The Overview Effect

“The sea remains the greatest wilderness. To my mind, voyaging through wildernesses, be they full of woods or waves, is essential to the growth and maturity of the human spirit.” – Steven Callahan, Seventy-six Days Lost at Sea

I have to thank my friend Scott Ramsay from the Year in the Wild project (www.yearinthewild.com) for introducing me to Steven Callahan’s book, and leading me, inevitably, to this quote. Given my love of wild places, of introspection and of the “zoom in, zoom out” thinking typical of an ecologist, I think it’s an apt find that best describes the two years I’ve spent running this project. It also led me to muse on the past year’s travels, and more specifically, about learning and growth, the nature of sharing and the trajectory of marine conservation on our coastline (yes, well, I never was one for average daydreams …)

The sea is the wildest of places, even when it’s right on your doorstep or, like False Bay, hemmed in on either side by bustling city life. You need only spend one day bobbing at sea to realise just how far the ocean can transport you from the madness of life as a city-dwelling human-being.

That big, blue expanse beyond the shore. Sometimes tranquil, sometimes petulant and always alluring – learning to look at land from a seafarer’s point of view becomes undeniably addictive. Photo: Steve Benjamin.

The Overview Effect. It’s what they term the feeling astronauts describe when they’re staring back at earth from space and suddenly gain perspective of our fragile place is in this rather magical universe – and I’m of the firm opinion that we who work on the ocean experience much the same “zoomed out” view from sea. I’ve often, in the brief pause between lowering cameras, gazed back at land from where I sit, swaying, on the sea’s shimmering surface.

It’s quiet out there.

Save for the grumpy croak of a petrel, or the squawk of a seagull wheeling above you (eyeing our bucket of pilchards, no doubt), there’s a certain stillness that heightens your awareness: of the salt crusting your eyelashes, of the sunshine warming your shoulders (that’ll be yet another dusting of freckles, you realise with a sigh …) and of the waves lapping the boat’s hull.

Slap. Slap. Slap.

Cape Nature Stilbaai’s patrol vessel, Nkwazi, pauses for a moment while Jean du Plessis (MPA manager) and Wayne Meyer (marine ranger, Goukamma) work with me to deploy BRUVs. I journeyed back to Stilbaai to monitor the new BRUVs system in place there. Photo: Steve Benjamin.

If anything, two years of fieldwork teaches patience. In between the flurry of datasheets, the skipper’s voice calling out GPS coordinates and the laughter that seemed such a permanent feature of the hours our BRUVs team spent at sea, you learn to be still. To listen, intently: for the pffffffffft blow of a Bryde’s whale as it rises to breathe not far from your boat, or the sigh of a seal come to investigate your presence. Time in wilderness, out on the ocean, becomes almost entirely about the animals who call this ecosystem home. Every thought is dominated by the creatures you record on your BRUVs, the ocean visitors to our boat as we float out at sea and the species you hope to someday see recover in the regions where you work. So how on earth did last year become, for a biologist, so much about the people I worked with?

Jean prepares to launch patrol vessel Nkwazi into the Stilbaai MPA, and I keep an eye on the BRUVs … Photo: Steve Benjamin.

The answer to that, I suppose, lies in my understanding of the “growth and maturity” that Callahan mentions in the opening quote. Wilderness has not only taught me many a lesson in respect and maintaining a child-like sense of wonder, but has introduced me to a host of teachers with whom I worked these past two years. I might have arrived as the eager academic in this equation, clutching my papers and my questions and my theories, but my true education came from learning to listen. My personal experience of the overview effect? Gaining perspective of what is happening, conservation-wise, on our vexingly complicated, enchantingly fragile and hopelessly alluring coastline. What started off as a year of training that I was providing for rangers and managers along the coast turned into an information sharing experience that challenged my preconceptions about marine conservation on this coastline and forced me to listen.

Yes.

That same, patient listening I’d spent hours practising at sea as I silently willed a whale to surface somewhere nearby, if only to break the monotony of a deployment period. That same, intent listening I’d learned was vital in respecting the ocean’s ever changing moods – head cocked, senses alert to perceive a shift in the wind speed or a sudden snarl from our boat’s engine. Wilderness teaches you that listening is a skill you develop, something that you practice over, and over, and over …

And I believe that there is something in the willingness to listen that encourages humility and gently commands respect, which, in the world of conservation, I simply cannot imagine us succeeding without.

