Unpacking the epic battle between sharks and orcas in South Africa

A significant change has taken place in the pecking order of South Africa’s marine predators over the last few years, with great white sharks, the previous undisputed ‘kings of the sea’, being unceremoniously (and pretty viciously) displaced from the top by a pair of orca ‘affectionately’ nicknamed Port and Starboard.

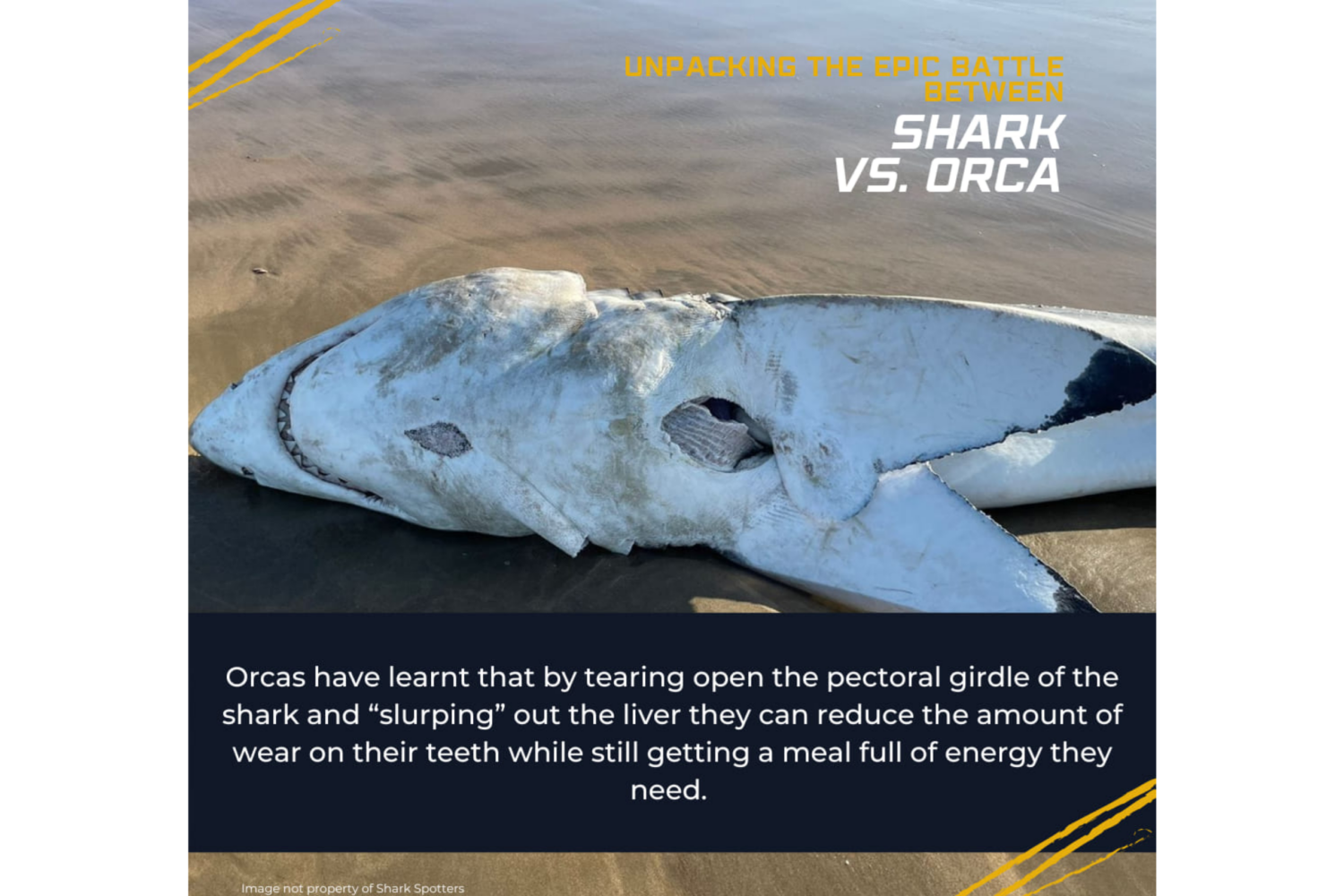

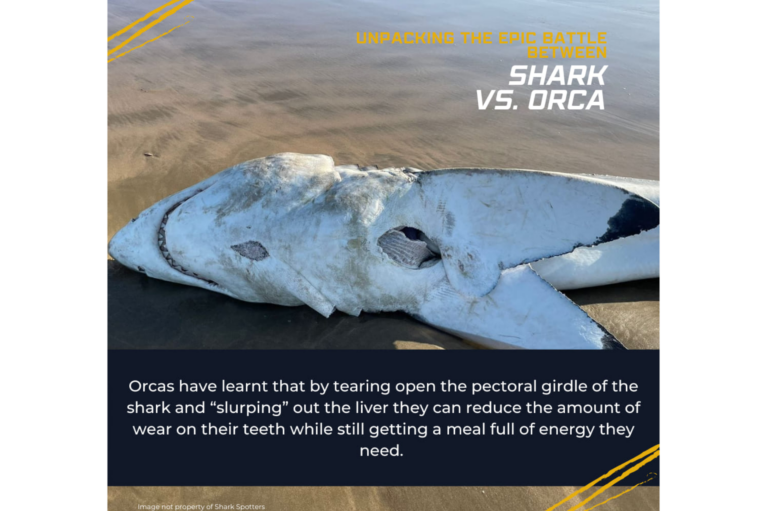

Just recently, in August 2022, Drone Fanatics reported a great white shark carcass washed ashore in Mossel Bay with all too familiar signs of orca predation – a tear in its pectoral girdle and missing vital organs. This happened just a day after a pod of orcas was seen cruising the area.

While the story is still unfolding, with new evidence and information coming to the surface all the time, we thought it would be helpful to go back to the beginning and unpack this epic yet concerning battle from when it started, over seven years ago!

But first, let us answer an important question:

A dead white shark washed ashore. Photo © Drone Fanatics SA

Do orca’s normally eat sharks?

There are different ecotypes of orca in the higher latitudes of both hemispheres that specialise in eating very specific prey types. For example, the resident orcas in the North Pacific feed almost exclusively on salmon, or transient orcas from Argentina feed on sea lions and other pinnipeds. Off the coast of South Africa, orcas tend to be more generalised in their diets; however, a more specialised group has been identified and is believed to feed predominantly on sharks.

What is the evidence that orca’s are predating on sharks?

