Unveiling the value of kelp forests as sharks’ and rays’ nesting sites in Chile

“I can only compare these great aquatic forests of the southern hemisphere with the terrestrial ones in the intertropical regions. Yet if in any country a forest was destroyed, I do not believe nearly so many species of animals would perish as would here, from the destruction of the kelp” – Charles Darwin, referring to the kelp forest of Tierra del Fuego, 1909, the voyage of the Beagle.

My name is Ítalo Fernández, and for over a decade, I have been diving into the cold waters of the Humboldt Current system. In these temperate marine environments, you can find dense kelp forests that enhance the life of rocky reefs. This underwater realm is particularly special to me because it teems with more life than even the terrestrial forests of my region. Here, it’s not uncommon to encounter large schools of fish or diverse arrays of crabs and snails.

Eggs on a piece of kelp. Photo © Alejandro Pérez Matus

Building on this rich marine biodiversity, the kelp species Lessonia trabeculata, also known by its common name “Huiro” (from the Quechua word “wiru”), serves as both a refuge and a vital food source for numerous fish and invertebrates. Less known, however, is its role as a nesting ground for various species, including different types of sharks and rays that thrive in these kelp forests. The intricate evolutionary relationship between these elasmobranchs and the macroalgae remains unexplored mainly, sparking my curiosity and research focus.

A huge “egg clutch” of the Chilean chatshark (Schroederichthys chilensis) entangled in the stypes of a “Huiro Palo” (Lessonia trabeculate) within the kelp forest of Punta de Tralca, Chile. Photo © Nicolás Acuña

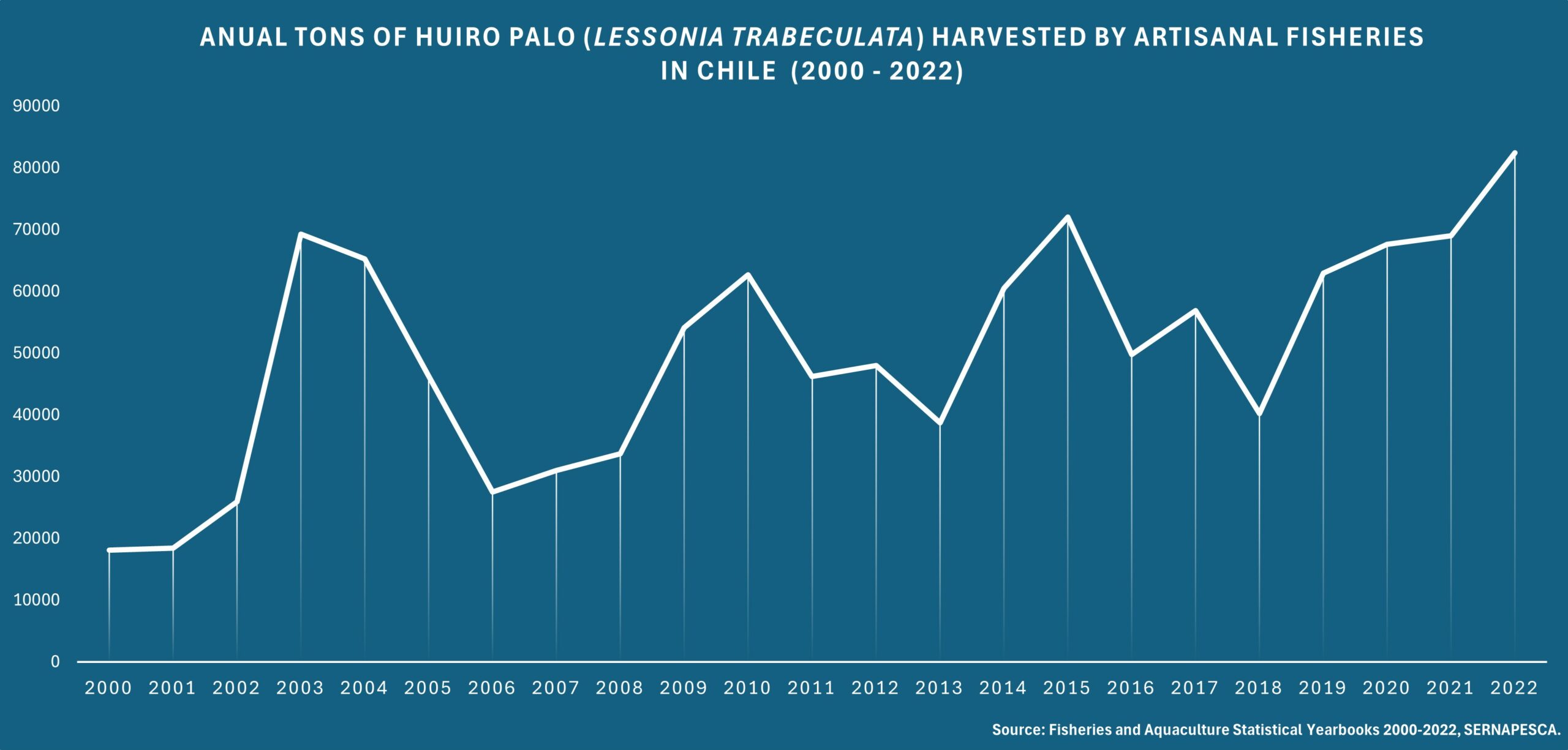

As we delve deeper into the ecological challenges, Chile’s position as the world’s leading harvester of natural kelp beds comes with increasing ecological concerns. Harvest volumes have been growing steadily for the last 20 years, benefiting the economy of coastal communities but potentially devastating the biodiversity of over 200 associated species, as Darwin stated more than one hundred years ago. However, this often-overlooked destruction continues unchecked with no significant regulation to curb kelp extraction. We must find ways to assign a conservation value to these vital organisms to support the marine life and the coastal towns across Chile.

A truck towing kelp harvested the same day in Chañaral de Aceituno, Chile. Photo © Gabriela Winckler

In collaboration with my research team of the Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, we strive to emphasise kelp’s conservation value by highlighting its role as “nesting trees” for charismatic coastal species. My project focuses primarily on the small species of sharks and rays that rely on these marine forests to nurture their young. We have planned several expeditions along Chile’s extensive coastline, stretching thousands of kilometres. Despite this quest’s considerable effort, this daunting task is fuelled by our passion and commitment to preserving our marine ecosystems. Our expeditions will take us from the seas off the world’s driest Atacama desert to the frigid southern waters bordered by lush Valdivian rainforests. We aim to understand how elasmobranch species utilise these underwater forests as breeding grounds by studying the biological and abiotic factors affecting their choice along Huiro distribution.

Annual tons of huiro palo harvested along Chilean coast between 2000 to 2022. Image © Antonia Valentino.

Our journey so far has led us to identify more than six potential research sites, expecting to discover many more. While we wait for optimal diving conditions, we continue to track the movement and residency patterns of the catshark within marine forests. Have I mentioned that we have also deployed a series of acoustic receivers? These devices are crucial for monitoring the movements of these small sharks both within and outside the Las Cruces Marine Reserve, a known nesting area. This method provides fascinating insights into how and when these sharks utilise the forest throughout the year, during the reproductive season and beyond.

A Chilean catshark resting on the bottom. Photo © Vladimir Garmendia