Astonishing new insights into silky shark migrations

It’s unlikely that ‘Genie’, a jet-setting silky shark, knows anything about either the illustrious origin of her name or the headline-grabbing incredulity with which her travels have been met. She no doubt has her own ideas about where she’s heading and why. But for scientists sleuthing the secrets of where these animals move, the shark named for the late shark ecologist Dr Eugenie Clark has broken all the records.

‘I had a mixed gut feeling about the migratory nature of silkies from the Galápagos Marine Reserve,’ says Dr Pelayo Salinas de León, lead author of a new study on the longest migration ever recorded for a silky shark and co-principal investigator of the shark ecology project at the Charles Darwin Foundation. ‘While previous studies on pelagic sharks had revealed that they can travel for thousands of kilometres, our previous research on tiger sharks in the Galápagos had shown that they like to stay close to home due to the great abundance of food within the reserve. Since we always encounter silky sharks behind the boat during field work at Darwin and Wolf islands, I thought they might also like to stay close to home … only to be proved wrong big time!’

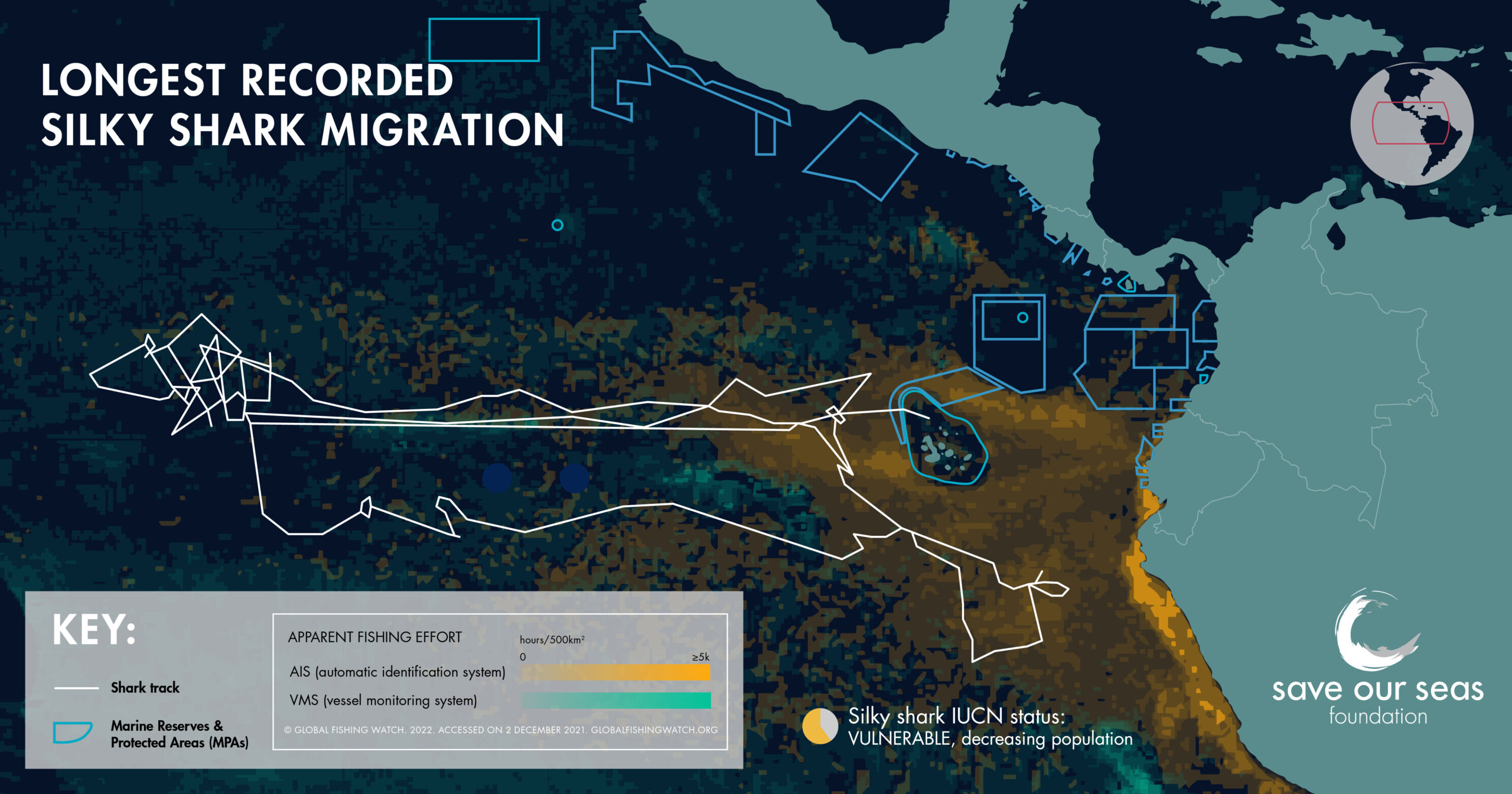

Genie was fitted with a fin-mount satellite tag off Wolf Island, in the north of the Galápagos Marine Reserve, in July 2021. What scientists then logged was an epic voyage: she clocked more than 27,666 kilometres (17,190 miles) of ocean travel in less than two years. ‘The record distance and repeated migration patterns displayed by this silky shark were surprising indeed,’ says Professor Mahmood Shivji, co-principal investigator of this research and director of the Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Research Center (SOSF-SRC) and Guy Harvey Research Institute, Nova Southeastern University. Professor Shivji is a co-author on the study that charts Genie’s journey, which was published this week in the Journal of Fish Biology. ‘Not only did this female shark travel massive distances west from the Galápagos to extremely far out into the open Pacific Ocean and then return all the way east but, remarkably, she then repeated this extensive migration westward to the same far away open ocean region using a strikingly similar travel pathway!’ As part of her vast voyaging, Genie swam halfway to Hawaii – twice. Genie was not simply racking up kilometres by speeding around sites close to ‘home’; rather, she ventured as much as 4,755 kilometres (2,955 miles) from the site where she was originally tagged. Her incredible swiftness and stamina aside, what has scientists astir is that her journey took her out of the protected waters of the Galápagos Marine Reserve and into busy international ocean space, where fishing effort is intense and the enforcement of regulations is low.

