The tip of the movement iceberg

Man has always been inspired by the sea, driven to learn more about it and the creatures living beneath its surface, with particular interests in how and where they move. But historically, this has always been difficult to do, because following an animal 24/7 is next to impossible, especially in the marine environment. Enter the age of technology, and the onset of acoustic telemetry! The first study using acoustic tags took place in the 1960s, almost 70 years ago, but technology has progressed exceptionally quickly since then, with smaller tags being produced capable of monitoring smaller animals than ever before, as well as long-life tags making it possible to track an animal for up to 10 years!

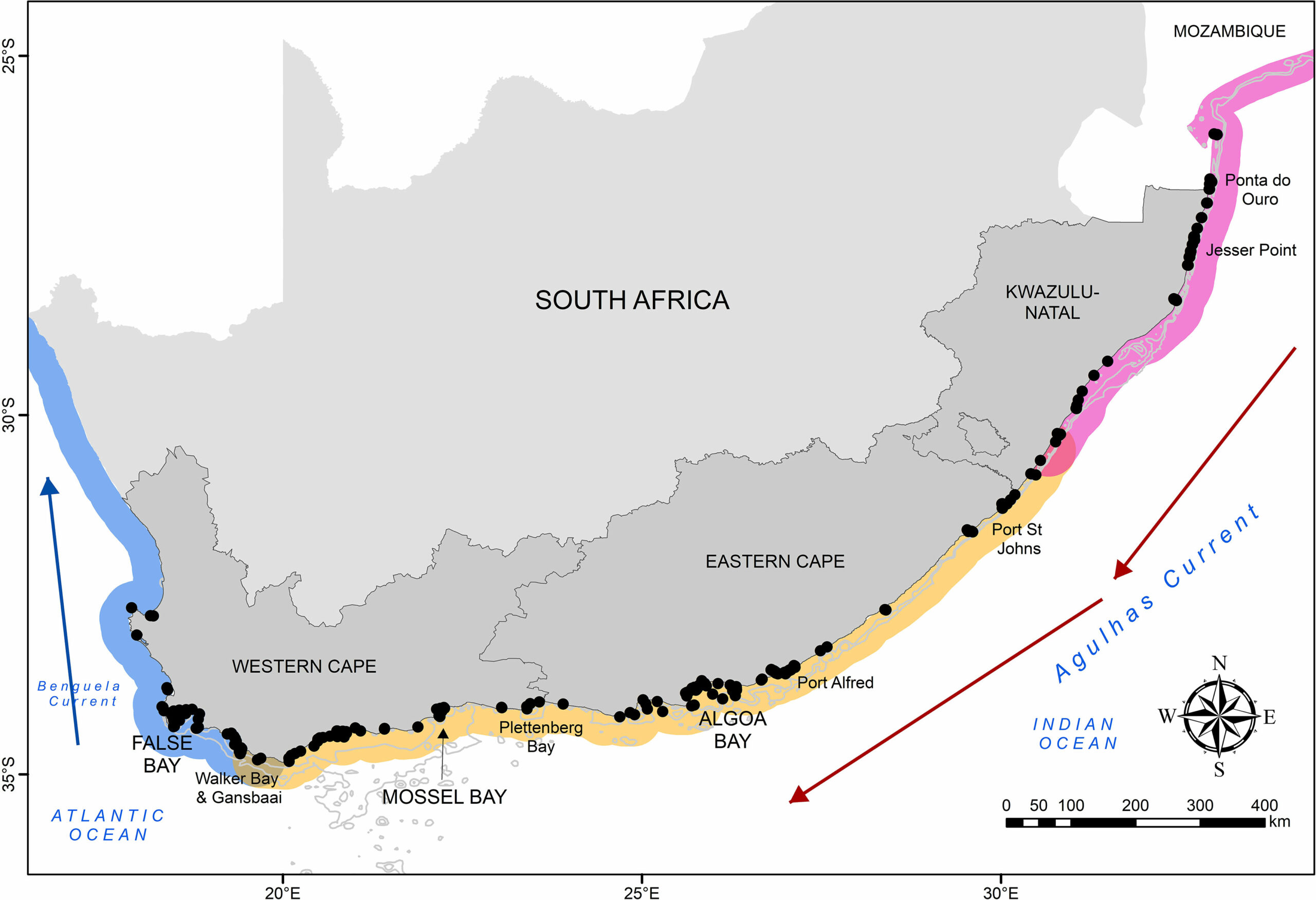

Despite these tremendous technological advances and management authorities beginning to realise the importance of incorporating movement behaviour into management regulations and plans, movement information of many important fishery species is lacking, and many species remain understudied. Over the past 12 years, the Acoustic Tracking Array Platform (ATAP), a large-scale acoustic receiver array at the southern tip of Africa (covering ~2200 km/1370 miles of the South African and southern Mozambique coastline) has been collecting movement information of 51 species including 24 shark and nine ray species. These range from large predatory sharks such as white sharks, bull sharks and tiger sharks, to important fishery species such as bronze whaler sharks, soupfin sharks and smoothhound sharks, endemic species including flapnose houndsharks, pyjama and leopard catsharks and blue stingrays, and Critically Endangered stingrays such as whitespotted wedgefish, common eagle rays and duckbill rays.

The locations of receivers (black dots) forming the greater Acoustic Tracking Array Platform currently deployed along the South African coastline. Image from https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.886554

Despite more than 1070 individuals being tagged and the plethora of data associated with these tagged animals (together amassing over 5.5 million detections), we really are only touching the tip of the iceberg in terms of learning more about the movements of these species. In a recent conference presentation at the 7th Southern African Shark and Ray Symposium held in Durban between 25 and 27 October 2023, Dr Taryn Murray, ATAP Instrument Scientist, highlighted aspects of the movement ecology of several species that have been revealed through the data collected by the ATAP. For example, important movement corridors for blue stingrays along South Africa’s southern coast have been identified, estuaries have been identified as important habitats for multiple stingray species, certain places like Port St Johns along the Wild Coast act as migratory highways for multiple species, and so much more.

Blue stingray. Photo © Alessandro De Maddalena | Shutterstock

Researchers have historically worked in silos, with very little collaboration, communication and connectivity between and amongst them. The only group that has generally had good communication over the years is the white shark group. This, however, is rapidly changing, with more collaboration than ever before. This is something that was also highlighted in the presentation – areas in which active collaboration can take place. Because telemetry is a fairly expensive game to play, especially for developing countries such as South Africa, pooling resources is a logical route to follow, especially if this leads to larger sample sizes, more students (which translates to capacity building and development) and long-term collaborations. For example, spotted gully sharks have been tagged by several research groups between 2016 and 2020. As little as six were tagged by some groups, with 14 being the most sharks tagged by another group. However, together 27 sharks were tagged, and pooling the data allowed for a better assessment of movement behaviour, and even led to some more interesting analyses like social networks – something difficult to do with a small sample size. Despite the immense progress made in this field of study over the past 25 or so years, this really is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of understanding the movements of sharks and rays along the South African coastline, something that we, the ATAP, hope to help with!