A family affair

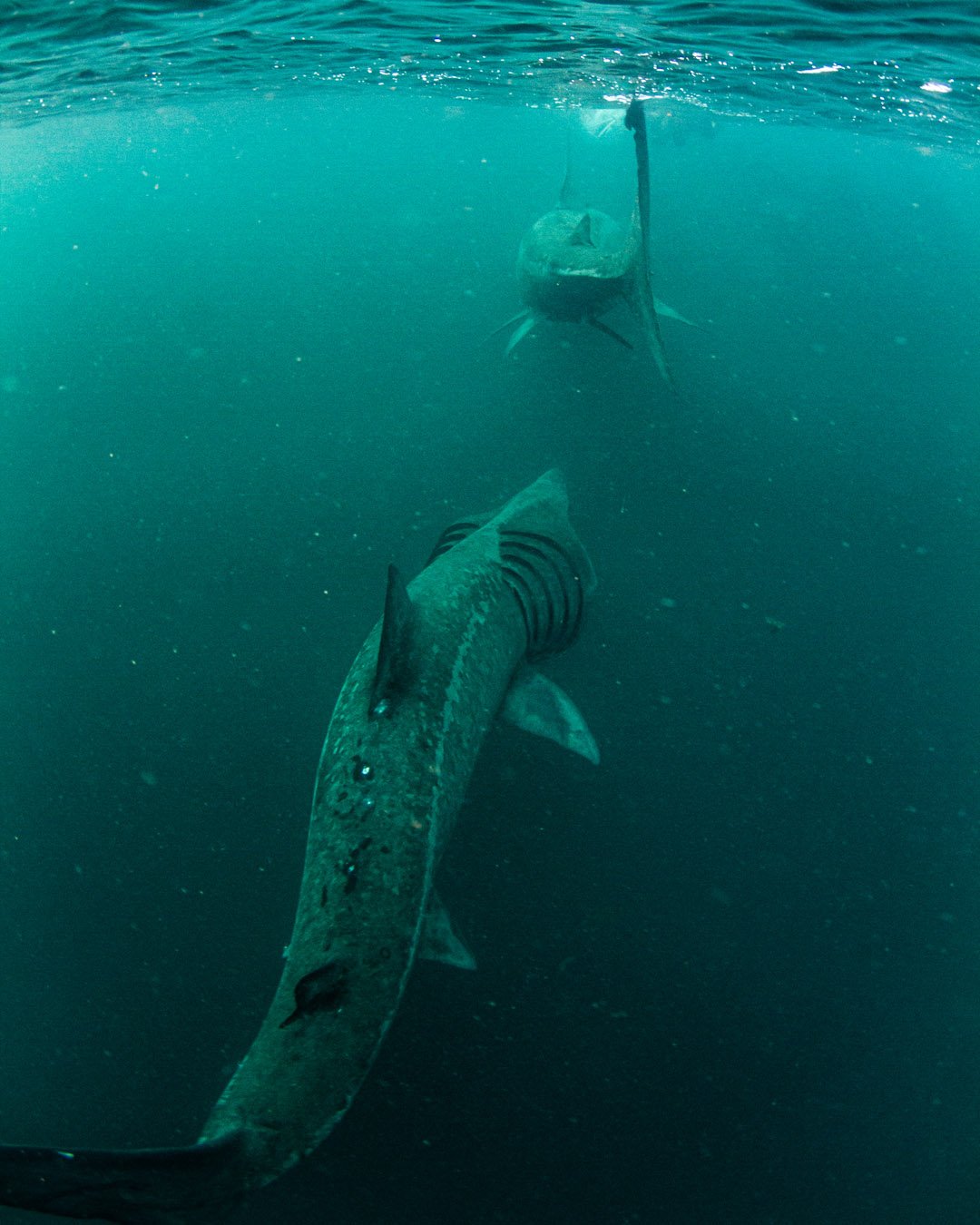

Evidence of social connections in basking shark behaviour?

Basking sharks, the second-largest sharks in our seas, continue to amaze scientists as we learn more about their lives. These enormous, filter-feeding sharks made headlines in 2018 for their ability to breach clear of the water’s surface, making acrobatic leaps thought only possible from predators like white sharks.

And these secretive sharks have surprised us again in 2020. Considered a cosmopolitan species that is found worldwide, scientists have previously recorded basking sharks migrating thousands of kilometres across the ocean. They also knew that many sharks returned to aggregate (sometimes in their hundreds) at known feeding grounds each year. This kind of behaviour, where animals repeatedly return to particular sites after large-scale migrations, influences how their populations are structured. But what is the genetic consequence of this behaviour in basking sharks? Do different populations mix? Is there interbreeding (and therefore, genetic exchange) between basking sharks in different areas? What are the chances that the same sharks meet one another again each season, and could they be related?

As it turns out, there is a structure to the genetics of basking shark populations that group together seasonally in the North-East Atlantic Ocean (NEAO) near Ireland and Scotland. And basking sharks seem to hang out in related groups when they do aggregate to feed. Basking sharks may therefore not only move faster and with more agility than we previously thought, but have more to their social lives than we have known before.

