The magic of mangroves

In amongst a mangrove forest, it’s easy to get lost in the magic of it all. The stillness of the thick, humid air, rich with that earthy after-rain smell; the vivid greens of the thick waxy leaves. As you’re engulfed by birdsong and insects chirping, even the buzz of mosquitos is somewhat serene. Below the glossy and tranquil waterline, colours burst through dull roots: brightly striped parrotfish, intricately patterned grunts, the deep hues of mangrove snapper.

Mangroves are a key habitat in the Bimini ecosystem, their productivity demonstrated by a high density and diversity of fishes. Photo © Matthew D. Potensky.

It is no coincidence that mangrove forests feel like a full immersion in nature. Together with the likes of coral reefs and tropical rainforests, they are one of the most biodiverse habitats on earth: you can swim alongside baby sharks, spot seahorses and may even be lucky enough to share your space with manatees. The distinctive tangled root systems provide protection to small animals by being impassable to larger predators, and in doing so act as important nursery grounds for some species of reef fish, sharks and crustaceans during the crucial early stages of development. Above the waterline, leafy mangrove trees provide habitat for migratory birds, and can also be home to snakes, lizards and insects.

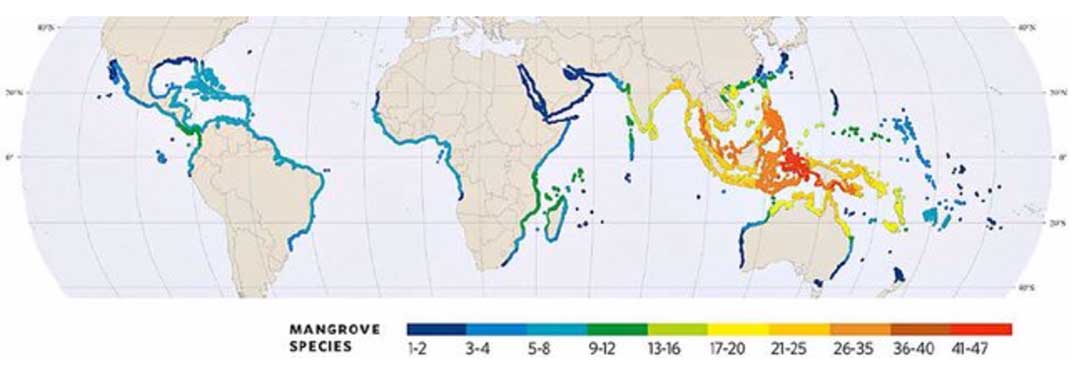

The trees themselves are from a group of 75 highly salt-tolerant species, distributed worldwide along tropical and subtropical coastlines. Mangroves are easily recognisable by their enchanting, tangled roots that, alongside their role as a nursery, also play a crucial role in the regulation of oxygen and salt that is fundamental to plant respiration and survival in extreme tidal zones. The highest density and diversity of mangroves occur throughout Southeast Asia, while in Bimini and the wider Bahamas only four species occur: red, black, white and buttonwood mangroves. These species form most of the coastal habitat around the islands of Bimini, with the most significant forest occupying the entire eastern peninsula of the north island forming an area locally known as East Wells.

Despite having a relatively low plant diversity, the biodiversity of the occupants of Bimini’s mangroves is rich, as described in a survey conducted by Steve Newman in 2003. Between the two islands of Bimini, 153 species of fish alone were identified in the mangrove communities. Further, small juveniles were sampled from all of the families present, confirming the importance of Bimini’s mangroves for the life cycle of many species and recruitment of fish onto coral reefs. One of the most common fish found in these surveys was the yellowfin mojarra – the favoured prey of lemon sharks. We know that the juvenile lemon shark presence is linked to the safety and the prey abundance in the mangroves and nearby shallow water seagrass beds. So not only are these habitats important for the species within but also form a crucial part of Bimini’s wider food web.

Studies conducted by the Sharklab over the past 30yrs have further uncovered some of the more intricate ways that mangroves are important for juvenile lemon sharks. In a fascinating 2012 paper from Tristan Guttridge and colleagues, mangrove inlets were shown to be used by sharks for safety. Amazingly, utilisation of mangrove refuge areas was directly related to the amount of danger each shark was in: smaller, more vulnerable sharks used the refuges more often and for longer periods of time, and refuge use was highest during high-tide, when large predators can come closest to the mangrove edges. Therefore, the presence of these inlets around Bimini are likely providing valuable refuge during the most dangerous time of the day, and in doing so allow greater survival of the lemon shark population at a key life stage.

Proportion of times visited, mean duration of visits and time to high tide at the exit from mangrove refuges by juvenile lemon sharks. (from: Guttridge et al. 2012).

Beyond providing habitat, security and food sources, mangroves provide myriad ecosystem services. Mangrove roots increase the stability of the soft coastal soils that are otherwise vulnerable to erosion. They also absorb tremendous amounts of wind and wave energy to protect inland areas from storms and hurricanes, which is pertinent in countries like The Bahamas that stand in the path of many Atlantic storms. They also act as carbon sinks, effectively capturing and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide, and maintain local water quality by acting as a biofilter, taking up excess nutrients and pollutants in the surrounding water.

Globally, mangrove loss is occurring rapidly, with less of half of historic global mangrove cover remaining today. Often considered as unimportant swamp land by developers, the removal of mangrove to facilitate shrimp farming, oil extraction, urban expansion and building of tourist facilities threaten these coastal habitats. The knock-on effects of this deforestation include decline in local fish population, degradation of water quality, coastal erosion and the release of atmospheric carbon dioxide, which contributes to global warming. This feeds back into further threats, such as sea level rise, which exacerbate the existing threats to mangrove survival and biodiversity. Beyond losing the forests themselves, the necessity of mangroves for the juvenile life stages of populations also threatens the wider biodiversity of marine ecosystems, including coral reefs, and the foundation of the western Atlantic lemon shark population.

Continued research to support policy recommendations to protect mangroves are vital to their protection and restoration, as well as conserving the biodiversity within. While we continue to research and communicate the importance of mangroves at the Bimini Sharklab, projects and organisations that are completely devoting resources to do so also include the Mangrove Action Project, Waterkeepers Bahamas, Save The Bays, and initiatives from the Bahamas National Trust.

So, while they may not be as obviously attractive as the Great Barrier Reef, or instantly captivating as the Amazon, reserve a part your wonder for the complex marvel that are mangroves. And if you ever get the chance to experience them up close, I can promise you’ll find them as spellbinding as we do.

References and resources:

Newman, Handy and Gruber (2003) Spatial and temporal variations in mangrove and seagrass faunal communities at Bimini, Bahamas. Bulletin of Marine Science. 80(3); p529-553.

Guttridge et al. (2012) Deep danger: intra-specific predation risk influences habitat use and aggregation formation of juvenile lemon sharks Negaprion brevirostris. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 445; p279-291.