The soundscape of the Australian ghost sharks

The underwater world is far from silent: marine mammals, fish and invertebrates produce a whole range of sounds which can travel very far underwater. The other natural sounds come from the environment: rain, waves, earthquakes etc. Finally, sounds generated by human activities are becoming more and more prevalent: ships, seismic surveys, and construction work. Our oceans’ soundscape (the ‘landscape’ of sounds) has never been so noisy! And the noise has been shown to affect the behaviour and physiology of numerous fish species. However, almost nothing is known about the effect of noise on sharks and rays.

The Australian ghost shark travels into shallow waters to reproduce. Photo © Travis Dukta

Living in the deep sea, Australian ghost sharks are predicted to rely heavily on audition to navigate and find prey. One of our objectives is to record the soundscape of this species, especially when this species moves into shallow water to reproduce and lay its eggs. Nurseries of ghost sharks are rare, and we are lucky to be able to work in the Western Port and Port Phillip area in Victoria, Australia. We deploy sound recorders underwater to investigate the temporal and spatial dynamics of the nurseries’ soundscapes.

We can transform the recorded sounds into images, called spectrograms, to visually observe the patterns.

(Left) Lucille Chapuis deploying a sound recorder underwater. Photo © Hope Robins. (Right) Sound recorder deployed underwater to record the ambient soundscape. Photo © Lucille Chapuis

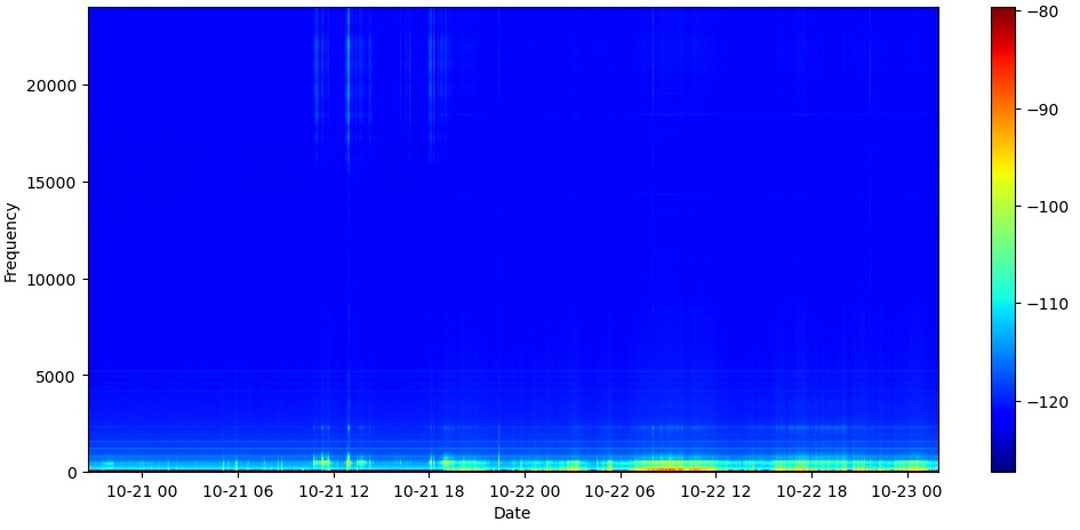

Here is an example of a spectrogram representing 48 hours of recordings in the shallow waters of a protected bay in Victoria, Australia.

Spectrogram of 48 h from a protected bay in Port Phillip, Australia. Graphic © Lucille Chapuis

It is relatively quiet, with low frequencies due to fish and invertebrates’ sounds. No boats can be heard.

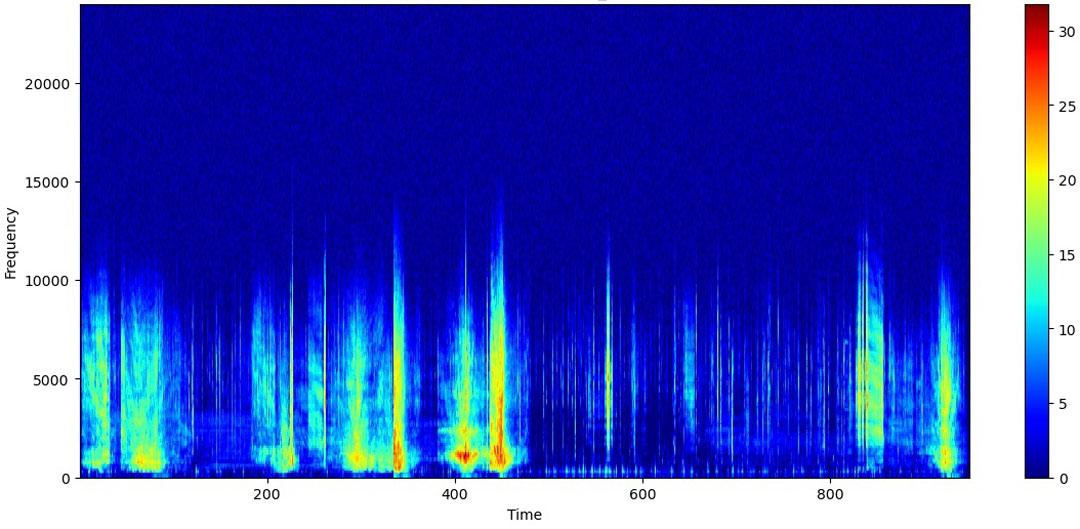

In comparison, here are just fifteen minutes of the recording set near a boat ramp in the same bay as before. A lot of boat passes can be heard.

Spectrogram 15 minutes from a non protected area, close to a boat ramp in Port Phillip, Australia. Graphic © Lucille Chapuis

Ocean soundscapes rapidly change due to increased human-made noise, which can profoundly affect marine animals. Recording the different soundscapes experienced by sharks and rays is an essential step to understanding their acoustic ecology and evaluating their vulnerability to noise pollution.