Shark skin time travel

Erin uses fossilised shark scales to go back in time to the world of sharks before humans, giving us our first real glimpse of what pristine shark abundance might have looked like.

My avid fascination with the ocean started at a young age. From my earliest memories of snorkelling I know I was captivated by the intricate beauty, elusiveness and complexity of marine ecosystems, and I have naturally been drawn to sharks as a manifestation of these traits.

While studying abroad and doing research in Australia, Palau and the Northern Line Islands during college, I experienced the unspoiled splendour of protected reef ecosystems and observed at first hand the impact of destructive human activities on them. I realised that I didn’t want to study coral reef ecology or sharks just for the sake...

Reconstructing mid-Holocene shark baselines in Panama and the Dominican Republic using dermal denticle assemblages

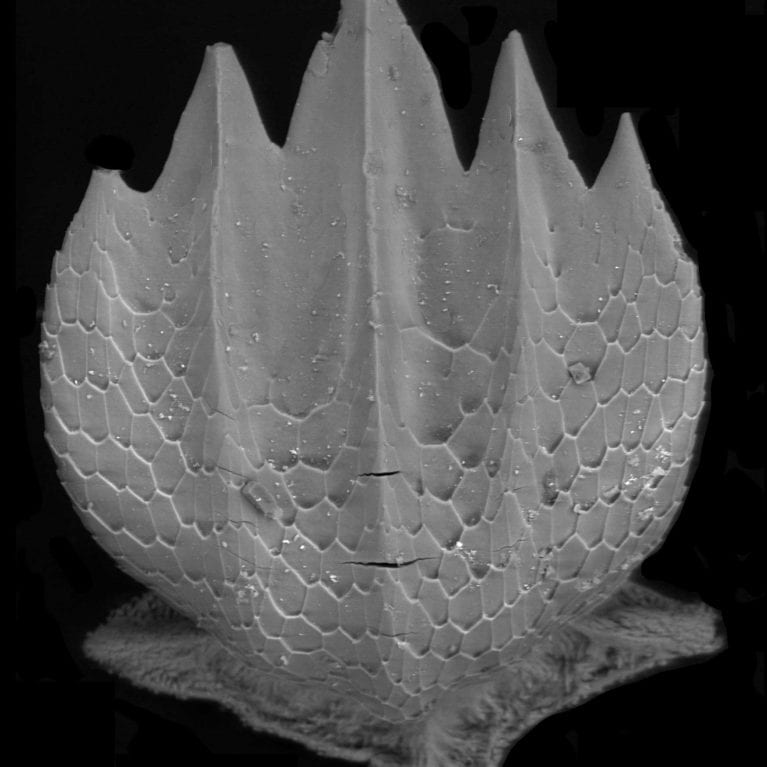

The key objective of this project is to identify shifting baselines for Caribbean shark populations and inform local shark conservation targets in Bocas del Toro, Panama, and the Dominican Republic based on historical trajectories of population degradation. Furthermore, this project aims to confirm the efficacy of using fossilised dermal denticles to quantify shark populations in the past.

Establishing baseline conditions for shark populations is central to understanding how humans have altered shark abundance, species diversity and distribution over time, and can thus influence their conservation status as well as inform management practices by placing current ecosystem changes into historical context. This is particularly crucial given that sharks are extremely vulnerable to overexploitation due to their life histories. Predation by sharks plays an important top-down role in structuring prey populations, which can resonate throughout the reef community given its high degree of connectivity. Selectively removing large predatory animals from the food web can thus impact the health and resiliency of the entire ecosystem. However, how can we effectively restore shark populations if we don’t know what constitutes a pristine population? Ultimately, as anthropogenic activities continue to devastate reefs, it becomes increasingly important that rigorous baselines are used to define conservation priorities and encourage more precautionary management.

Over the course of human history, fishing has had an enormous influence on the health of marine ecosystems, particularly in the Caribbean, where phase shifts and reef degradation are more pronounced. While modern ecological studies offer insight into the ramifications of the removal of predators on the trophic structure, diversity, health and resilience of reef communities across gradients of human exploitation, no pristine coral reef ecosystems remain today. Historical records from prior to the rise of modern-day fishing practices can paint a picture of coral reef community size and diversity, but are criticised for being anecdotal and limited in time frame and scope.

Undoubtedly, artisanal fishing in the Caribbean before the 1950s significantly altered the community composition of reef ecosystems and even generated signs of over-harvesting, invalidating baseline estimates that rely solely on modern survey data. While some shark populations have been documented to have declined by as much as 90% since the 1950s, pre-industrial historical data for many species is absent, leading to inaccurate estimates of stock depletion as well as distorted perceptions of baseline conditions. This perpetuates the ‘shifting baseline syndrome’, an insidious phenomenon derived from the gradual drift in generational collective memory regarding the definition of ‘pristine’.

However, to quantify degradation over the entire timeline of human interaction with sharks, paleontological data must be used given that only the fossil record can provide pre-human baselines. Previous studies of this nature have largely been restricted to corals, and no accurate baselines for shark assemblages in the Caribbean currently exist.

The aims and objectives of this project are to:

- Evaluate mid-Holocene abundances of sharks to establish pre-human baselines.

- Characterise the amount of natural variation in shark assemblages on modern reefs and determine the impact of sub-recent fishing activities on shark abundances.

- Determine the taxonomic composition of pre-human and sub-recent shark assemblages and assess any shifts.

- Initiate educational outreach activities in local communities in order to instil the importance of shark conservation.