Tag – You’re It: scientists unravel the link between whale sharks and tunas

The whale shark is possibly the most iconic shark on the planet. There are many known aggregation sites across the tropical oceans, including the western Atlantic Ocean, but their presence in the temperate oceanic islands of the Azores in the NE Atlantic, was quite rare until 2008. The local pole-and-line tuna fisherman knew of their existence and how sometimes they were found to harbour vast tuna schools. However, between 2008 and 2013, the Azores fisheries observers reported more than a thousand whale shark sightings. Whale shark abundance in the Azores was coincident with abnormally warm summers and fishermen were getting higher yields when fishing the more diverse schools with smaller tunas travelling with whale sharks compared to free swimming schools.

Fishing skip jack tunas associated with a whale shark off Santa Maria Island. Photo © Nuno Sá

After five consecutive years of summer visits, the whale sharks simply were no longer visiting, much to the disappointment of tourists, fishermen and scientists. As a young post-doc, with great plans to investigate this unique aggregation of mature whale sharks, where both sexes were found together. It wasn’t all bad, the many hours and days spent with the local fishermen searching for whale sharks and observing these massive sharks surrounded by tuna and bait balls, around Santa Maria Island, give me a unique perspective and insight into this mysterious whale shark-tuna association and how the local fishers interact with them.

In 2019, the whale sharks returned, and we were ready. During the whale shark absence, we focused on developing state-of-the-art non-invasive tools to investigate the behaviour of large sharks and mobula rays. So, when the whale sharks finally returned, we were ready and well-equipped to investigate the unique whale shark-tuna aggregations in the Azores. During this period, we were able to tag a few dozen sharks, photo ID, size and sex part of the population. The more we learned about the behaviour of these oceanic whale sharks, the more questions we had about the association with the tunas. While the forward-facing camera provided us with a unique window for in situ observation, its autonomy is limited to 10-h maximum, and we can only observe what happens in the first few meters in front of the whale sharks. We needed to complement that information with longer-term longer-range tools to gain more insight into the significance of the whale shark-tuna association.

Salto e Vara fishing skip jack tunas with the traditional live bait rod, one by one style.

Fortunately, SOSF believed in our crazy ideas and is on board with us in one of our most ambitious projects so far. This unique approach is a high risk, high reward. If successful, it will help clarify one of the most intriguing and meaningful natural history stories from the open ocean. Tagging whale sharks and tunas, is something many, like us, have done successfully in the past, however doing it simultaneously is a totally different story. Everything needs to align perfectly. We “just” need one team ready to tag tunas on a small fishing boat searching for a whale shark with a tuna escort, which needs to be in the right mood to take the live bait offered by the fishers. The fishing starts, and the whale sharks stick around, while the whale shark tagging team comes in, slowly gets in the water, to tag the whale shark with the specifically tailored tag to detect the tagged and released tunas. Simple, yes? Ahh, we also need a window of good weather to tag and then recover the whale shark tag, after a few days, to download the data. Hopefully the shark is hanging in the area. Don’t forget this is all happening in the middle of the NE Atlantic Ocean, not in the tropics or inside a sheltered bay.

After much preparation, we are finally ready to fly from Faial Island to Santa Maria, some 190 nautical miles southeast. Captain Silvino has been reporting a decent number of encounters with whale sharks and tunas, and the weather forecast looks promising. We arrive to transform the fishing boat into a tuna fishing and tagging machine. We need to install the directional acoustic hydrophone on the fishing boat so we can hopefully monitor the released tunas and potentially track the tagged whale shark. The BioFAD tag on the shark will carry an acoustic, satellite and radio transmitters, to aid in finding the tag, along with an acoustic receiver, accelerometer, depth, and water temperature sensors. Salto e Vara, the fishing/science ship is ready, the only thing missing now is fresh live bait. While Captain Silvino takes Salto e Vara to replenish the live bait wells, we take the RIB Manta to check the action and get a feeling for the next day. Just a couple of miles out, we see increasing bird action, then bait balls and lots of tuna, and finally our first whale shark of the season is there, under a massive bait ball and surrounded by tunas.

