Antarctica: A balancing act

As the last region on earth to be discovered by humankind, the importance of Antarctica now lies in its role in helping us to understand our changing world and find our future trajectory.

The historic urgency to find this southernmost continent was linked to the challenge of adventure and the prestige of human endurance. Today, research in Antarctica highlights the pace at which human beings can influence our planet and its processes. If anything, Antarctica is a reminder of our connectedness, and is symbolic of the balancing act needed to achieve sustainability. A challenging place where a united effort is needed to secure the ecological balance for our shared future, Antarctica is where humanity should be committed to getting it right.

Photo © Fiona M Jones | Penguin Watch

In 1969, television audiences tuned in to watch as the crew of Apollo 11 launched into space to complete the first moon landing. Accompanying the broadcast, the voice of an emerging British pop star called David Bowie rang out across the BBC airwaves with a plaintive hit that juxtaposed the palpable excitement of a voyage of discovery with a melancholy reminder of the adventure’s inevitable counterbalance – loneliness, danger and sacrifice. ‘Ground control to Major Tom … commencing countdown, engines on…’ A feverish sense of possibility gripped the world as the space race was finally ‘won’ by the American astronauts. Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’ sang instead of the pang of homesickness and feeling overwhelmed – and perhaps even the missed beauty of the earth as an imagined astronaut gazed back at our ocean home. Rather than basking in the glory of his achievement, Major Tom spins out of orbit with a resigned ‘Planet earth is blue … and there’s nothing I can do’.

In the very same year that Neil Armstrong took one small step for man on the moon, a collection of the first American female scientists made a giant leap for womankind as they disembarked on the continent of Antarctica. Their quiet achievement came after men had sailed the region since the 18th century as whalers and sealers, after explorers with names etched into polar history like Scott, Amundsen and Shackleton had ventured into the Antarctic interior in the early 20th century, and after male scientists had cemented their role on the continent. Of course, Western women had reached Antarctica in the years prior to 1969 (and oral accounts speak of women from Oceania centuries before), initially in name only as adventuring husbands gave regions of Antarctica their remote stamp, but in 1935 by physical footprint too, as Caroline Mikkelsen stepped onto what is believed to be the Antarctic Tryne Islands. Believed, of course, because Mikkelsen did not speak of her achievement for another 60 years. 1937 had seen another Norwegian explorer, Ingrid Christensen, and three other women be the first to land on the Antarctic mainland. But as scientists, women from Argentina, South Africa and the Soviet Union became the first to break ground in the region in the late 1950s, joining their male counterparts on the planet’s southernmost continent and the last-discovered region on earth.

If anything gives credence to the remote mystery and alien distance that Antarctica represents, it’s the idea that so many footprints are recent in our history of exploration and science. Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’ was an incongruous fit for the optimistic fanfare that accompanied the moon landing. His melancholy musings on the beauty of our planet and the human toll of endeavour could have been written instead to accompany the disembarkation of those groundbreaking American scientists, as Lois Jones, Kay Lindsey, Eileen McSavey and Terry Tickhill arrived in the same year on a continent with a landscape seemingly as lunar as that which the crew of the Eagle had encountered. For as long as human beings have been able to gaze into our skies, the moon has been within sight, if not within reach. But Antarctica was a place imagined in theory only until it appeared sketched onto maps in the 15th century as Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan (he of Magellan Strait fame) sailed ever-southwards on our spherical planet. Fabian von Bellinghausen first gazed towards an Antarctic ice shelf we now know as Queen Maud Land on 28 January 1820, but an error in the translation of his journals is purported to have left him uncredited in the history of the race to find Antarctica.

Photo © Matthew During

The hunt for Terra Australis

In most records, a land called Antarktos was the first imagined preserve of the ancient Greeks. This hypothesised great southern landmass was named quite literally as ‘the opposite of Arktos’, the Great Bear constellation that lights the northern hemisphere’s skies. This landmass, the Greeks asserted, would balance the landmass they knew in the northern hemisphere and comply with the symmetry of our earth’s spherical shape. Their idea would be proven correct nearly 1,500 years later, if only in the sense that such a landmass did exist. But while their theory of its existence and importance being linked to the balance it would bring in terms of physical landmass was inaccurate, it is fitting given what we now understand about Antarctica that these ancient ideas and names were centred on balance and connectedness. What happens in Antarctica – and what happens to it – are indeed connected to maintaining the balance of the rest of our planet. Perhaps not quite in the same way that the ancient academics first proposed it might, but it is certainly true that the fate of Antarctica affects us all.