Scientist Lilian Lieber from the University of Aberdeen and her co-authors found that basking sharks return to favoured feeding areas in the Irish Sea and Scottish Sea of Hebrides. Their paper, Spatio-temporal genetic tagging of a cosmopolitan planktivorous shark provides insight to gene flow, temporal variation and site-specific re-encounters, was published earlier this year in Scientific Reports. Their results highlight the Irish Sea as a critical oceanic corridor for basking sharks. It appears these sharks migrate through this area, marking it as a passage they frequently use that makes conservation sense to manage. Not only were these sharks returning to aggregate at favourite feeding sites, but some of these groupings tended to be more related to each other than to other sharks in the wider NEAO population.

Photo © James Lea

One of the co-authors on this paper was Professor Mahmood Shivji, Director of the Save Our Seas Shark Research Center and Guy Harvey Research Institute, Nova Southeastern University. We spoke to Professor Shivji, a conservation geneticist, to help us understand what new insights genetics has brought us about basking sharks.

We need to know about how, and where, sharks move so that we can protect them appropriately. But why use genetics? How does this improve what we would otherwise know from mark-recapture and satellite tagging methods?

Mark-recapture methods (tagging a shark with a “spaghetti” information tag, and later potentially recapturing it to see where it has moved) frequently do not provide accurate knowledge of shark movements because information about an individual shark’s travels in-between the mark and recapture positions is unknown. That is, the shark could have moved long distances in-between where it was first tagged and where it was eventually caught. However, if it migrated back to close to its original tagging site where it was recaptured, it would provide an erroneous estimate of the actual distance the shark had travelled (a much shorter distances than in reality, meaning that we underestimate distance!)

Satellite tagging provides a direct view of the movements of a shark after it is tagged and released, but is limited to inferring short-term movements over time because the tag batteries run out or because the tags (especially in the case of pop-up satellite tags as used on basking sharks) frequently detach prematurely from the shark. As a result, movements are typically revealed over a limited period of only three to 12 months. Additionally, physical movements alone as derived from satellite tags do not provide information on whether the sharks are mating when they move to a different location.

Genetic analysis, although giving an indirect measure of movements, reveals whether gene flow (mating) is occurring between different areas. This presence or absence of gene flow information is essential to identify if genetically different populations exist to target conservation efforts to protect genetic diversity. Modern genetic and genomics analysis also provides a long-term view of movements and gene flow over the timescale of a few generations. Combining satellite tagging and genetic methods offers the best view of shark movements, gene flow, and population identification.

Photo © Luke Saddler

Basking sharks are extraordinary creatures, but they are not on our radars as often as, say, white sharks. What prompted this research, and what makes understanding basking sharks so crucial to conservation?

Basking sharks are assessed as Vulnerable to extinction by the IUCN Red List, and there are substantial concerns that their abundance is declining globally due to accidental catch in fishing gear and deteriorating ocean ecosystems. As a rule, conservation strategies for wildlife, including basking sharks, are most effective when based on a robust understanding of the basic biology of the species in question. Unfortunately, knowledge of basking shark biology is minimal, partly because of the difficulty of encountering this species, and partly because studying a large, highly migratory species in a vast ocean is logistically complicated. Our study was undertaken to add to the basic biology of this species by contributing a perspective obtained from a genetics approach.

Photo © James Lea

Is there anything you think that policymakers, government, or conservation decision-makers should be taking note of from this study?

This study has raised the potential of genetically differentiated populations existing within the North East Atlantic – an unexpected revelation. This potential should be confirmed using higher resolution genome-scale markers and methods. The study also suggests the Irish Sea is an important transit corridor for basking sharks, making it a critical geographic focus for decision-makers to manage human activities in this area to protect basking sharks as they migrate through here.

And what about our readers? What one thing would you most hope they took away from the new insights this paper gives us into the lives of basking sharks?

A particularly interesting finding about the lives of basking sharks revealed by the genetic analysis was that the individuals in some aggregations were more closely related to each other than to the rest of the broader population. The existence of kin groups raises the intriguing possibility that there may be some social interaction in these animals, including travelling together. This was an unexpected finding for a species where individuals were previously thought to lead completely independent lives.

As scientists continue to scratch at the surface of the complex lives of these animals, we must connect these two ideas: the role sharks play in the healthy functioning of our oceans, and our responsibility to protect them – for their intrinsic right, and our survival. It seems hard to connect to sharks in a way with which we can identify. But we can understand, and perhaps even identify with, family groups and hanging out with people we know. So perhaps as basking sharks continue to surprise us, we will learn to see more in these creatures than their impressive size and gaping mouths that sieve tiny, planktonic plants and animals from the cold, dark waters of their ocean home.

Photo © James Lea

Reference: Lieber L, Hall G, Hall J, Berrow S, Johnston E, Gubili C, Sarginson J, Francis M, Duffy C, Wintner SP, Doherty PD, Godley BJ, Hawkes LA, Witt MJ, Henderson SM, de Sabata E, Shivji MS, Dawson DA, Sims DW, Jones CS, Noble LR. 2020. Spatio-temporal genetic tagging of a cosmopolitan planktivorous shark provides insight to gene flow, temporal variation and site-specific re-encounters. Scientific reports, 10(1), pp.1-17.

Read the paper here.