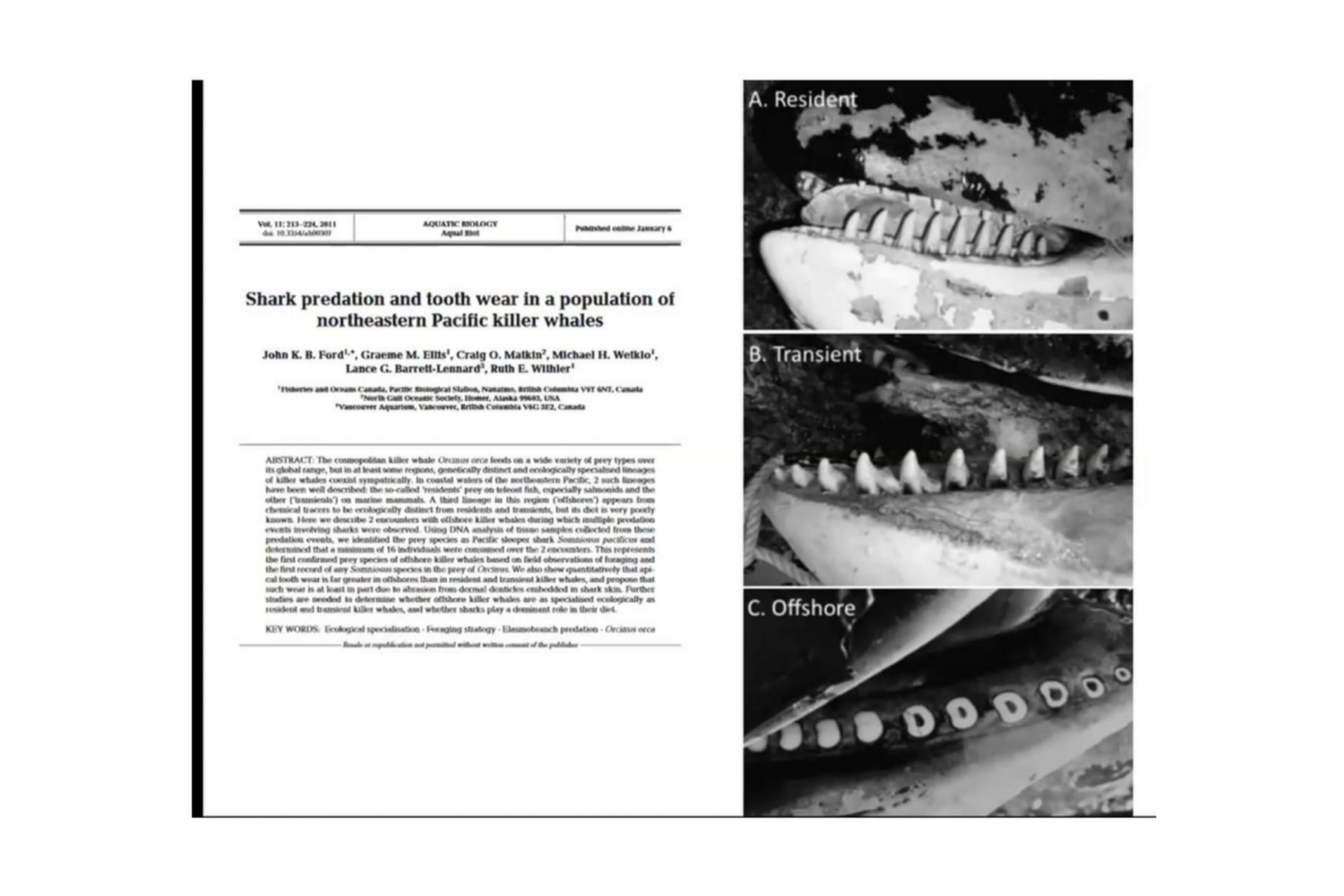

While rare, when orca carcasses wash ashore, they can provide invaluable information for scientists. Ford et al. (2011) compared the teeth of resident, transient and offshore orcas in the North Pacific. They found that offshore orcas, observed to be predating on sharks, had significantly flattened and worn down teeth compared to resident and transient orcas who fed on fish and marine mammals.

Sharkskin comprises dermal denticles, small teeth-like structures that reduce drag and make the shark more streamlined. The dermal denticles are highly abrasive and act like sandpaper on the teeth of orcas (or other predators), wearing down the enamel and flattening them into pegs. According to Best (2014), since 1969, three orca carcasses with worn-down teeth and sharks in their stomach have washed up in South Africa, confirming that these offshore shark-eating orcas are also present in our ocean.

Why do the orcas only eat the shark’s livers and not the whole shark?

Due to the abrasive nature of shark teeth, repeatedly tearing large chunks of shark flesh would wear down the orca’s teeth exceptionally quickly. Given that a shark’s liver can weigh up to one-third of its body weight and is highly energy-rich and dense in calories; orcas have learnt that by tearing open the pectoral girdle of the shark and “slurping” out the liver, they can reduce the amount of wear on their teeth while still getting a meal full of energy.

