Conserving sharks & coastal livelihoods in Indonesia

Carrying out conservation is complex. Often, something that seems like a straightforward solution on the surface in reality goes much deeper.

Small-scale fisheries are a prime example. These fisheries alone catch about half of the world’s seafood, providing livelihoods for millions of people – and food for billions. And they have cultural and social significance too. Unfortunately, though, these fisheries often catch endangered sharks and rays, both accidentally and on purpose.

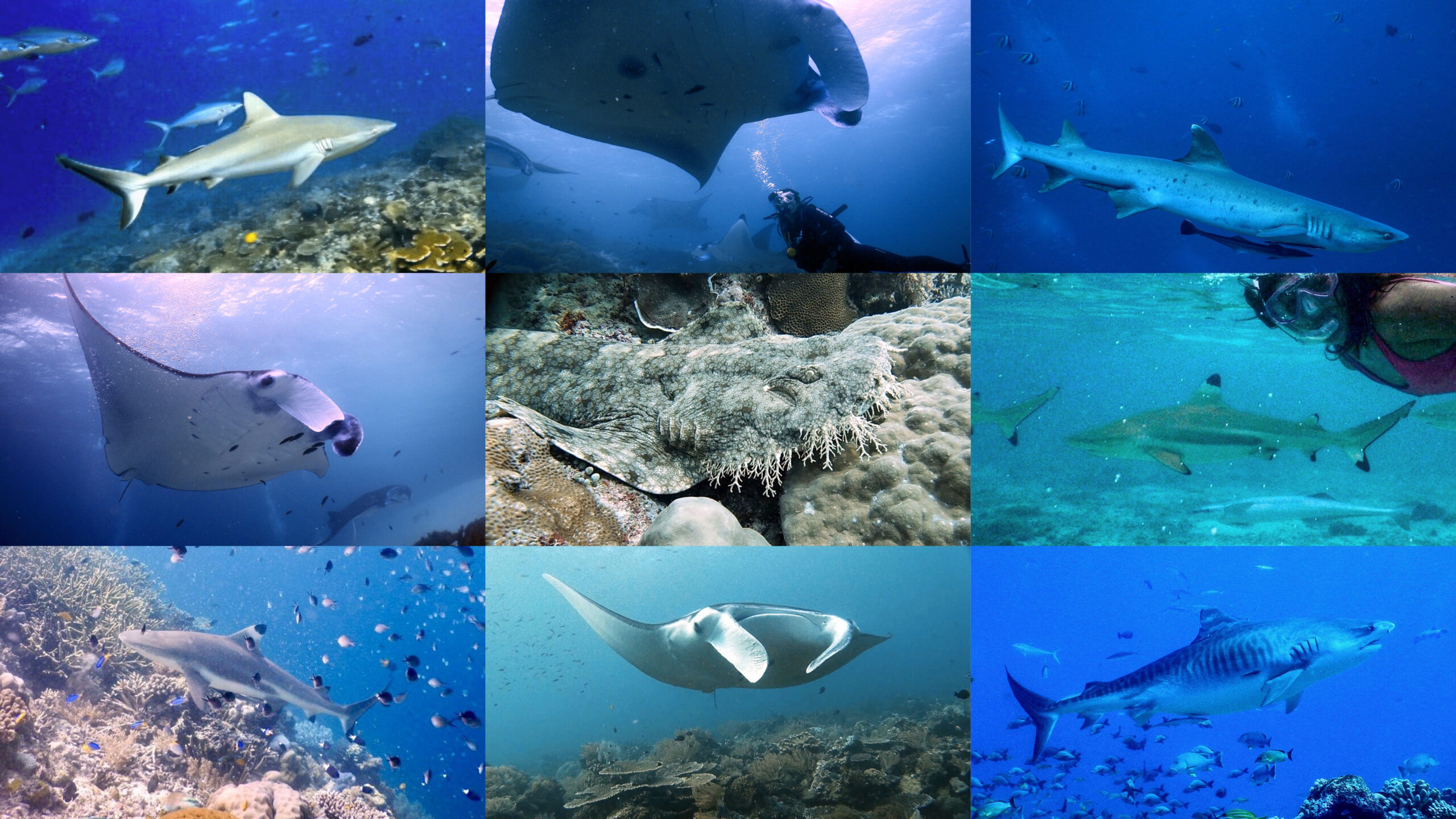

Photo © Hollie Booth

You may have heard that sharks are worth more alive than dead, and this is often true; people pay for the privilege of seeing sharks in their natural environment. So it’s often thought that ecotourism could provide an alternative livelihood to small-scale fishers who catch sharks. In some scenarios, this can work well, but it’s certainly not a case of ‘one size fits all’.

