The world’s largest treadmill – for fish

Words by: Nick Payne

Measuring how much energy animals use for their daily activities can be really useful. It can give us an idea of how much food they need to eat and how long they may be able to spend running or swimming at high speeds. It can even help us understand why animals can live in one habitat but not in others. We usually talk about an animal’s rate of energy expenditure in terms of metabolic rate, and scientists have come up with lots of cool ways of measuring metabolic rate during different levels of animal activity, such as resting, running, hopping or swimming.

For land animals, pimped-up versions of treadmills (like those in a gym) are standard.

The subject walks or runs at a range of different speeds and the rate at which it consumes oxygen (or produces carbon dioxide) is measured to determine its metabolic rate. We use a similar method for animals that live in water, albeit with a few important differences.

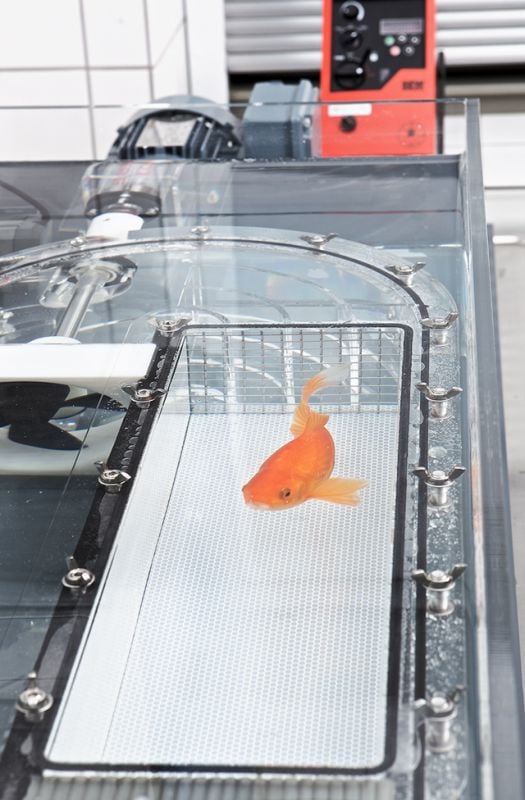

A ‘swim-tunnel respirometer’ is basically a treadmill for fish. At the most basic level, swim-tunnel respirometers are sealed, near-circular chambers in which water circulates at different speeds in order to encourage a fish (or any other water-breathing animal) to exercise at different levels.

Much in the same way as for a treadmill, scientists then measure how much oxygen the fish consumes from the water inside the respirometer to estimate its metabolic rate.

Swim-tunnel respirometers have a fairly long history (at least 50 years or so) and are quite common pieces of equipment these days for fish physiologists all over the world. As you can imagine, building a device in which you have fast-flowing water, at controlled speeds, in a sealed container, that houses live fish, comes with a few logistical (and financial) challenges. As a result, swim-tunnel respirometers have been restricted in size to accommodate fish no larger than about 10 kilograms. This means that we have relied on a fair bit of guesswork when it comes to assessing the metabolic rates of larger fish and sharks.

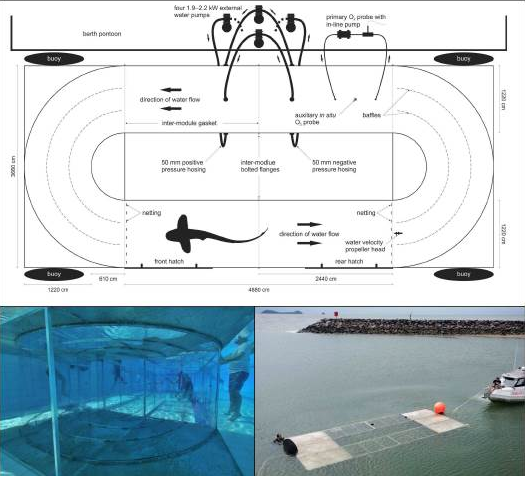

That is, until now. Recently we (a team from the National Institute of Polar Research in Japan, the universities of Adelaide and Tasmania and James Cook University) built a huge swim-tunnel respirometer that holds about 26 tonnes of water and can be used for fish and sharks of at least 100-kilogram body mass.

We tested this ‘mega-flume’ with a 2.1-metre zebra shark Stegostoma fasciatum swimming at 40 cm per second – and it worked. We compared our data to measurements from other sharks swimming around in tanks and our results matched quite well.

We are now planning to use the mega-flume with lots of other big sharks and fish. There are hardly any data on the metabolic rates of these animals, so much of the information we can get from this new device will be new and exciting.