The first signs of orcas eating large coastal sharks in South Africa

While the first great white shark carcasses started coming ashore in Gansbaai in 2017, in False Bay there were already signs of orca-shark interactions two years before.

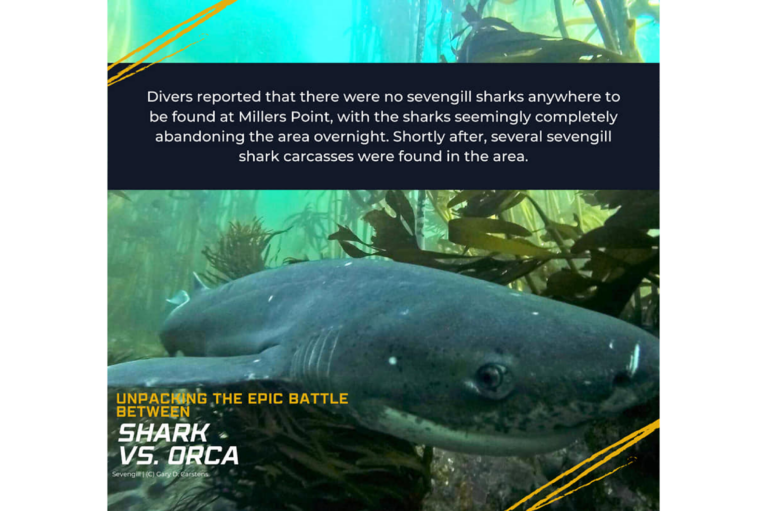

Prior to 2015, Millers Point, on the Western side of False Bay, was a well-known aggregation site for broadnose sevengill sharks (Notorynchus cepedianus), with recreational scuba divers regularly seeing up to 70 sharks on a single hour-long dive. Sevengill sharks feed on many of the same prey as white sharks, including seals, and it was thought that they aggregated at Millers Point during the day to avoid competition and potential predation from white sharks, and then ventured out to feed at night when the risk of running into a white shark was lower.

Shark Spotters had acoustically tagged over 70 sevengill sharks at that time, with research led by Alison Kock, Tamlyn Engelbrecht and Leigh de Necker, to investigate their movement ecology and determine their trophic role in False Bay. This research was carried out with the Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa at the University of Cape Town and was funded by the National Research Foundation , Save Our Seas Foundation and the Two Oceans Aquarium.

