The little leopard catshark that could

Good things come to those who wait. If you venture underwater and swim around a reef, you’re undoubtedly bound to see some incredible things, including animals of a shyer nature – the catsharks. Not much is known about these small shark species, and the majority of those found in South Africa are endemic, being found nowhere else in the world.

Pyjama catsharks in False bay, South Africa. Photo Mac Stone | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Ralph Watson, a marine biologist with the Dyer Island Conservation Trust, embarked on a PhD journey at Rhodes University, specifically aiming to learn more about the movement behaviour of two different co-existing catsharks – the pyjama catshark (Poroderma africanum) and leopard catshark (P. pantherinum). In late 2015 and early 2016, 11 pyjama catsharks and 10 leopard catsharks were tagged in Mossel Bay, Western Cape, with tags having an expected battery life of 3 years. Firstly, among all the sharks detected, they accumulated more than 160 000 detections. Secondly, the movements of these sharks were detected, on average, for 2.5 years. All except one lonely male leopard catshark, which was tagged in May 2016, and by hook or by crook, it is still being detected, more than 5 years later! For this reason, he’s been dubbed “Lucky”.

This particular animal was tagged close to the town of Mossel Bay, and for the most part, hung around for the majority of the study period (2016 – 2019). This just shows how resident this species is, with Lucky returning to his home-reef whenever he briefly ventured away. However, the study came to an end, but Lucky’s tag didn’t, and with receivers still in the water as part of the greater Acoustic Tracking Array Platform, data kept on being collected.

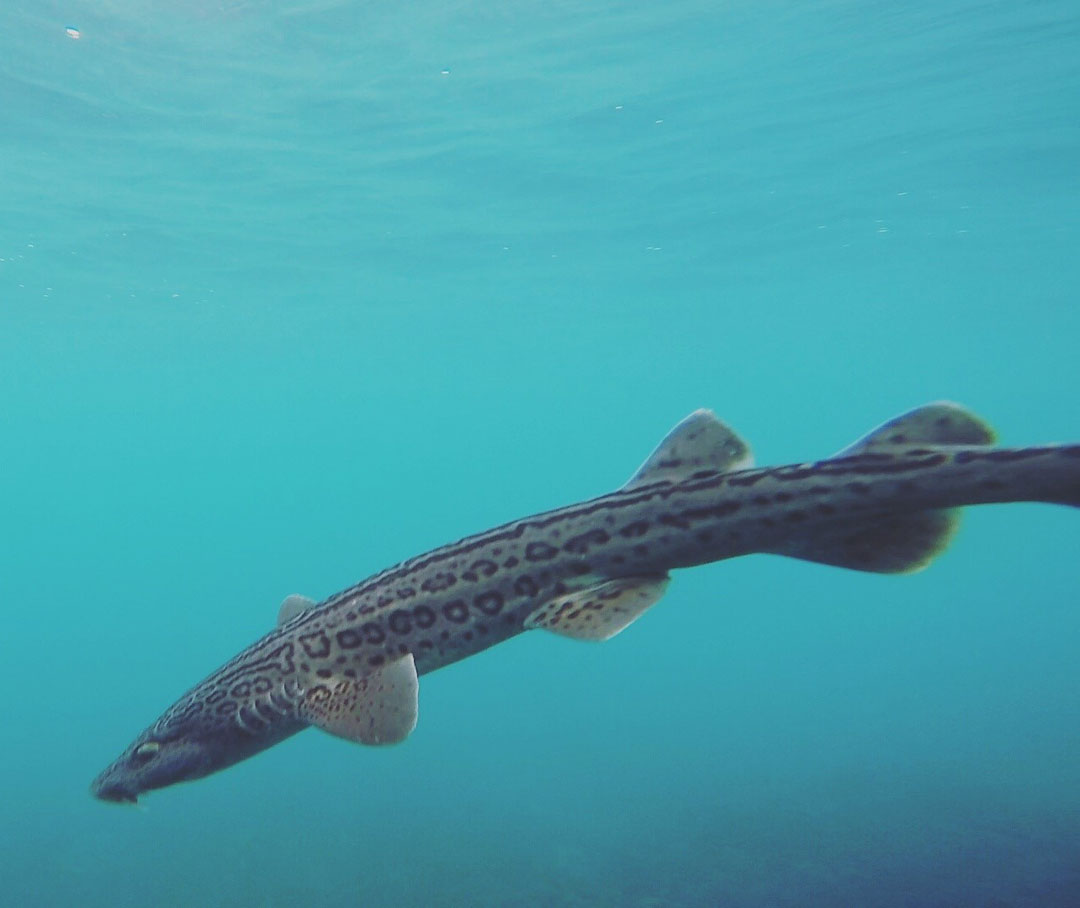

'Lucky' the leopard catshark. Photo © Esther Jacobs.

