The Power of your Plate

I’m mid-sentence, my brain thrashing lamely with statistical terminology, when my cellphone vibrates loudly on the wooden desk. I should really switch this thing off for meetings. I toss the offending piece of technology into my bag and resume my discussion on our False Bay analysis, so it’s only later that I see the sms blinking innocently at me:

“Is red stumpnose on SASSI’s red list?”

Ah ha. My mother.

You see, I’d recently learned about a rather extraordinary fish we’d picked up in our BRUVs research in False Bay – and consequently shared its story with anyone willing to listen. This, inevitably, meant my conservation-minded mother.

Another beep from my cellphone and a second sms blinks at me, insistent now.

“They’re selling it at this restaurant and I’m concerned as to why …”

The Red Stumpnose from Lauren De Vos on Vimeo.

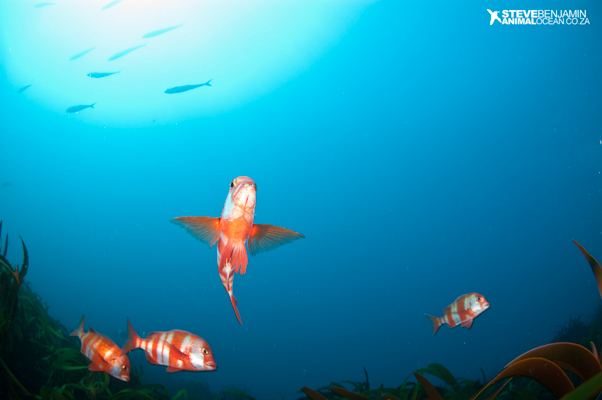

The red stumpnose (Chrysoblephus gibbiceps) is an endemic reef fish found only on South Africa’s reef systems. Their life history traits make them interesting to study, but highly susceptible to overfishing. We’ve recorded a few individuals on our BRUV research cameras in False Bay and Struisbaai

Now I’m no economist, but as an ecologist, I see life in linkages. We are trained to see life like this. We see the interdependence of species in their habitat. We measure the repercussions from minute actions that reverberate across ecosystems. This acute awareness of how life on earth is intricately linked, from species to species, follows directly through to the sustainability of our own species on this planet. So inevitably, a biologist’s work becomes increasingly about understanding this particular link: that between the biodiversity on this planet, and our place in it. We know that biodiversity conservation is, at its very core, less about the preservation of other species than it is about the sustenance of our own.

Professor and honorary curator of entomology at Harvard University, E.O. Wilson, puts it well: “Humanity is a biological species, living in a biological environment, because like all species, we are exquisitely adapted in everything: from our behaviour, to our genetics, to our physiology, to that particular environment in which we live. The earth is our home. Unless we preserve the rest of life, as a sacred duty, we will be endangering ourselves by destroying the home in which we evolved, and on which we completely depend.”

That most “scholastic-looking” fish, to borrow the words of naturalist and author Byden, makes for an interesting character in our unfolding False Bay story. Photo: Steve Benjamin

So the concept of repercussions is one I’m well familiar with, and it doesn’t take an ecologist (or an economist) to know that consumer choice is one of our most powerful tools if it’s positive repercussions we want to effect. There are, however, a great many of us who can see these linkages, an ability that is certainly not limited to trained scientists! This means, of course, that there are many South Africans who absolutely do care about making informed decisions when it comes to the fish they’re buying and eating. Our country’s savvy answer to providing committed, interested citizens with the tools to make informed consumer decisions lies in WWF’s Sustainable Seafood Initiative (SASSI) – and it’s a tool I refer to often when considering some of the species recorded on my BRUVs. In an age where information is increasingly freely available, ignorance, it would seem, can only now barely stagger to its feet as a rather weak excuse …

However, I often find that it takes some sort of personal connection to first open one’s eyes to these linkages and repercussions. If you’re not actively seeking out this information, it needs to come knocking on your door.