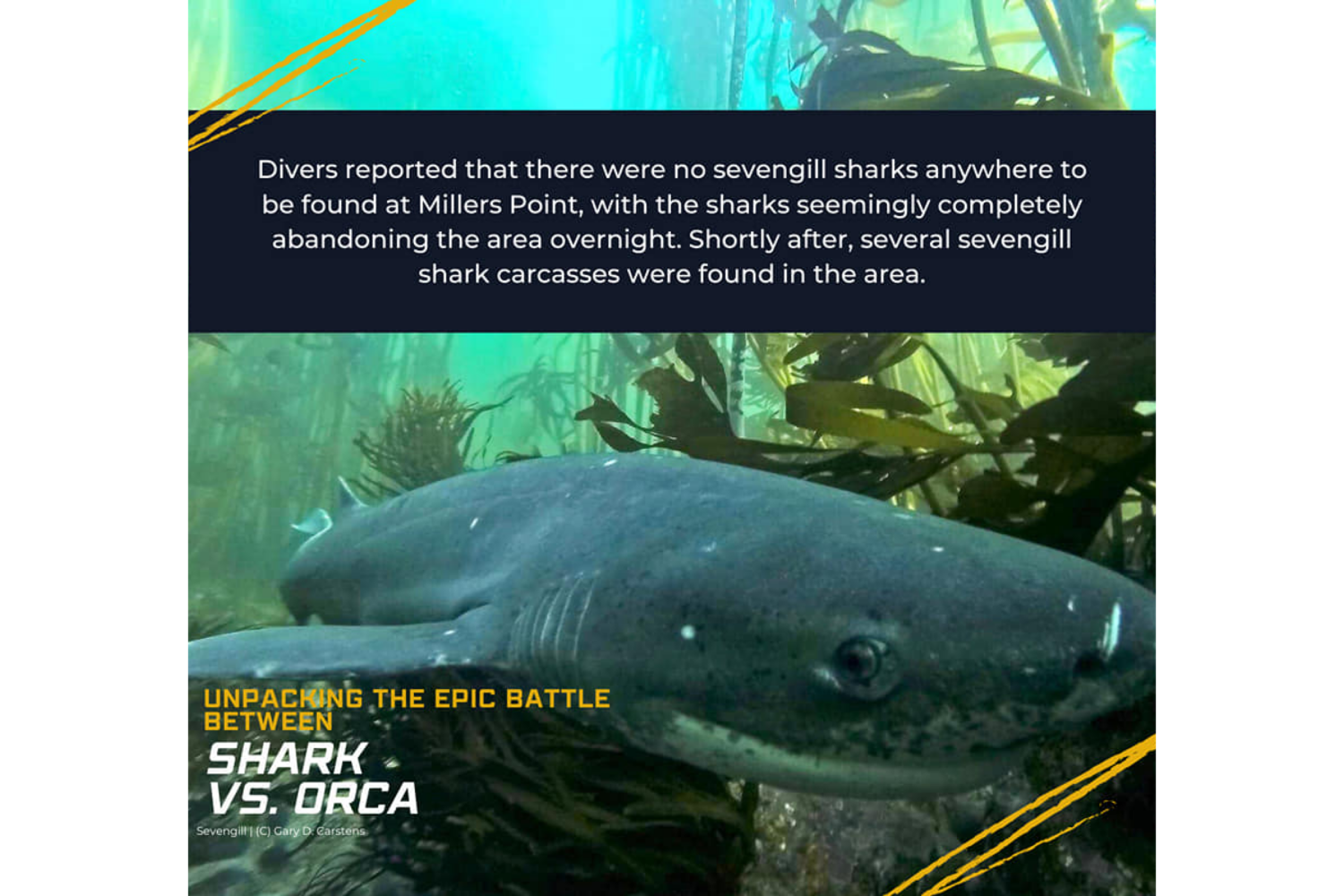

Just as predictable patterns of habitat use were starting to emerge, everything changed, and within the space of 24 hours, the sevengills were gone! On 9 November 2015, divers reported that there were no sevengill sharks anywhere to be found at Millers Point, with the sharks seemingly completely abandoning the area overnight. Shortly after, several sevengill shark carcasses were found in the area. Unfortunately the carcasses were not retrieved and so only photographic evidence of them was obtained.

