The ghosts of sawfish past

I never thought that working in a museum for a few days would inspire me. The quiet, ordered presentation of the natural world in a setting locked away from the elements has always lacked what I love most about research and wildlife: being outside in wild places, the excitement of searching for and eventually seeing live animals, and documenting those experiences. Field work is, for me, the most meaningful part of biological research because it is a process of discovery: of the natural behaviour of animals; of the ways in which the fate of animals, habitats and human communities are linked; and of my own strengths and limitations.

But sitting in the basement of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge, I became immersed in a different type of discovery. It was like opening a dusty volume filled with long-lost stories of expeditions in West Africa. Not from hundreds of years ago, but from a different era in terms of sawfish populations nonetheless: the 1970s. What a difference 40 years can make.

In 1974 and 1975, Dr Nigel Downing conducted a study of sawfishes in the Casamance and Gambia rivers in Senegal and The Gambia respectively. He worked in collaboration with local fishermen, asking them to bring him any sawfishes they caught. Back then sawfishes were no more than a nuisance to local fishers; they got entangled in their fishing nets and damaged them and they had little value at market. The fishermen caught a great many sawfishes, especially during the rainy season when there was clearly an abundance of sawfish pups in both rivers. They usually kept only the sawfishes’ saws, also known as rostra, and sent the meat to Ghana where dried shark and ray meat was – and still is – popular. When Downing’s project was brought to an abrupt close, he was able to bring more than 40 sawfish rostra back to Cambridge, where they lay unnoticed – until now.