In Indonesia, the economic value of shark tourism is at least $22 million annually. The country is a global biodiversity hotspot and a top destination for scuba divers and shark lovers from around the world. However, it’s also the largest shark-fishing nation on the planet. People depend on the ocean in Indonesia and shark catches are of huge value – for food and financially. Shark conservation can have drastic consequences on these communities and ecotourism often isn’t a viable direct alternative.

Hollie Booth, a Save Our Seas Foundation project leader and recent PhD graduate, recognised this. She first became fascinated by small-scale fisheries and sharks while doing her Master’s, when she carried out a research project looking into the manta ray trade. Hollie found herself intrigued by the human aspect of the issue and has since been based in Indonesia, working at the interface between conservation and human welfare.

So, if ecotourism isn’t a direct alternative to catching sharks, what is? One potential solution is to pay small-scale fishers for pro-conservation behaviour (like releasing sharks) to compensate them for lost income. And here’s where tourism could come in: perhaps international tourists who come to see these animals could pay to support such community-based conservation. But would they be willing to, and how much money could be raised?

Photo © Hollie Booth

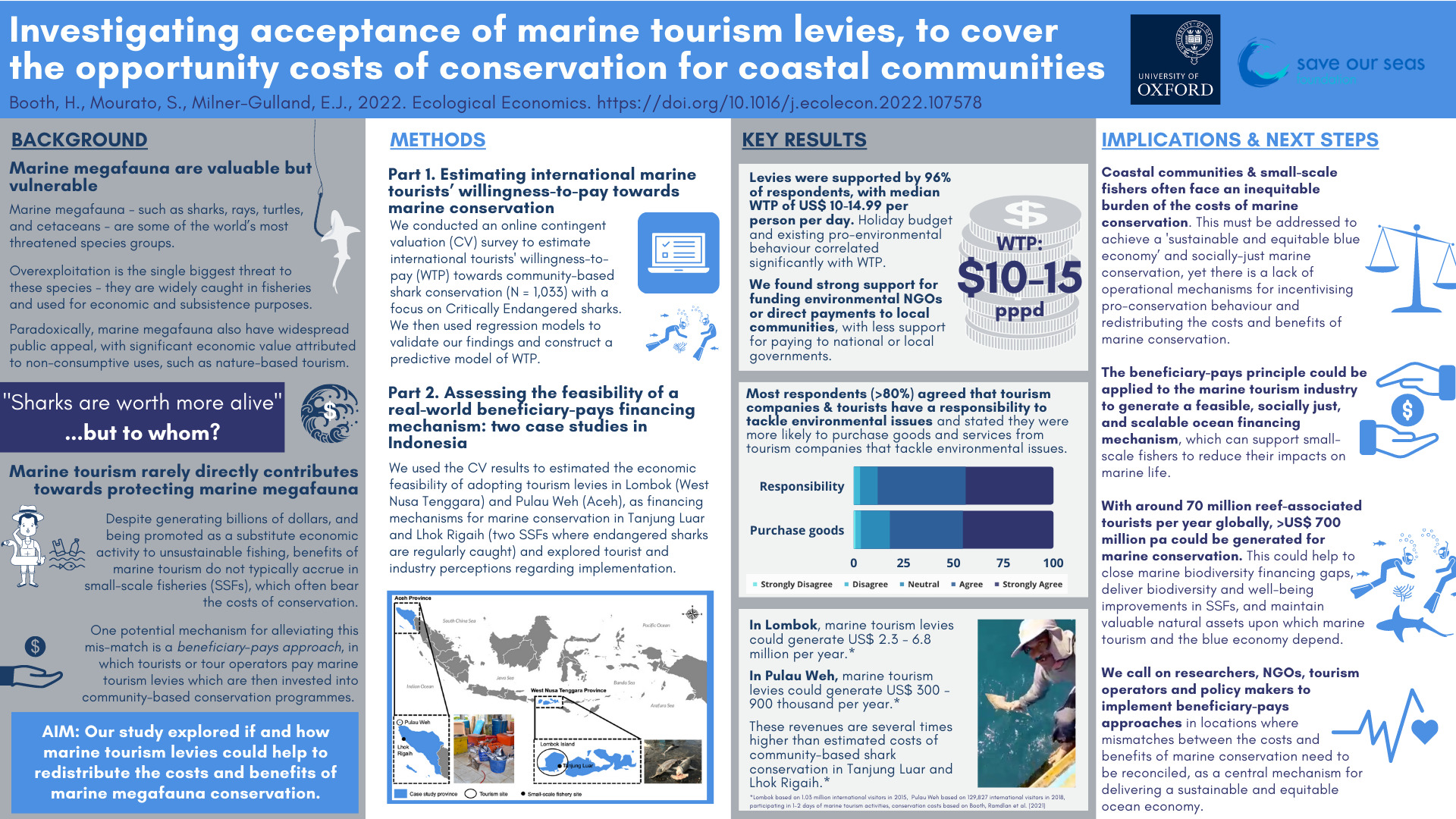

Hollie’s recent study, published in Ecological Economics, aimed to find out. How realistic would this be?

First, Hollie and her research team from the University of Oxford and the London School of Economics conducted an online survey targeting people with a general interest in travel. Participants were presented with a hypothetical scenario: they had taken a tropical beach holiday and were participating in a marine tourism activity. A small fishing village was close by, where endangered sharks are often caught for food and income. Participants were then asked how much they would be willing to pay to support conservation here by compensating fishers for reducing their catches of sharks.

Before they answered, some participants were shown a 60-second video about the threats facing sharks and the challenges of shark conservation in small-scale fisheries. Would this affect how much they’d be willing to pay?

In collaboration with Bogor Agricultural University, the team also spoke with marine tourism operators, fishers and tourists in two tourist destinations in Indonesia: Lombok Island and Pulau Weh. Both are close to small-scale fisheries, where Critically Endangered hammerhead sharks and wedgefish are regularly caught.

What did they find?

More than 1,000 people answered the online survey, of which 96% were in support of the scheme! Most people stated they would be willing to pay $10–15 per person, per day towards community-based shark conservation. Interestingly, watching the 60-second educational video seemed to have no effect on how much people were willing to pay.