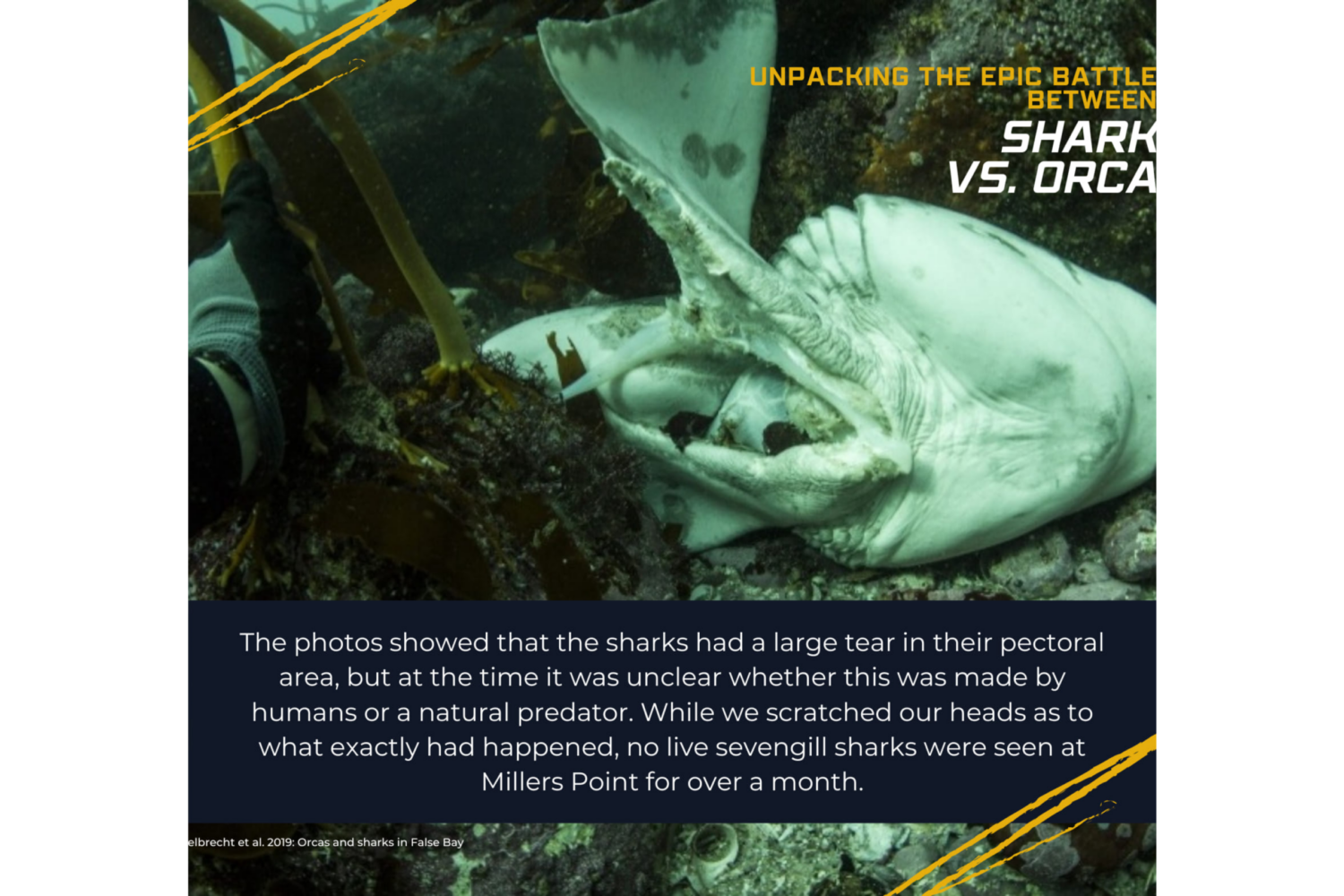

The photos showed that the sharks had a large tear in their pectoral area, but at the time it was unclear whether this was made by humans or a natural predator. While we scratched our heads as to what exactly had happened, no live sevengill sharks were seen at Millers Point for over a month.