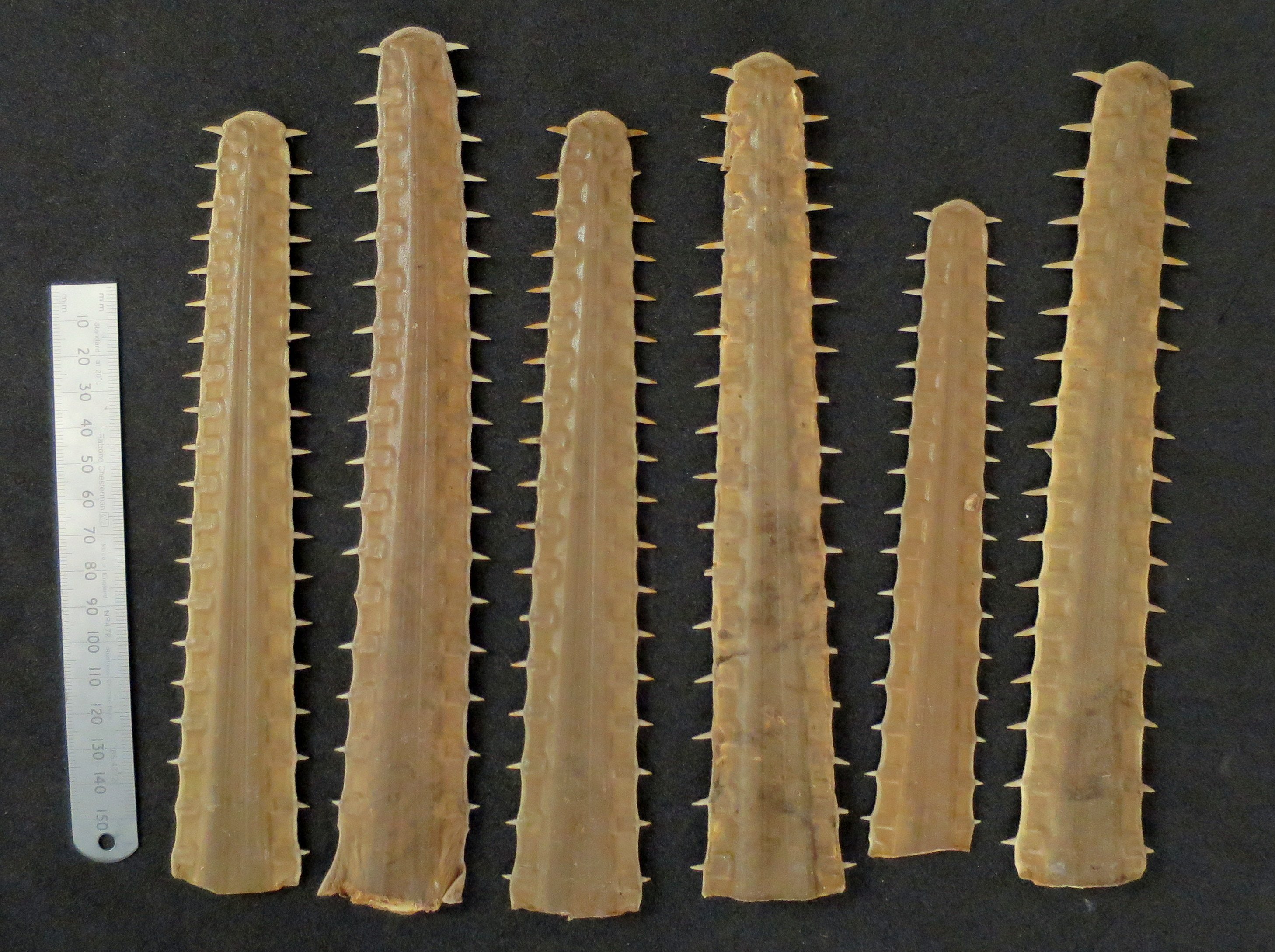

A handful of saws from young largetooth sawfish Pristis pristis collected from The Gambia River in 1974. © Photo by Ruth H. Leeney

Before me were four wooden drawers holding carefully wrapped layers of tissue paper, which I folded back to reveal bundles of rostra from very young sawfishes. I have never seen so many sawfish rostra all together in one place. On some the skin still shone golden, while others were encrusted with river mud or bore a solitary, glittering fish scale impaled on a needle-sharp tooth. They seemed like a collection of care-worn Christmas decorations. In these museum drawers lie the relics of a time when sawfish saws could be collected by the handful and were worn on the headdresses of the Bijago people of Guinea-Bissau or placed on the roofs of houses in The Gambia and Senegal to protect families from evil spirits. Nature’s most decadently decorated animals, and the traditions they inspired, are now only fading memories in West African societies.

In the stillness of the museum’s basement, where all is clean, carefully stored and climate-controlled, I felt a million miles from the dust, mud, burning sun, clamour and stench of fish markets and the general sensory overload that comes with my usual work in Africa. But as I eyed the museum treasures, I was transported to a different West Africa: one where rivers teemed with sawfish pups. Fishermen in Guinea-Bissau had described to me how, years ago, they went to the beach at night and speared small sawfishes in the shallows by the light of their torch flames. Holding the miniature saws of young sawfish in my hands, I imagined and wondered at such a scene of abundance – a scene that exists no more.

Nonetheless, these ‘ghosts of sawfish past’ can reveal stories never before documented. Although sawfishes disappeared from much of West Africa several decades ago (we’re still not sure where – if anywhere – they remain in West Africa), the collection at Cambridge can tell us much. Which species lived in The Gambia and which in the Casamance River? Were they closely related to the sawfishes found on the other side of the Atlantic, in Florida, The Bahamas, or were they different? Did sawfishes from these two rivers move large distances along the West African coastline, or did they stay close to the places where they were born?

Genetic analysis of the dried cartilage from sawfish saws is now possible and will answer some of these questions. It may also help researchers to understand whether sawfish populations are able to recover in West Africa or if, once gone, they are gone forever. I’ll soon be heading back to the mangroves and coasts to continue my search for Africa’s last sawfishes, but with a new respect for the invaluable role museums can play in providing a window to the past. Knowing what has been lost in West Africa, can we redouble our efforts to protect the sawfish populations that remain, before they meet a similar fate?

Many thanks to Matt Lowe, Collections Manager of University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge, for facilitating access to the collection and to the SOSF for funding the research visit. Ruth Leeney is funded under award NA15NMF4690193 from NOAA Fisheries Headquarters Program Office, the US Department of Commerce, the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation and the Wildlife Conservation Society.