Picture of WS under massive bait ball of snipe fish, surrounded by big-eye tuna. Photo © Jorge Fontes

We jump in and tag the shark with a SPOT satellite tag that may perhaps help us locate the elusive sharks over the next few days. Another shark, another tag. Two more encounters but we only brought two tags for the first afternoon (to not get greedy right away). We still have time to visit the Ambrosio seamount, where Chilean devil rays (Mobula tarapacana) aggregate in the summer, and give another go at deploying the new prototype tag, designed to measure activity and the internal temperature of mobula rays. The day is going well; we got the first successful Mobula internal temperature tag attachment. Although it was released prematurely, these are the first internal temperature data in history. Not a bad start, things are looking good.

Group picture with science and fishing crew with Salto e Vara on the background. Photo © Pepe Brix Documentary Photography

We meet Captain Silvino and the crew a couple of hours before sunrise to go over the plan, once more. Captain Silvino calls out, “Release the lines” and Salto e Vara is off, followed by the RIB Manta, and the rest of the gang. Hours into the day, many miles sailed around Santa Maria Island, under a scorching sun, and the excitement and confidence from the day before started to wear down. The news from other captains are not great, not much whale shark action today. We wait for satellite locations from the tagged sharks, refresh the app frequently, and nothing. Many bait balls with big eye tuna and some blue fin, but the crew is not interested, the fisheries for the big tuna are closed. After twelve hours of relentless searching, tired eyes and just a few skipjacks below deck, Captain Silvino steers Salto e Vara to Vila do Porto port. Same time tomorrow, we agree, sleep fast and try to get some rest for tomorrow. When the sun rises behind the island, we have just arrived at the fishing grounds. More of the same, big tunas, birds, and bait balls. It’s beautiful and one of the most amazing scenes you can witness, but the whale sharks are still missing. It´s past 2 PM, and we decided to cover more ocean, by sending the Manta and Salto e Vara in different directions. After a couple of hours, Manta finds a massive female shark, close to where we had tagged the two sharks. It’s escorted by tunas, small big-eye, perfect for tagging. We call Salto e Vara, but it’s too far and too slow, so another satellite tag is deployed. We take some shots for photo ID and measure the colossus using a camera system with paired lasers. Still no locations from the other two sharks. This could mean that tags have failed, or that the sharks are simply not spending enough time at the surface to expose their dorsal fin/tag. If the sharks are deeper, they are impossible to find. Nothing worth reporting until it’s finally time to sail back to port. The debrief brings troubling news, and the pressure builds as the forecast shows a few tropical storms making their way across the North Atlantic to the Azores.

The next day, we finally have a location from one of the tagged sharks, maybe they are shallower. We call all the captains and dive operations to make sure they give us a shout in case they find a shark. Soon enough, we get the first call from a captain, a couple of sharks were sighted up north, but almost immediately we get a satellite location in the south. Predicament: what to do? We decided to concentrate the search in the south, where we were seeing plenty of birds, tunas and bait balls. Beginning of the afternoon, Salto e Vara calls Manta, “We have a shark with tuna, come over, fast”.