The reason why the tag keeps on pinging is unknown. However, all the tags that were used are handcrafted by specialists overseas in Canada. Extra care is provided to make sure there are no faults in the tag that may result in the tag stopping prematurely. However, errors can always creep in, and luckily for us, it caused the tag to keep on pinging way after its lifespan.

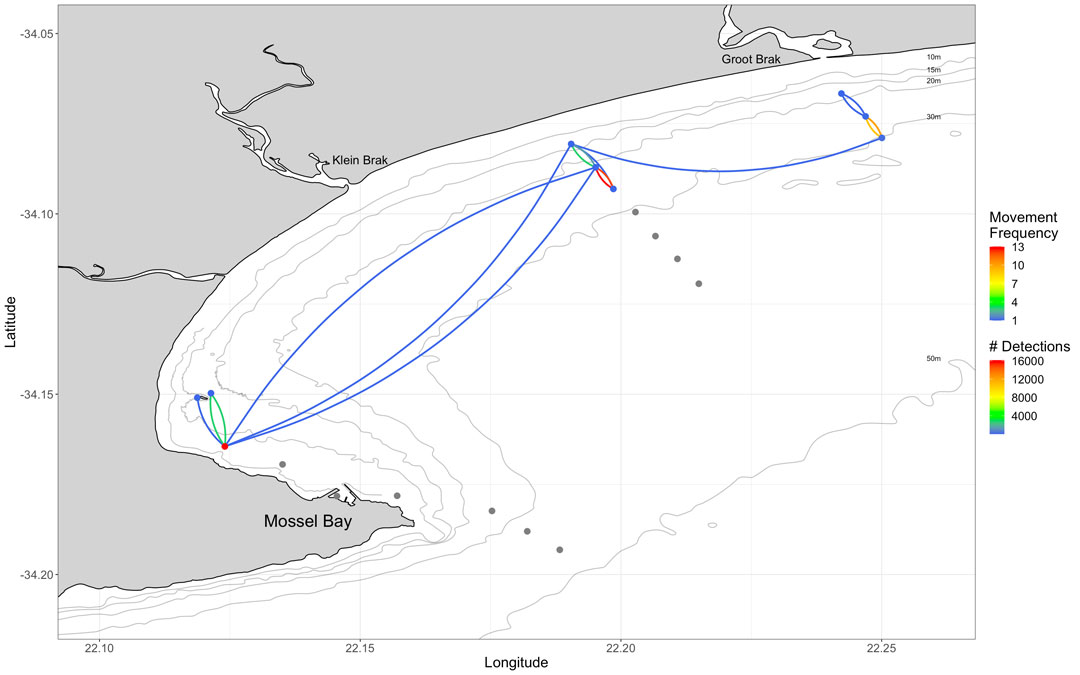

It’s now almost 5 years since the animal was tagged and it looks like in that time, Lucky decided to relocate. We’re not talking hundreds or thousands of kilometres, but a mere handful, which in catshark terms is more or less considered to be average (although the maximum distance moved collected via dart tagging as part of the Oceanographic Research Institute’s Cooperative Fish Tagging Project is an incredible 722 km!). In early 2018, the little-leopard-catshark-that-could moved from his home at Roman’s Reef across the bay to Klein Brak (approximately 11 km east), before moving on to Groot Brak in late 2018 (approximately another 5 km east), where a large reef system is located.

Map depicting Lucky's movements.

Interestingly, it appears that Lucky only stayed in waters shallower than 30 m. This has consequences for its conservation, as a large per cent of recreational fishing occurs in shallower waters. If it spends its whole life in heavily fished areas, it puts a serious strain on its chances of survival. This is even more of a concern in animals that are, in all likelihood, still immature, which is more than likely the case with Lucky. Leopard catsharks reach 50% maturity at 61 to 77 cm total length (TL); Lucky was only 58 cm TL at tagging, therefore, he may have reached maturity in the five years that he has been monitored. As such, these rare occurrences of extended tag longevity provide incredible opportunities to collect potentially unknown information. For example, we would never have known that Lucky relocated his home if it wasn’t for those additional years monitored. Here’s to future glitches in technology and all the additional information collected!