Photo © Fiona M Jones | Penguin Watch

An era of discovery and a place of change

Today, Antarctica lies within reach – if not easy reach – of scientists and tourists alike. After the frenzy of the ‘race for the Antarctic’ began in about 1890 and nations battled to be the first to reach the South Pole, a period dubbed ‘the heroic age’ catapulted Roald Amundsen (Norway), Robert Falcon Scott (United Kingdom), Edward Adrian Wilson (UK) and Ernest Shackleton (Ireland) into the public imagination as they variously succeeded and failed in daring, dangerous – and in some cases deadly – attempts to claim achievements in polar exploration. The lure of Antarctica was not so much in our academic understanding of it, or in our respect for its ecological, oceanographic and climatological importance, but rather in what it represented for our human capacity for discovery – and conquest.

The undercurrent of global politics was perhaps the common thread running through each era that saw nations scrambling to lay claim to the continent and its waters and it was only some 27-odd years later that the battle for ownership of Antarctica took a scientific turn. In 1957, the International Geophysical Year (an attempt, apparently, to patch over Cold War divisions for the sake of global scientific advances) saw more than 50 research stations established in Antarctica by 12 countries: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Since 1957 the footprint of research across the region has increased and the arrival of tourism in the Southern Ocean has brought human beings closer to one of our last wilderness areas on the planet. The counterbalance to this increased traffic (which accompanies the footprint of fisheries that have persisted in the region for hundreds of years) is the knowledge and awareness that has been raised about how Antarctica functions. Polar science here shows us some of the starkest evidence for anthropogenic climate change and how it affects some of our planet’s ecosystems. It is here, at the poles, that we gain our understanding of melting ice sheets and glaciers (and their consequences for sea level rise). The collapse of the Larsen Ice Shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula’s east coast bordering the Weddell Sea was perhaps one of the most dramatic demonstrations of what average rising air temperatures mean over time. Scientists with different fields of expertise have been drawn to the region to document our changing world, from warming sea surface temperatures and changing currents to increased albedo (the reflection of solar energy off the earth’s surface into the warming atmosphere) across the blindingly white ice sheet that makes up about 98% of the Antarctic continent. And it is at the poles – the extremes at opposing ends of our planet – that our realisation of what balance truly means has the potential to shift most quickly.

