huerta

The story of aliens and devils is not one about creatures that hail from an infernal pit or a galaxy far, far away, but rather the ill-regulated harvest of animals from our own planet, whose persistence is threatened by practices that contribute to their plight. It underscores the intersection of human fascination, cultural practices and conservation challenges. As legends evolve and markets expand, the urgent task remains to protect these creatures from exploitation while educating ourselves about their true nature and ecological importance.

Reference

Bryan L. Huerta-Beltrán, J. Marcus Drymon, Amanda E. Jargowsky, Peter M. Kyne, Nicole M. Phillips. An invisible trade in imperiled guitarfishes. Conservation Biology. doi.org/10.1111/cobi.70087

View online here: https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cobi.70087