Working with a like-minded team at sea is more peaceful than you’d think: Jean, Wayne and I work together to deploy BRUVs as Lee Otten films for a local conservation TV programme 50/50. Photo: Steve Benjamin.

If the BRUVs project has been an exercise in effective translation and communication, what can I show for my practice sessions in listening, and learning … and sharing? Well, I’m only too chuffed to announce that Jean du Plessis and his indomitable team have completed their first GoPro BRUVs survey of the Stilbaai MPA. I visited them at the end of last year to check their systems, and came home having taken a few notes on some innovations they’d added to our design. I’ve peppered this blog post with photos from that expedition – exciting evidence, I believe, of what phenomenal potential this little reserve has to offer.

Keith Spencer and his Cape Nature team at Goukamma MPA finished their first GoPro BRUVs survey midway through last year – just before an oil tanker slammed into their shores, spilling its cargo into their waters and testing their team’s mettle to the very core in the clean-up operations that followed. Among the exciting finds that marine ranger Wayne Meyer has been keeping me updated with? A recording of humpback whale songs on their BRUVs as these nomads charted their course through Goukamma’s protected waters …

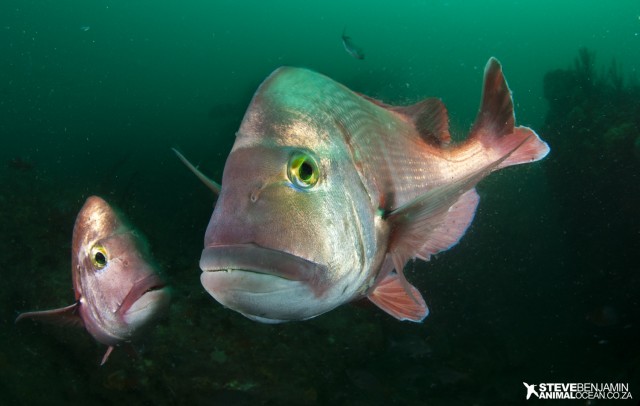

The protection of vulnerable reef fish in the Stilbaai MPA is essential to maintain sustainable fisheries on South Africa’s coast – and a healthy ocean ecosystem. Photo: Steve Benjamin.

Not one to be left behind, Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife has assembled a team of perhaps the most frighteningly capable women I’ve ever encountered. Jennifer, Tamsyn and Jean are leading the charge on a section of South Africa’s coast where the raging Agulhas current tests the ingenuity of every scientist working in her waters. I cannot wait to receive a first glimpse of the footage they retrieve, to piece it together with the magical records Bruce Mann and his team at the Oceanographic Research Institute are sharing from the Pondoland coast (follow Jade Magg’s reports on their work here: http://www.seaworld.org.za/research/entry/bruv-new-insight-into-offshore-reef-marine-life).

So I find it startling that people still ask me whether I ever feel disheartened working in the field of conservation. Whether I feel, at the ripe old age of 25, that I’m heading down a dead-end street.

I usually pause for dramatic effect before shaking my head. Emphatically.

I can never quite articulate why exactly it is that I feel this way, but I suspect it’s got something to do with the way wilderness has led me to learn about connectedness.

I take great comfort in the knowledge that I do not work alone. I still marvel each morning that I am part of a team of people who are willing to sit together, listening and sharing, to figure out how best we can address the challenges we face, together, on this coast.

It’s good to know this is what we’re working for: the recovery of species impacted by fishing pressure on our coastline. Photo: Steve Benjamin.

In a strange way, it was through wilderness that I truly learned about the “human spirit” and what it is capable of achieving. And again, it’s Steven Callahan who says it best: “The sea that tested me also proved forgiving enough to let me live, to show me how to live. For the first time in my life I felt truly humbled. It is just another irony with which my tale is filled – the heartfelt realization of one’s insignificance yields a calming sense of being completely connected to the greater whole. As a tiny part of the world and humanity, I now feel more at peace and much larger than I ever felt as a man alone”.

So, as I prepare to head up the coast again in a few weeks’ time: this time, to present at the WWF MPA Forum, then on to work with Eastern Cape Parks, and to connect with SANParks on the Garden Route and the Nature’s Valley Conservation Trust, I actually have to take my hat off to all the people I’ve worked with and who are so successfully initiating their own BRUVs projects along the coast.

Thank you, I suppose, for listening.