Where do our eagles fly?

Understanding the movement behaviour of South Africa’s

Critically Endangered common eagle rays

The common eagle ray is one of the latest to join the growing list of Critically Endangered shark and ray species globally, as classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. The unfortunate classification means that the species should be considered a priority for conservation and management. As Sir David Attenborough has stated, ‘The IUCN Red List tells us where we ought to be concerned and where the urgent needs are to do something to prevent the despoliation of this world. It is a great agenda for the work of conservationists.’ As such, it is important that we revisit what it is we know about this species and what research we can and need to undertake.

Myliobatids (eagle, devil and manta rays) are charismatic fishes and have become popular species with both divers and fishermen across much of their distribution. They have also been increasingly recorded as migratory fishes, with characteristic aggregations of thousands of individuals effortlessly ‘flying’ through the water column. These aggregations are indeed majestic but are also likely linked with important life history events, including feeding or reproduction. Importantly, as with all fishes, aggregations can render species vulnerable to human exploitation, as they concentrate themselves within areas where they may be more readily caught. This behaviour, linked with limited biological productivity (females produce only a handful of pups per litter), has rendered many myliobatids vulnerable to large population declines. As a result, many species demonstrate decreasing population trends and have been listed as Vulnerable or Endangered by the IUCN.

Dr Amber-Robyn Childs surgically implants an acoustic transmitter into a common eagle ray. Photo © Acoustic Tracking Array Platform

The common eagle ray is arguably the worst affected of all Myliobatids globally, as indicated by its recent demotion to the dreaded status of Critically Endangered. The species is widespread throughout the eastern Atlantic, stretching up the west coast of Africa and across the Mediterranean Sea. However, it has largely vanished from catch and trawl reports in much of its northern distribution – where it was once prolific. Several reports of large aggregations of common eagle rays in the Mediterranean exist, while this behaviour is thought to have contributed towards population declines via local trawl and gillnet fisheries. The species is estimated to have undergone a population decline of more than 80% globally!

In contrast to the global situation, South African common eagle rays are considered to be decreasing but stable, with stocks that are not considered to be under any major threat of extinction. Additionally, direct threats to the species via fisheries pressure are considerably lower than in the northern parts of the species distribution. As such, the region could be considered a major stronghold for the species at large and a prioritised area for research and conservation.

In South Africa specifically, however, many data gaps for this species remain, making effective management very challenging. A poor understanding of the species movement behaviour is at the forefront of this lack of knowledge. Scientists know that the species is more often caught by recreational shore anglers in certain areas and at specific times of the year. This suggests some degree of movement along the coast, although it is not understood where the fish move to when they do so and why.

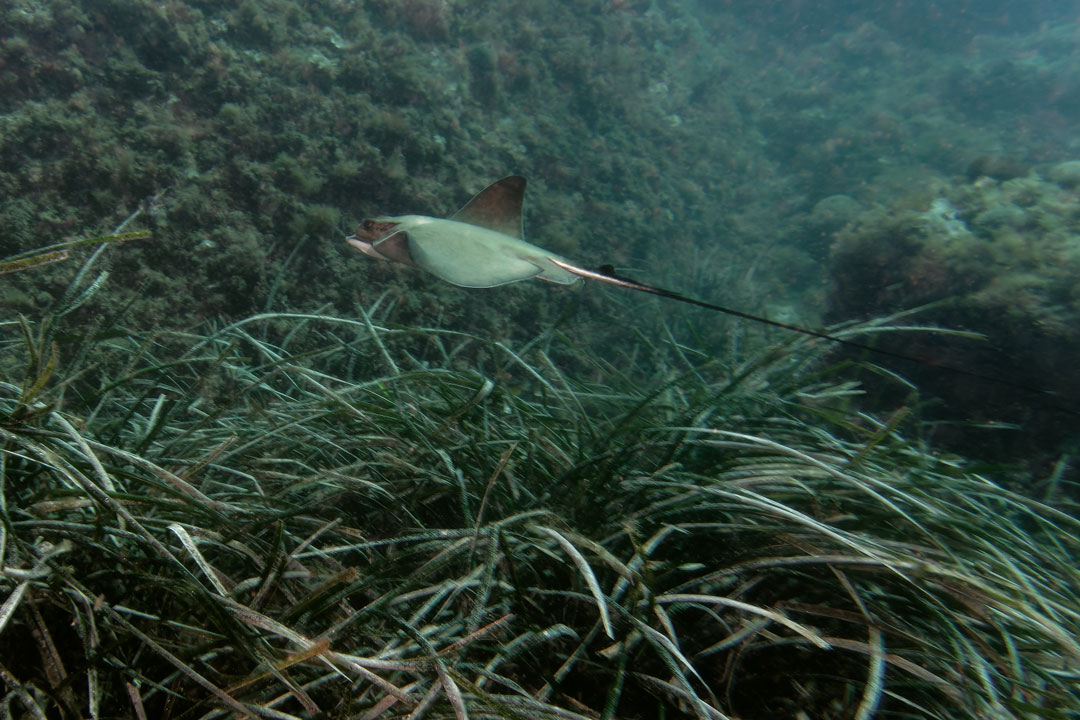

A common eagle ray swimming through Mediterranean waters. Photo © Labetaa Andre | Shutterstock

Understanding the levels of residency, the extent of coastline used, and aspects of migratory behaviour would provide valuable information for assessing current management measures and informing additional ones where necessary. For example, on the broadest scale, it is important to understand whether the eagle rays, which are frequently encountered within South African waters, remain here throughout their lives or whether they might cross our borders and venture into other countries, where they may be less protected. On finer scales, spatial data can inform whether Marine Protected Areas (MPAs, spatial protection) could provide (or are providing) protection for this critically endangered species. Understanding and identifying migratory behaviours, including potential large aggregations, might also inform important seasonal closures and protection. Already, there has been some anecdotal evidence to support aggregation events in South African waters, in places such as Storm’s River mouth and Langebaan Lagoon.

The general lack of movement information presents a major bottleneck to the improved management and conservation of this critically endangered species. Considering the extensive Acoustic Tracking Array Platform (ATAP) array of telemetry receivers along South Africa’s south and east coasts and the predominantly inshore distribution of this species, acoustic telemetry was chosen as an ideal study method. Using this method, transmitter tags, inserted into the abdominal cavity of fish, emit unique signals detected by moored receivers along the coast. Because each detection has a time stamp, scientists can collect continuous spatial and temporal movement data from tagged fish.

A recently caught eagle ray awaits acoustic transmitter implantation. Photo © Acoustic Tracking Platform

The research team has successfully tagged 13 common eagle rays from the Port Alfred area of the Eastern Cape. These fish have been collecting critical data over the past 18 months and will continue to do so until February 2024. In addition to the extensive ATAP array, several dedicated receivers have been placed inshore within the immediate area where the fish were captured. This will provide scientists with finer-scale movement data while the fish remain within that area and can provide an indication of the frequency and amount of movement happening between inshore and offshore environments.

The project hopes to grow larger by tagging additional animals as it will expand into other locations throughout the country, including the Western Cape. Funding is currently being sought to help facilitate this expansion through the purchase of additional transmitters. Simultaneously, we eagerly await the first set of movement data – hopefully giving us an inside look into the secret lives of these beautiful animals and ensuring that we do everything within our power to conserve and protect a species in desperate need of our help.