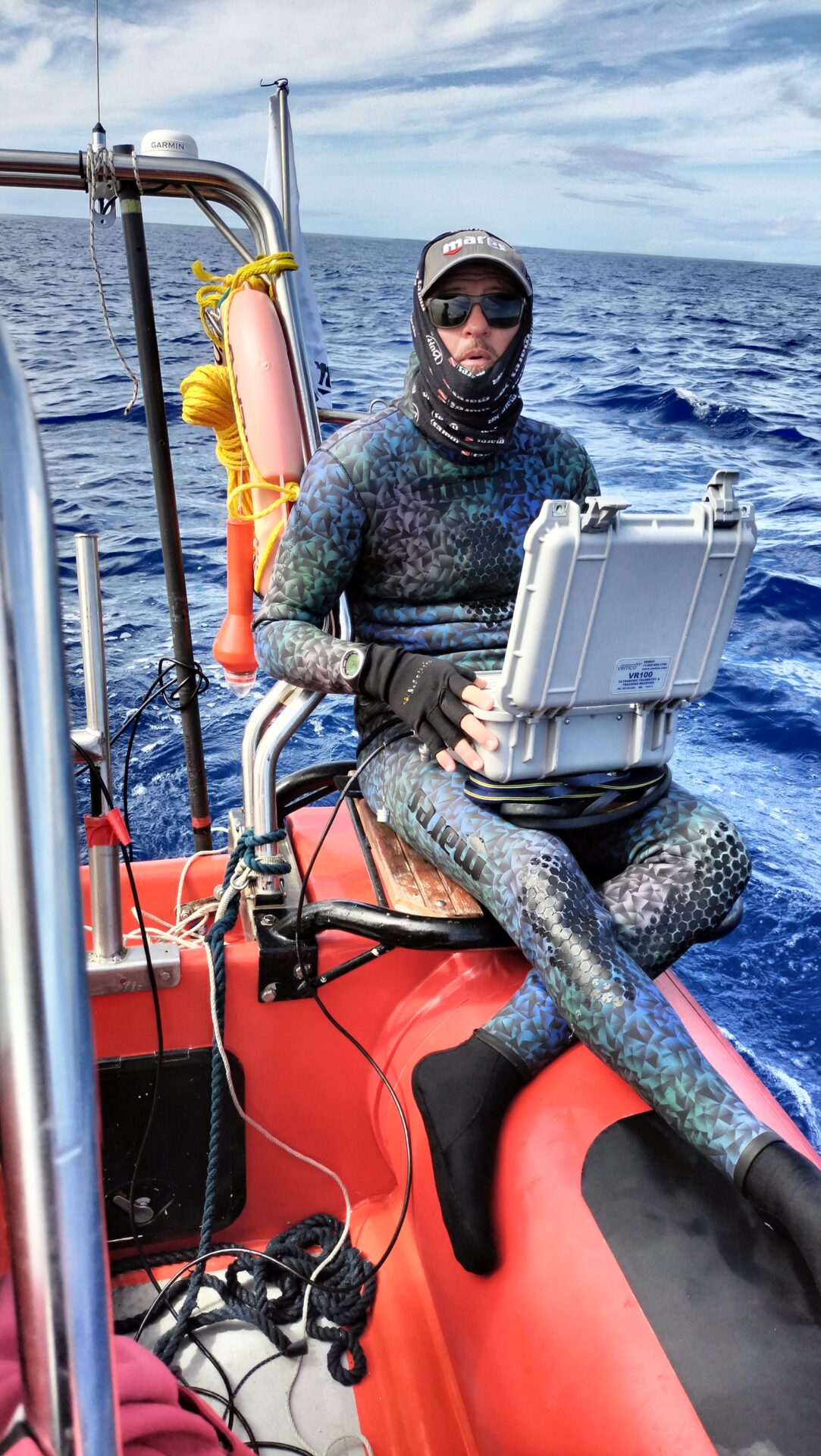

Bruno Macena is doing the last fine tune of the BioFAD multisensor tag before it is deployed. In the background, Salto e Vara is preparing to fish and tag tunas. Photo © Jorge Fontes

The tunas are a bit larger than ideal, but we decide to go for it. The first big eye is tagged and returned to the ocean. We get in the water very slowly, take the time, wait for the shark to come check us out, and gently deploy the tag.

Pedro Afonso implanting an acoustic tag on a bigeye tuna with the help of the fishing crew. Photo © Pepe Brix Documentary Photography

All appears to be going well, the second big eye was tagged and released. “Captain, can you see the shark?” we ask from the RIB. Captain Silvino reports disturbing news from the flybridge, the shark decided to swim off, although the tunas remain. Disappointment and frustration, but it’s not game over just yet. We continue to search the area for the tagged whale shark and may still get another shot. More sighting reports come from captains and dive boats, but none have a red torpedo tag attached. We can still try to find it with the acoustic hydrophone, so we start a search pattern to cover the 5 NM area around the first fishing event. We spot a few more sharks, with no tags, we measure and photo ID and deploy the last satellite transmitter. Unfortunately, the day ends with no sign of the tagged shark.