The distinctive red stumpnose wears bright, alternating stripes as a juvenile that fade as they grow older. Photo: James Bain

This story first came knocking on my own door courtesy of Megan Dawson, a colleague at the University of Cape Town. Megan has spent years studying the biology of this relatively under-researched species and was well-known (and well-loved!) in the small fishing town of Struisbaai – the core of red stumpnose distribution and the last stronghold of the population. Through conversations with Megan, I learned that old red stumpnose (an endemic reef fish, found only in South Africa) males develop a pronounced forehead, lending them a wonderfully cerebral air. A professorly-looking fish, if you will …

A candy-striped trail of tiny red stumpnose cruising through the kelp forests of False Bay – a hint of things to come, if we play our conservation cards right? Photo: James Bain

What had struck me, however, was the fact that these fish have declined so radically in my own research area, False Bay. From an assessment of historical catch data in False Bay, we’d seen that red stumpnose were caught in their hundreds decades ago – so why were they now on a conservation red list? According to the latest linefish assessment by Bruce Mann and researchers at the Oceanographic Research Institute (ORI), the red stumpnose is considered heavily overexploited.

I’d recorded my first red stumpnose on the BRUVs cameras last winter, and had filmed 4 individuals in the bay since then. 200 BRUVs hours and only 4 red stumpnose. We’d seen a few more juveniles while diving in False Bay – a heartening sign – but with the fishery open, the responsibility of choosing not to buy vulnerable species sits squarely with consumers.

Red stumpnose are bold rulers of the reefs of Struisbaai and on the Agulhas Banks. Photo: Steve Benjamin

Among Megan’s most important findings was that red stumpnose grow slooooowly. Her oldest specimen? 48 years old. Their diet of invertebrates – largely brittlestars and small crustaceans – means that it takes years for a red stumpnose to grow reasonably large, which has enormous implications for their breeding capacity. It’s a trait we see across a range of endemic reef fish that we monitor with our BRUVs, this susceptibility to overfishing because their life history traits (slow-growing, slow to reproduce, sex-changing, resident and often territorial) render their population less capable of “bouncing back” from heavy fishing pressure.

And herein lies the important information that we, as scientists, can relay to a wider audience. An anchovy is not a swordfish, which is not a red stumpnose – and consumer tools like SASSI are devised with this in mind: some species are more susceptible to fishing pressure than others. “A fish is a fish is a fish” is simply not true. Fisheries operate differently, are managed differently and deal with species with vastly differing biological traits. So, while fast-growing species might end up on the green list, one would think twice about buying a slow-growing, resident species.

Responsible consumerism, in my mind, is absolutely not about businesses closing their doors and rendering fishermen jobless. In fact, that scenario is precisely what it seeks to pre-empt. By way of explanation, I always think back to a paragraph in an essay I wrote during my MSc that explored the research of Kenneth Frank and his team of scientists at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography in Canada: “Nova Scotia, Canada in the 1990s. Oilskin-clad fishermen sit morosely on their weather-beaten vessels, out of work, with an industry that was their very livelihood in tatters. The eastern Scotian Shelf ecosystem that had been home to vast stocks of Canadian cod, around which a thriving commercial fishing industry had once been set up, had collapsed. Overfishing had driven these predatory fish to a population decline from which they were never to recover, despite the later desperate scramble to implement a moratorium on fishing and strict fishery regulations”.

The collapse of the cod fishery served as a wake-up call to remind us of the very real impact our consumption has on our oceans. In a world where fish remains a sought-after and important protein source, informed decision-making is our first line of defence. Responsible consumerism applies not only to the red stumpnose, of course, but finding a story to which we can relate makes its effects all the more tangible. If I’ve learned one thing from False Bay, it’s that taking an interest in species that may not have their own hit show on TV, but who end up on your plate with a side order of chips, holds rewards beyond the conservation of one species.

My advice? Dive in and discover some of the strange, shy or side-lined species of the sea – and understand what responsibilities lie within our grasp when it comes to determining their future which is, inevitably, linked to our own.