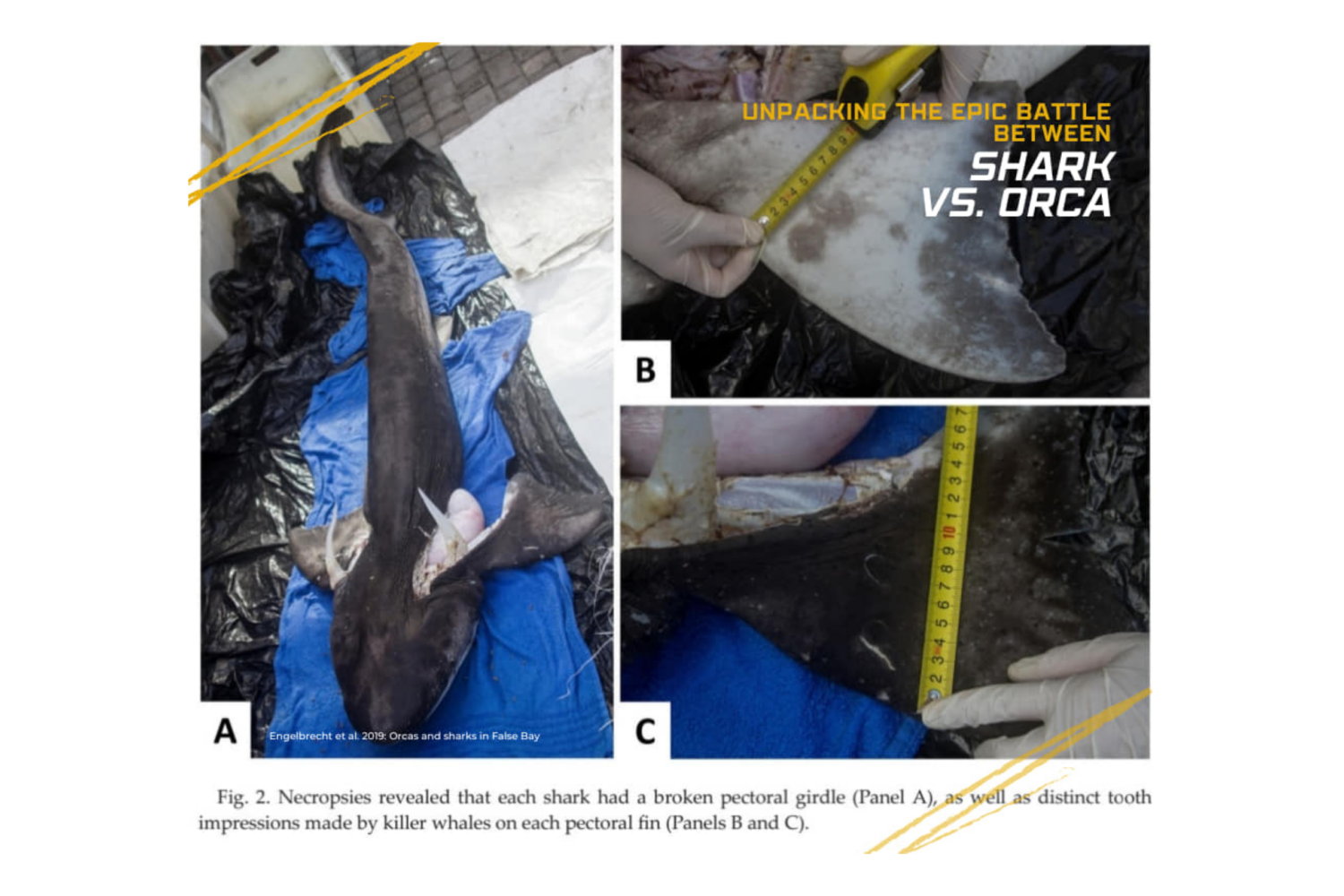

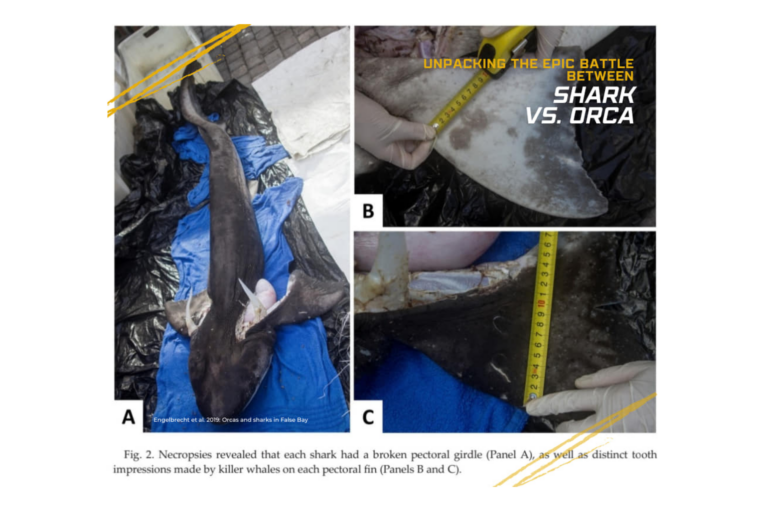

By the beginning of 2016 the sharks had started returning to their aggregation site and it appeared that everything was going back to normal. That is until April 2016…when it happened again! Carcasses of sevengills suddenly appeared in the area. This time five carcasses were retrieved and scientists were able to conduct necropsies to better understand exactly what had happened.