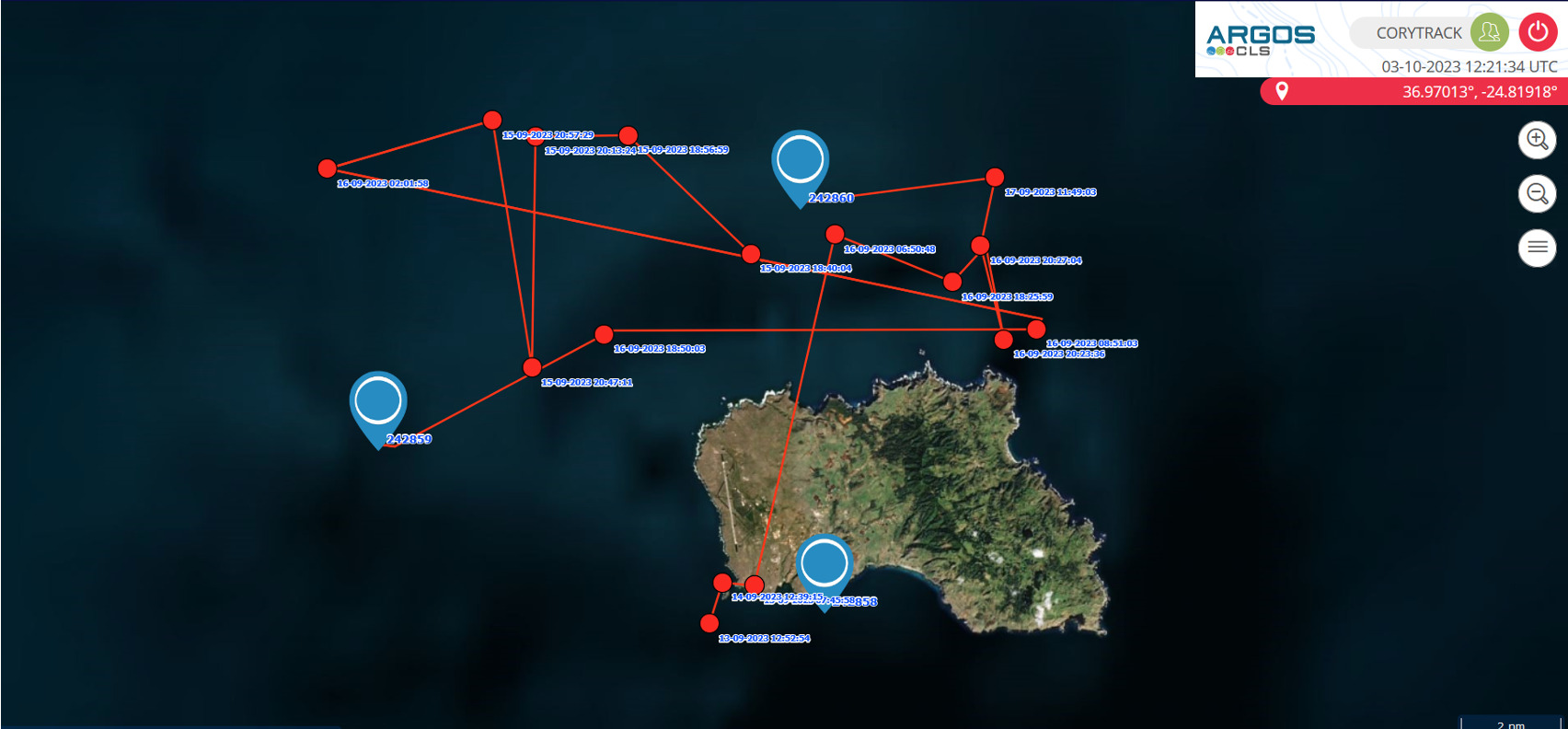

Image of the tagged sharks locations from the CLS Argos web portal.

Bruno Macena monitoring the presence of acoustically tagged whale shark and tunas. Photo © Jorge Fontes

Three hours until sunset, we continue the search, its still possible to score big before the final whistle. Another massive shark with lots of large tunas, but no tag. Salto e Vara continues to search as its steams back to the harbour and Manta follows soon after.

As the weather kicks in we are grounded for at least one week. We have one tagged shark and two big-eye tunas transmitting, this is an awesome result. Although our goal was to tag 30 tunas, we have now shown, for the first time, that this crazy idea works, with a little bit more luck and Poseidon’s good graces we will get the rest of the tags out soon. Yet, we still need to recover the BioFAD tag, scheduled to release from the shark in three days, during the storm. As scheduled, the tag pops off and transmits its location, but can’t go out until the weather improves, and the tag drifts offshore for the next three days. Finally, we get a chance, and 80 NM later, we have the tag back. We download the data and success! We have detections from the day following the tagging. This is proof-of-concept and it’s epic, showing that the crazy idea may in fact not be that senseless after all. These very preliminary results align with our expectations that large tunas possibly don’t overlap with whale sharks as frequently as the smaller tunas.

Despite the abnormally rough weather in an El Niño year, these results boost our confidence to continue this project. This landmark would not have been achieved without the help of Captain Silvino and crew, all the fishers, dive operators, the community from Santa Maria Island and Save Our Seas Foundation support.

Stay tuned for more developments.