Photo © Matthew During

Antarctic ecosystems and understanding change

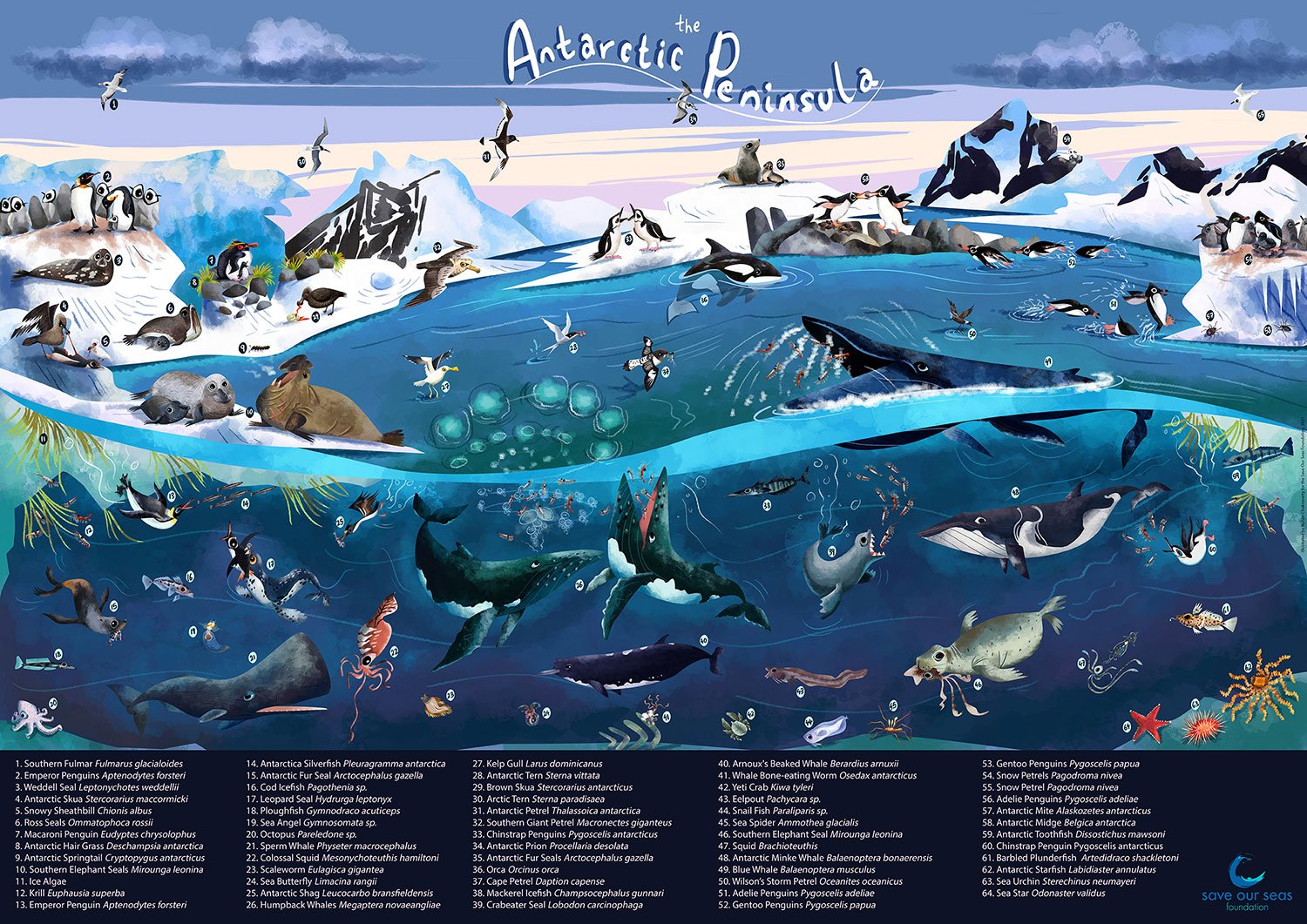

Dry, frozen and subject to extreme fluctuations in storms, winds and seasonal sunlight; it’s no wonder that the Antarctica we see as we flip through glossy coffee table books appears to us as a glittering desert of ice. On land, the skeletal remains of failed human endeavour endure in the form of old camps, and rusted wrecks like the whaling ship Governon play roost to Antarctic terns at Foyn Harbour. The Antarctic mainland is a harsh environment where any living organisms need to be extremophiles to survive – that is, adapted to the thick ice, sub-zero temperatures, almost non-existent rainfall and howling winds – and they are usually micro-organisms that we can’t see with the naked eye. However, if one circles around mainland Antarctica, the prominent reach of the Antarctic Peninsula pointing out into the Southern Ocean offers us an entirely different perspective. The coastline, the Peninsula and the dusting of subantarctic islands scattered around it in the Southern Ocean are rich in life. It’s the fine tapestry of climate, oceanography and biodiversity that are woven together here that reminds us of the more fitting reason why Antarctica – and its importance – are really about balance of the ecological kind.

Artwork by Rohan Chakravarty | © Save Our Seas Foundation.

The Antarctic underwater world is sometimes delineated by the flowing boundary of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) that encircles the continent at about 60° latitude. Although colder and saltier than the waters to its north, the Southern Ocean here moderates the climate somewhat compared to the harsh Antarctic continental interior. If one dives below the Southern Ocean’s surface and under the sea ice, the basis of life here is the same as everywhere on our planet: green plants, albeit microscopic, that harness the energy of the sun to produce their own food in a process called photosynthesis. A dizzying assortment of marine algae and phytoplankton species thrive here and are thrust nearer to the ocean’s surface (and the sun’s light) in a process called upwelling. Cold sea water dubbed Antarctic Bottom Water settles on the sea floor and in doing so forces warmer water to upwell towards the surface. These waters carry microscopic plants from the ocean’s inky depths higher into the water column, to where they can capture light energy. As they do so, they create one of the richest oceanic soups on our planet. Thanks to this process of Antarctic upwelling, the marine Antarctic food web is diverse: a nutritious oceanic grazing ground that underpins the array of animals thriving here, from microscopic crustaceans to fish, seals, whales and penguins.