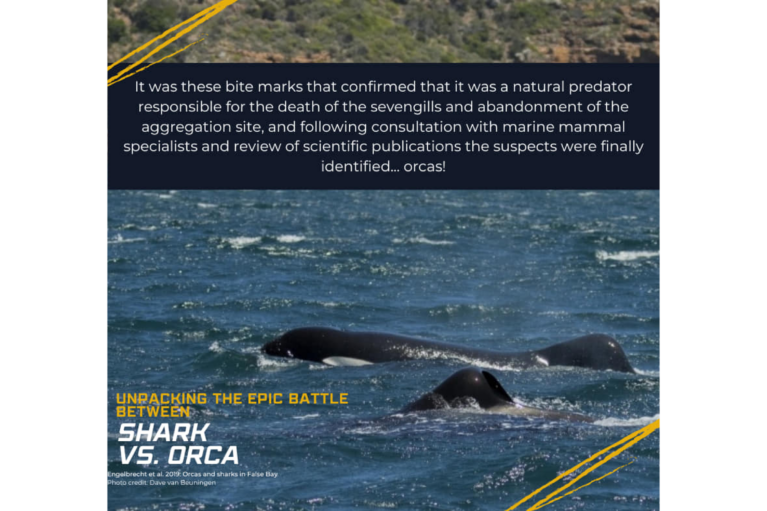

All of the carcasses were intact except for a large tear across the pectoral girdle, similar to what had been seen in the photographs from the carcasses seen in November 2015. Further examination found that in each carcass the liver of the shark was missing, with all other organs still intact. The pectoral fins of the sharks showed evidence of bite marks and bruising, prompting the scientists to re-examine the images from the previous carcasses, which showed similar tooth indentations. It was these bite marks that confirmed that it was a natural predator responsible for the death of the sevengills and abandonment of the aggregation site, and following consultation with marine mammal specialists and review of scientific publications the suspects were finally identified: ORCAS!

While it was well known that orcas targeted sharks far offshore, this was the first time evidence had been found of orcas eating large coastal sharks close to shore!

The notorious duo: Port and Starboard

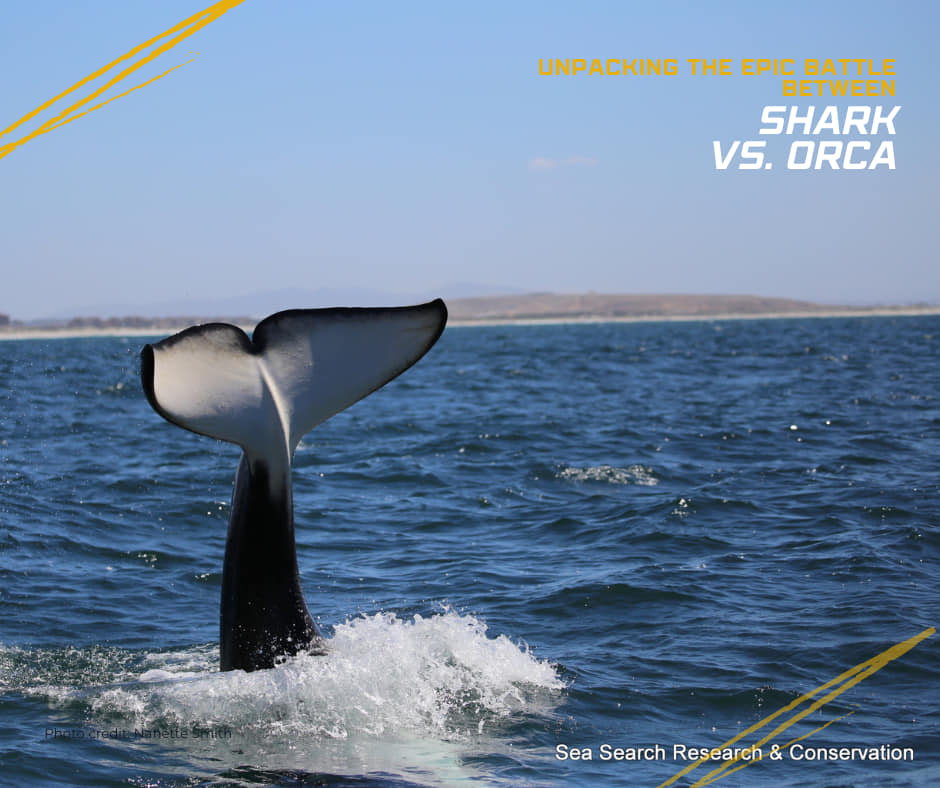

According to Dave Hurwitz from the Simon’s Town Boat Company who has a wealth of knowledge about all things cetacean (whale and dolphin) and has been running licensed whale watching tours for over 20 years in False Bay, historically, he had witnessed orcas feeding on dolphins in the bay. However, in 2015 two new individuals entered the bay who were easily recognisable by their collapsed dorsal fins. Each orca’s fins bent in a different direction, one to the left and one to the right, and so Dave affectionately nicknamed them “Port ” and “Starboard” – shipping terms for the left and right side of a boat.