The tendency of silky sharks to associate with schools of tuna species and floating objects makes them especially vulnerable to industrial tuna fleets that fish around drifting fish aggregation devices. Photo © Matthew During

For Dr Salinas de León, this is important information that he needs in order to understand how the Galápagos Marine Reserve is protecting silky – and other wide-ranging – sharks. ‘The Galápagos Marine Reserve can be very effective in protecting near-shore ecosystems such as mangrove forests or coastal reefs and the species, such as corals or reef fishes, that reside within them. It can even protect highly migratory species, such as coastal sharks or pelagic sharks during part of their lives. However, the highly migratory nature of pelagic sharks means that sooner or later they will leave the reserve to follow their more basic instincts in their search for foraging areas, mates or birthing grounds. This highlights the need to combine the use of marine reserves and sustainable fisheries management around protected areas if we really want to save sharks from extinction.’

And while Genie’s swimming feat sounds remarkable, there is real cause for concern for her and her kin. The biggest threat to the silky shark is overfishing; after the blue shark, it is the second most commonly caught shark in global fisheries. Silky sharks are caught in both longline and purse-seine fisheries and they are particularly vulnerable to purse-seine fisheries that use fish aggregating devices, which are large floating objects that attract fish in the open ocean. ‘Our earlier studies revealed that fins from silky sharks made up the second highest proportion of fins by species in the international fin trade,’ explains Professor Shivji. ‘This strong market demand, coupled with intensive pelagic fishing in the Eastern Tropical Pacific and the clear ability of silky sharks to travel such huge distances offshore, makes it likely these sharks are crossing through heavily fished areas and are at great risk of either directed or incidental capture.’

There is, therefore, real urgency to these exciting findings. ‘Pelagic sharks in general are in big trouble mainly due to overfishing; more than 75% of these species are now threatened with extinction,’ says Dr Salinas de León. In fact, overfishing has caused silky shark populations to decline by 47–54% globally, but this percentage is higher (more than 90%) in some regions like the south-eastern Pacific. ‘If we want to save them, it is time to act.’ And certain conservation steps have already been taken: the silky shark is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List and has been listed on Appendix II of CITES to manage international trade in it. Dr Salinas de León stresses that the findings of this study add insight to a complicated conservation conundrum.

- Dr Pelayo Selinas de León

Researchers deploy a fin-mounted satellite tag on a silky shark to track her movements in almost real time, a procedure that is completed in around 5 minutes. Photo © Pelayo Salinas de León

The management of silky sharks needs nuance, and that requires an extensive understanding of how they live in the regions where they will be managed by specific conservation policies – or where their conservation will require international cooperation. ‘One of the main goals of the four collaborating partners in our large-scale study is to gain a solid understanding of silky shark migration patterns in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, including the overlap of silky shark movements with areas of intensive and largely unregulated industrial fishing,’ explains Professor Shivji.

‘Preventing further declines in already reduced pelagic shark populations is going to require bringing to light such information soon, if there is to be any hope of effecting changes in fishing practices.’

- Professor Mahmood Shivji

You would think that, having worked extensively on sharks in the Galápagos, Dr Salinas de León has seen it all. And yet, sharks like Genie manage to surprise him all the time. ‘To me it is mind-blowing that such a relatively small animal can clock an average travel distance of 50 kilometres (30 miles) per day for weeks or even months at a time!’ he exclaims. ‘This tells you how streamlined and energetically efficient it is.’ For him, these findings are simply the start of a host of other research priorities. ‘It also raises a lot of questions about why silkies undertake these great journeys,’ he muses. ‘Is it for food? For mating? To give birth? Or is it just to go for a stroll? We have a lot of work ahead of us to fully understand the amazing nature of these creatures.’

That work is a priority for both the Charles Darwin Foundation and its partners. ‘We have an extensive research programme on silky shark migrations in the Eastern Tropical Pacific region, with more than 100 silky sharks being tracked with satellite tags to get a proper understanding of the migration behaviour of this severely overfished species,’ explains Professor Shivji. ‘Obtaining shark tracks with good location resolution for over a year is difficult at best. In this case, we were able to track this shark for 18 months, which revealed an unexpectedly consistent migration pattern. This points to the need for long-term observations to understand fully the behaviour of pelagic shark movements. The scale of this work is made financially and logistically possible only because of terrific collaborative effort between four organisations: the Guy Harvey Research Institute and Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Research Center at Nova Southeastern University, USA, and the Charles Darwin Foundation and the Galápagos National Park Directorate in the Galápagos.’

Pelagic sharks are in deep trouble. Once a common sighting around the oceanic islands of the Eastern Tropical Pacific, large shivers of silky sharks are becoming rarer due to ongoing global population declines mainly from overfishing. Photo © Pelayo Salinas de León