Antarctica and its surrounding ocean seem almost too remote, too alien to have much to do with our lives elsewhere on the planet. However, the ice-covered continent and its waters that teem with life play a bigger role in regulating our global climate than we’d imagine. These oceanographic patterns – the circulations of various scales driven by the complex interaction of varying heat and salt content, strong winds, large waves and the formation and melting of ice – are an important element of the global ocean conveyor-belt system, and an element with connections to every other ocean basin on the planet. The ocean conveyor belt describes the circulation of currents around the earth that move cold and warm water between the sea floor and the surface, the poles and the equator. Antarctica and the Southern Ocean play a key role in moving heat from places that would otherwise get too hot to places that would otherwise get too cold. In a sense, the ancient Greeks were again correct in assuming that Antarktos was critical for the earth’s balance: their focus on land, however, missed the critical role of these southernmost masses of moving water that we now realise are another indicator of the true importance of this region and its function in achieving balance.

Photo © Matthew During

It’s not only climate: a history of biodiversity loss in Antarctica

The importance of Antarctica not only lies in helping us understand how we tackle the issue of climate change, but also speaks to the critical threat of biodiversity loss. In late 2019 the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) released a report outlining the link between the loss of biodiversity – that rich complexity of life that makes the earth so important in our known universe – and the loss of the ecosystem services that biodiversity provides us. That is, the myriad of jobs performed by every different plant and animal and fungus and bacterium on this planet is reduced each time a species flickers and disappears from our planetary inventory. This is of huge importance to human beings because these ecological jobs give us what we require to survive (oxygen, food, a habitable climate, life-saving medicines, jobs) and thrive (our cultures, spirituality, recreation and sense of belonging).