At first these two orcas seemed no different to the others that had been seen in the bay, however this soon changed when the shark carcasses started turning up. In fact, Port and Starboard were seen in the Millers Point area in the week before and after the two events where sevengill carcasses were found and the sharks abandoned their aggregation site. This seemed like too much of a coincidence once the sevengill necropsies confirmed orca’s were responsible for the shark deaths, and when white shark carcasses started washing ashore in Gansbaai in 2017 around the same time as Port and Starboard were seen in the area scientists were able to confidently identify them as the perpetrators!

Port and Starboard hit Gansbaai

According to Alison Towner, Marine Biologist for Dyer Island Conservation Trust and PhD candidate at Rhodes University, in early February 2017, tourists and guides on the Marine Dynamics shark diving boat in Gansbaai were excited to witness two killer whales with bent dorsal fins hanging around the cage diving area. A rare spectacle at the time, the people onboard considered themselves lucky to have seen these special animals up close. That was, until the next day, when a 2.6m female white shark carcass washed out at Pearly Beach! Immediately the connection was made between the previous day’s visitors and the dead shark… Port and Starboard had found new hunting grounds 150km up the coast from False Bay.

However, this shark was intact, there was no tear at the pectoral girdle and the shark’s liver was still present, so scientists at the time were unable to conclusively confirm that the shark had been the victim of orca predation, although it was highly likely.

Sadly, over the next few months confirmation came in the form of a further four white shark carcasses washing ashore in Gansbaai – three in May 2017 and one in June 2017. The sharks ranged in size from 3.6m to 4.9m, and included both males and females. A consortium of shark scientists including Alison Towner (Dyer Island Conservation Trust), Alison Kock (SANParks/Shark Spotters), Meaghan McChord (South African Shark Conservancy), Sarika Singh (DFFE) and Malcolm Smale (Bayworld Museum) conducted necropsies on all sharks to determine the cause of death.

Each shark had their pectoral girdle torn open and were missing their entire liver. One shark was also missing its heart and testes. Two of the sharks had clear killer whale rake marks (scratches from killer whale teeth) on their bodies. This evidence led the scientists to confirm that orcas had been responsible for the shark deaths. Coupled with sightings of Port and Starboard in the Gansbaai area around the time of the carcasses coming ashore, there was no room for doubt that our floppy-finned apex predators had developed a taste for white sharks!

This blog is the first in a series exploring the fascinating developments between sharks and orcas on the South African coast. Check in next time to learn more about the impacts of orcas on white shark distribution and abundance along our coastline, and what this means for the future of an already threatened apex predator.

- Extra Resources

- References

Orca-sevengill interactions

Video | Running scared: when predators become prey – Seminar Series – Scientific Services – SANParks

Article | Running scared: when predators become prey | Save Our Seas Magazine

Orca – cetacean interactions

IMDb| Killer Whales: The Mega Hunt (2016)

Video | Pod of Killer Whales Hunt a Dolphin Stampede

All about the floppy fins

Article | The incidence of bent dorsal fins in free-ranging cetaceans

Facebook Post | Why the floppy fins?

Facebook Post | Conducting necropsies on white sharks Part 1 and Part 2

Alves et al. 2017. The incidence of bent dorsal fins in free-ranging cetaceans. Journal of Anatomy, 232, 2, 2018

Best PB, Meÿer MA, Thornton M, Kotze PGH, Seakamela SM, Hofmeyr GJG et al. 2014. Confirmation of the occurrence of a second killer whale morphotype in South African waters. African Journal of Marine Science 36: 215–224

Engelbrecht, T. M., A. A. Kock, and M. J. O’Riain. 2018. Running scared: when predators become prey. Ecosphere 10(1):e02531. 10.1002/ecs2.2531

Ford JKB, Ellis GM, Matkin CO, Wetklo MH, Barrett-Lennard LG, Withler RE. 2011. Shark predation and tooth wear in a population of northeastern Pacific killer whales. Aquatic Biology 11: 213–224