The Sargassum Struggle

Fieldwork is often romanticised — sunshine, salty air, a remote beach, and the thrill of discovery. As marine biologists, we know better. Behind many successful data points are battles against the elements, logistics, and unpredictable nature. During my most recent field trip to São Vicente Island in Cabo Verde, our team was reminded — yet again — that no matter how well you plan, nature always has the final word.

Our goal was straightforward in theory: catch and tag blackchin guitarfish (Latin name: Glaucostegus cemiculus) and collect tissue samples for genetic analyses. At the island of São Vicente these elusive rays are found just past the breakwater, close enough to target from shore using a single pole and line. It’s a simple but effective technique — one that has worked for our team in the past.

But this time, the ocean had other plans.

A blackchin guitarfish (Glaucostegus cemiculus) in the shallow waters of São Vicente, Cabo Verde. Photo © Stiven Pires | Biosfera 1 - Associação Ambientalista

Enter: Sargassum.

If you’ve ever tried fishing during a sargassum influx, you’ll understand the frustration that these floating masses of brown macroalgae can bring. Instead of guitarfish, our lines returned heavy with seaweed. Cast after cast, the floating mats of sargassum fouled our gear almost immediately. Lines tangled, hooks clogged, and any chance of reaching our target species vanished under a floating carpet of algae.

What was once a seasonal or occasional occurrence seems to have become increasingly common in Cabo Verde, according to locals from the NGO Biosfera, who have been working with our team conducting shark research since 2017.

I had heard about the sharp rise in sargassum blooms across the tropical Atlantic, forming what’s known as the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt. It seems that for coastal communities and marine researchers alike, the growing presence of sargassum is more than an inconvenience — it’s a developing ecological challenge with potential wide-reaching consequences. For example, sargassum washing ashore would have the ability to smother seagrass beds, coral reefs and mangroves, and could lead to hypoxic (low oxygen) conditions in shallow waters as it decomposes, killing and causing stress on the marine life in the shallows. For me, I wonder what kind of effect such blooms are having on the critically endangered blackchin guitarfish I’ve grown to know and love – a species already at risk of extinction due to anthropogenic impacts.

One of our tagging locations in São Vicente, Cabo Verde. What was once a pristine beach of white sand as far as the eye can see is now coated with mats of Sargassum that have drifted ashore. Photo © Kirsti Burnett

Sargassum at this scale isn’t just a nuisance and an ecological challenge — it’s a powerful barrier. Even a slight influx along the shore can make fishing virtually impossible. The breakwater zone, once teeming with potential to catch and tag sharks and rays — some species found almost nowhere else on the planet — became completely inaccessible.

Back in São Vicente, we waited. We cleaned lines. We tried different spots. But the sargassum held its ground.

As scientists, we pride ourselves on preparation — gear checks, protocols, contingency plans. But no amount of planning can change ocean currents. This was a harsh reminder that fieldwork isn’t just about adapting — sometimes it’s about accepting. When sargassum took over the shoreline in São Vicente, the only thing left to do (albeit, after the many failed attempts at fishing different locations and with different lines) was to step back and take a breath.

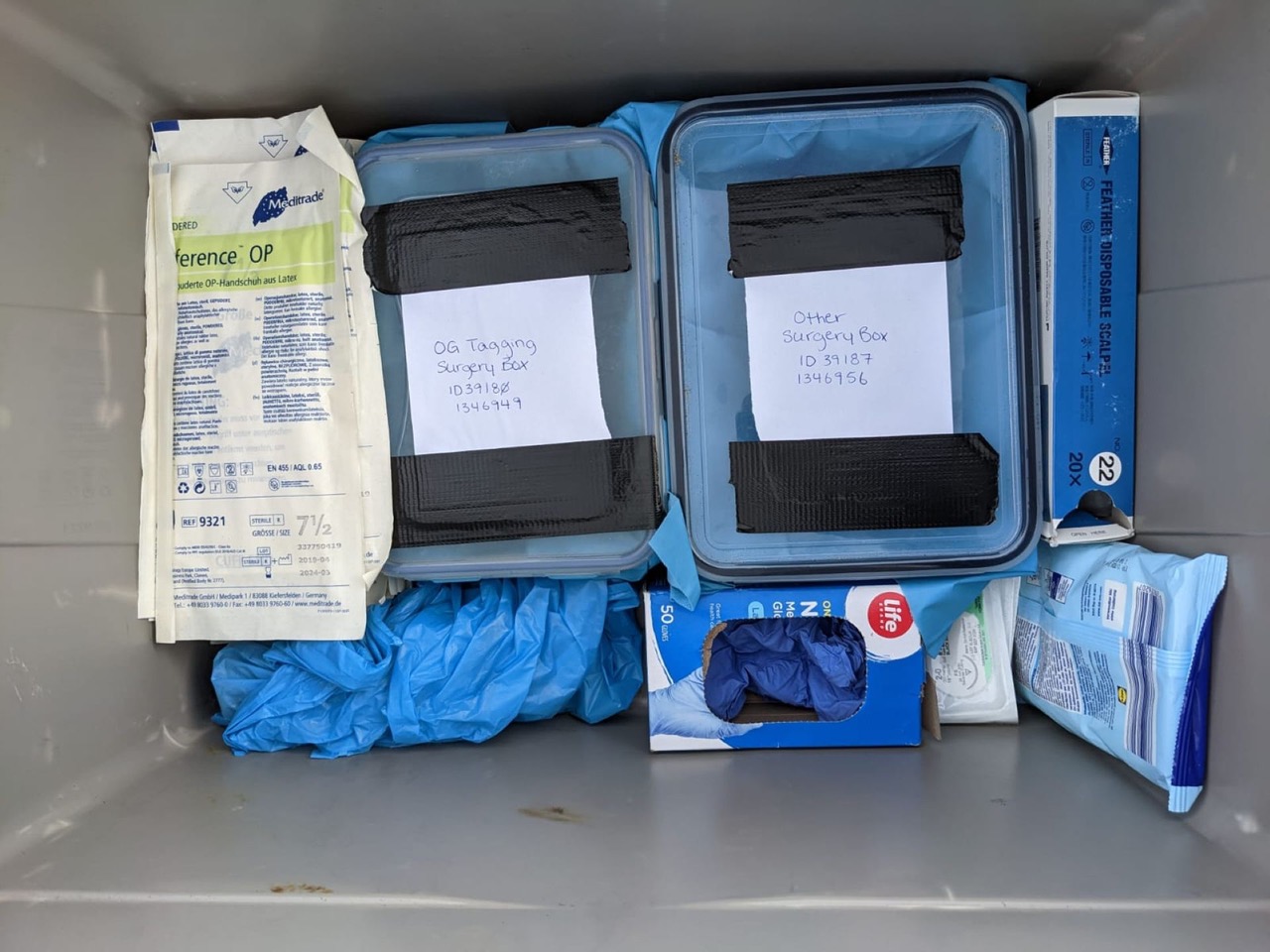

Surgical tagging equipment. Surgery boxes are equipped with sterile tags, surgical blades, and suturing gear, and sit on top of a surgical sterile towel drape to ensure our tagging procedure is done as surgically clean as possible while in the field. Photo © Kirsti Burnett

Despite the challenges, our time in São Vicente wasn’t wasted. Fieldwork always offers lessons, even when the data is sparse. We forged local connections and rekindled friendships, tried and refined our methods, and added another level to our understanding of the dynamic coastal environment blackchin guitarfish call home.

In marine conservation, success isn’t always measured in samples collected or tags deployed. Sometimes, it’s measured in resilience, patience, and the ability to keep showing up — even when all you catch is seaweed.