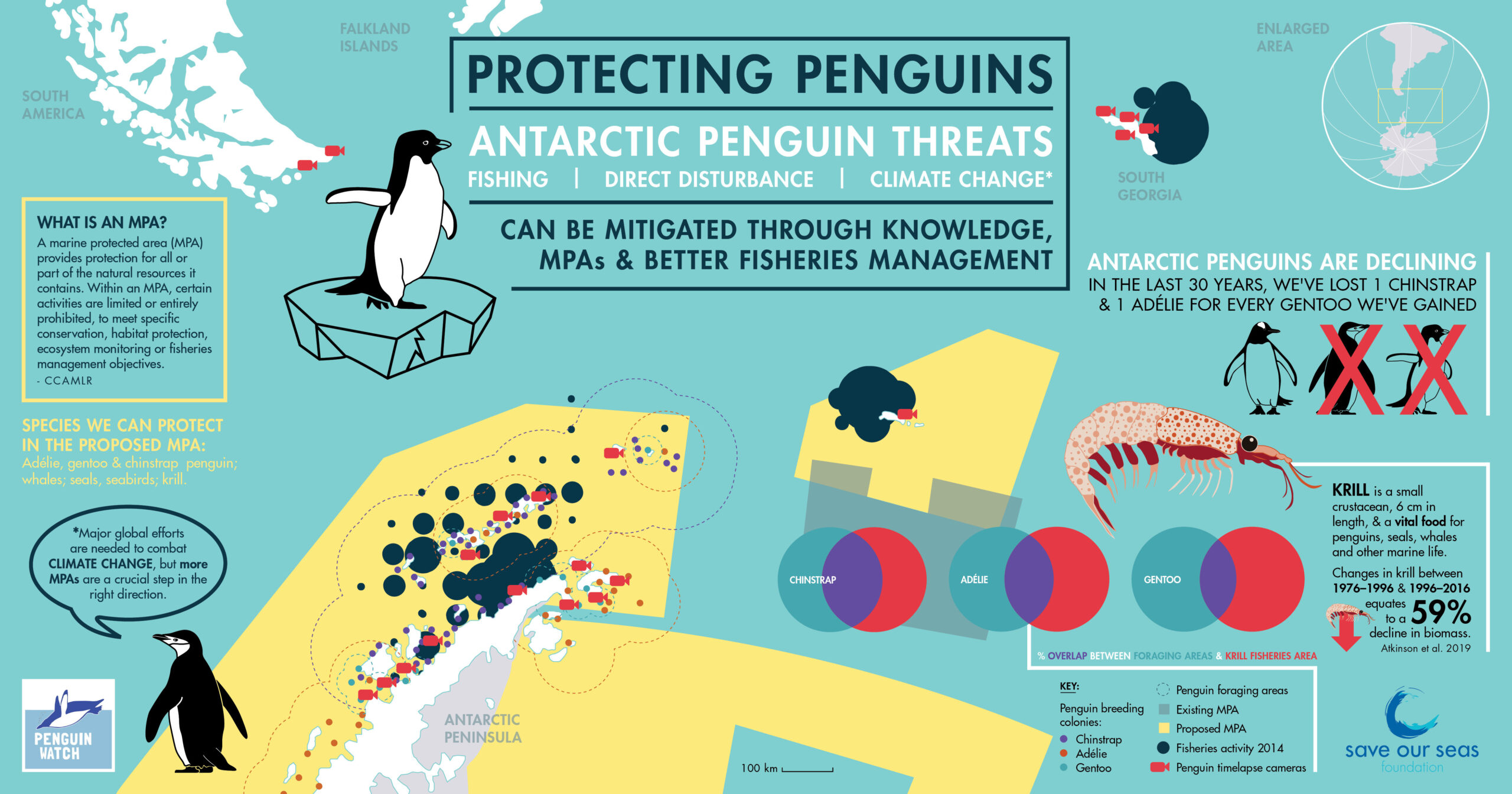

Disentangling the threats faced by Antarctica's penguin populations by looking at where colonies and feeding grounds overlap with possible threats. Artwork by Nicola Poulos | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Antarctica’s history with humans includes an extractive one, where whaling, sealing and fishing have seen nations race for more of what the region has to offer: biological resources. Sealing took historical tolls on elephant seals that were hunted for their oil and fur seals that were persecuted for their pelts. However, populations of both mammals have increased since the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals was signed in 1972. Similarly, whaling decimated populations of blue, fin, sei, humpback and sperm whales until a moratorium on all whaling activity was enacted by an agreement with the International Whaling Commission in 1982 and the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary was established. Yet scientific whaling persists in the region today (although indications show that the populations of many species of large whales are recovering), while commercial fishing has increased in effort after factory ships with on-board refrigeration and improved technology (a post-Second World War development) has allowed species like Antarctic cod, Antarctic toothfish and Patagonian toothfish to be harvested at scale.

But what of the key to the entire Antarctic food chain, that ignominious scurrying crustacean that swims in dense clouds in the waters surrounding the Antarctic Peninsula? Commercial krill fishing, although initially unpopular, has seen an upsurge since 2000 in response to our health-conscious obsession with omega-3 fatty acid supplements and the demand for krill products in aquaculture. Lacking the charisma of seals or the popular appeal of whales, the current Antarctic extraction crisis may in fact lie with the most important of all its marine characters: its krill. Declines in this ecological linchpin will have consequences that echo across the ecosystem.

Dr Tom Hart and his team looking over a penguin colony. Photo © Penguin Watch

The Antarctic Peninsula and its penguins

The Antarctic Peninsula is the continent’s most northerly extension and projects beyond the Antarctic Circle, which gives it the mildest climate on the continent. The result is stunning: colonies of Adélie, gentoo and chinstrap penguins can breed here and in snow-free months the rocks are coloured by lichens, mosses and algae. Antarctic hairgrass and pearlwort even bring flowering life to parts of the peninsula and the subantarctic islands in summer. Breeding pairs of south polar skuas, Antarctic (blue-eyed) shags and Cape petrels are among the 19 different seabird species that breed and nest in Antarctica, typically in large concentrations near the coast where a suitable climate and proximity to food make for optimal conditions. Below the frigid surface of the Southern Ocean around the Antarctic Peninsula, it’s the flitting, scurrying shapes of red-flecked, translucent crustaceans in their tiny millions that are the true stars of the peninsula’s delicate ecological show. Antarctic krill are the bedrock of Southern Ocean food webs, but their populations are not evenly distributed around Antarctica’s waters. In fact, more than 75% of the region’s krill is concentrated around the Antarctic Peninsula. This density of food brings huge populations of breeding seabirds, including penguins, as well as seals, whales and fish to the peninsula and the Scotia Arc (the island chain that extends from Isla de los Estados in the west to the South Georgia and South Sandwich islands in the east).