‘I expected that those who saw the video might be willing to pay more, due to a better understanding of the issues or perhaps because they found the video and information emotive, but it didn’t have any significant effect,’ remarks Hollie. ‘This is interesting because it calls into question the effectiveness of education campaigns in terms of changing people’s behaviour and willingness to contribute to conservation.’

Photos © Hollie Booth

In Pulau Weh, tourist payments could bring in between $300,000 and $1.3-million each year. And in Lombok Island, which attracts larger numbers of tourists, between $2.3-million and $10-million could be generated. This is a lot, but is it enough to cover the costs of community-based conservation?

In short, yes! Based on other research conducted under Hollie’s SOSF grant, calculations showed that preventing landings and promoting the release of hammerhead sharks and wedgefish in the two nearby small-scale fisheries would cost, in total, a maximum of $236,000 per year. Tourist payments could raise at least 10 times this!

Paying fishers for pro-conservation actions in these fisheries could save more than 500 mature and 18,000 juvenile hammerhead sharks each year and 2,140 wedgefish annually, as well as other charismatic and endangered species like guitarfish and mobula rays. Currently, these fisheries are catching these animals both on purpose and accidentally, with a devastating effect on their populations.

‘I was pleasantly surprised by how much revenue could be generated – it’s pretty high and could raise really meaningful funding for community-based conservation,’ says Hollie. So what’s next for the research team?

‘We are currently trialling whether compensating fishers for live release will really work in these two small-scale fisheries. We have made an agreement with fishers that if they send us video evidence that they have safely released Critically Endangered species, we will compensate them for the amount of money they could have otherwise sold them for,’ she explains.

So far the results have been promising. A hammerhead shark, two guitarfish and 21 wedgefish have been safely released since the trial started four months ago. You can follow the project’s progress and watch the heart-warming live release videos here. The team hopes to establish some real tourist donation systems soon as a form of sustainable financing to cover the costs in the long term.

This is exciting news for the future of sustainable small-scale fisheries. Hollie’s research has shown how such schemes could be used across the marine tourism industry to generate a socially just and scalable ocean conservation mechanism that works for all. And it’s not just limited to shark fisheries – if there’s anything marine conservation needs, it’s money! Tourist-generated funds could be used to help fund marine protected areas, beach clean-ups, habitat restoration and much more.