And it’s here at the Antarctic Peninsula that the implications of a number of competing human activities can be most clearly seen. The western peninsula holds the dubious record of being one of the world’s three sites where the greatest increases in local temperatures have been documented in the past 50 years. Declines in krill populations have raised alarm bells for ecologists who then try to track the ramifications across the Antarctic food web. For many scientists, the population numbers and breeding distribution of the seabirds that abound across the Antarctic Peninsula and the islands in the Scotia Arc are the most logical indicators of how both local and global threats are affecting biodiversity. Research indicates that penguin numbers on the Antarctic Peninsula are in decline; but given the host of different threats that all collide in this region, the question remains – why? Around the world, seabirds of all kinds face similar threats to what we witness in the Antarctic: pollution, climate change, fishing and human presence act at local and global scales, with slightly different implications across regions. If we can understand their impacts on seabirds in Antarctica, perhaps there will be lessons learned that are valuable elsewhere.

On the Antarctic Peninsula, the site of densest human presence in all of Antarctica, the overlap between local threats like commercial fishing activity, scientific research and tourism – and the global-scale threats of pollution and climate change – makes for a complicated but fascinating scientific challenge. To answer the question of which of these threats is making the biggest impact on plummeting penguin numbers, a new era of endeavour and boundary pushing has entered the Antarctic picture. The scale and scope of research on marine predators – and on penguins in particular – has been increased by ambitious, out-of-the-box projects like Penguin Watch, Seal Watch and Seabird Watch, run by Dr Tom Hart from the University of Oxford together with a host of collaborators and colleagues.

Dr Tom Hart in the field. Photo © Thomas Peschak

Restoring the balance: Antarktos and the future

The Antarctic Peninsula may have no permanent human and industrial development, but the density of research bases here is the highest on the continent. Competing claims from the United Kingdom, Argentina and Chile are held at bay, with no single country claiming sovereignty, as a result of the Antarctic Treaty. Signed in 1959, this agreement and its associated documents ban military activity, promote scientific activity and freedom, and regulate human activity on and claims to Antarctica. But as tourist activity increases, and commercial fishing continues, and our climate changes all the while in the background, the future of the phenomenal ecosystem that is the Southern Ocean around the Scotia Arc – and the Antarctic Peninsula in particular – becomes ever-more fragile. While the Antarctic Treaty may help to govern activity on the continent, it lacks the political teeth to regulate all activity, especially biological extraction, at sea. One tool that conservationists use to help mitigate declines in marine populations is marine protected areas and Antarctica has two in the form of the Ross Sea Region Marine Protected Area and the South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf Marine Protected Area. Other significant marine protected areas have been declared across some subantarctic islands, notably the South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands Marine Protected Area in the Scotia Arc. But what of the peninsula itself, this site where rich Antarctic biodiversity and its threats collide, where the density and operation of both is highest across the region?

It is here that Bowie’s lyrics are hopefully proven wrong, their melancholy something to rouse the age-old sense of challenge that Antarctica seems to provoke in us rather than to describe the isolation at one of the most remote regions on earth. ‘Planet earth is blue … and there’s nothing I can do…’ If there is anything that Antarctica can show us, it’s that persistence pays off. Endeavour can push us to test traditional limits and push the bounds of what we believe is possible. The history of Antarctica may be littered with failure and struggle, but there are equally small gains whose significance we may only notice decades later. The ancient Greeks might have been wrong about why Antarctica is important, but they were certainly right in that it is important.

At some of the most remote reaches of our planet, the link between space and sea becomes clear: if we can harness the power of technology and pair it with the tenacity of human determination, we may yet have a chance to interpret the past, measure the present and plan for the future. And underpinning it all is perhaps the sense of humility that we sense from Major Tom as he stares back at the wonder of the earth: as we gaze at one of the last wildernesses on our planet, we might know that our planet earth is indeed blue, and that there is much we can do to secure its future.