The Guitarfishes and Wedge Fish Diaries of Somanga: Science, Fishers, and the Fight for Sustainability

Boats moored at a Somanga landing site, Kilwa District, Tanzania. Photo © TAFIRI field team

Where science meets the sea

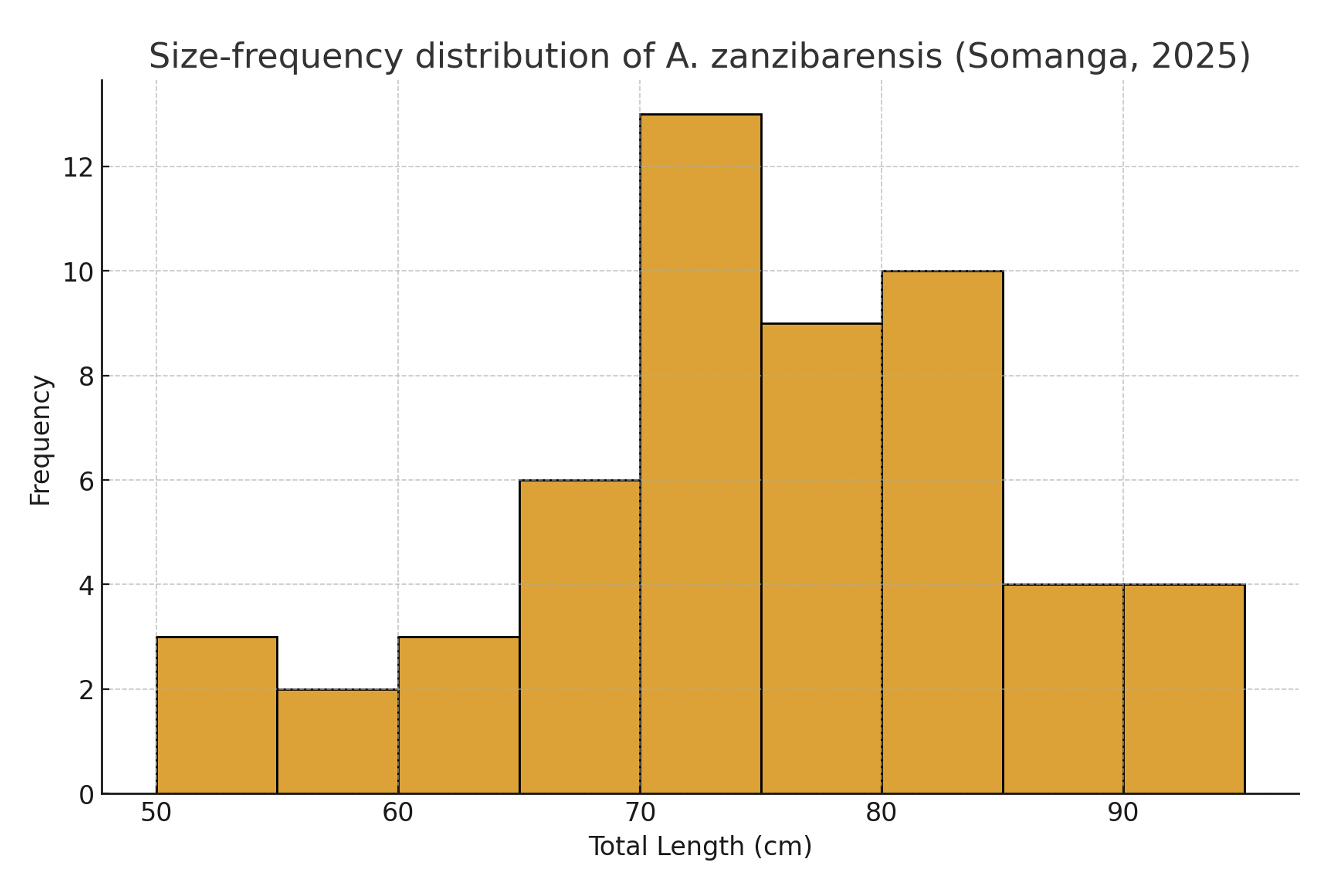

The Somanga coast of southern Tanzania may look calm, but beneath the waves lies a story about one of the Western Indian Ocean’s endemics and a very rare species with an extremely restricted range, and it is threatened by local fishing activities: the Zanzibar guitarfish (Acroteriobatus zanzibarensis). Between June and September 2025, my team and I recorded 56 individuals landed at Somanga landing site — each one a clue in understanding how this endemic ray species is coping with fishing pressure.

These observations mark a vital step in documenting the population status of this fish. And, as we discovered, the patterns emerging from Somanga’s shores speak volumes about both the resilience and vulnerability of Tanzania’s coastal ecosystems.

Acroteriobatus zanzibarensis photographed in Kilwa. Photos © Bigeyo Kuboja

A closer look beneath the surface

Most of the A. zanzibarensis we measured fell between 65–85 cm total length, with few very large individuals. This suggests the fishery is harvesting mostly sub-adults—young, growing fish that haven’t yet reached full maturity. Catches were also male-biased (2.18:1), a pattern that could be shaped by gear type or behaviour differences between sexes.

When we applied a Length-Based Spawning Potential Ratio (LB-SPR) model — a tool used to gauge how much breeding potential remains in a stock — the results showed an SPR around 0.32. That’s below the sustainability target (0.40) but still above the danger limit (0.20), meaning the stock is under moderate fishing pressure and could tip toward recruitment overfishing if unmanaged.

Size-frequency distribution of Zanzibar guitarfish (Acroteriobatus zanzibarensis) landed at Somanga between June–September 2025. Figure © TAFIRI 2025

A shared coastline, shared challenges

The Somanga fishery doesn’t only land guitarfishes. In the same months, we also recorded Rhynchobatus australiae, a wedgefish species reaching up to 2.9 metres. These giants—known locally as papa charawanzi—play a critical role in coastal ecology but face high demand for their fins and meat. Our monitoring showed few large breeding females, another signal of overexploitation risk.

Data from Somanga revealed that the fishery interacts with multiple life stages of R. australiae—from juveniles and subadults to large adults—suggesting overlap between fishing and nursery grounds. Mid-sized individuals dominated the catch, while large reproductive females were scarce, indicating selective fishing pressure that threatens breeding potential. The Length-Based Spawning Potential Ratio (LB-SPR) model estimated the stock’s spawning potential at only 15–25%, well below the 20% threshold for sustainability. These findings point to recruitment overfishing risk and emphasize the need for management actions such as protecting large females, reducing juvenile bycatch, and introducing seasonal or gear restrictions to safeguard the species and align with Tanzania’s national and CITES conservation commitments.

Rhynchobatus australiae landed in Kilwa. Photo © Bigeyo Kunoja

A Rhynchobatus australiae caught in Liwa. Photo © Bigeyo Kunoja

Two Rhynchobatus australiae individuals landed in Kilwa. Photo © Bigeyo Kuboja

From Data to Maps: Tracing the Fishing Footprints of Somanga

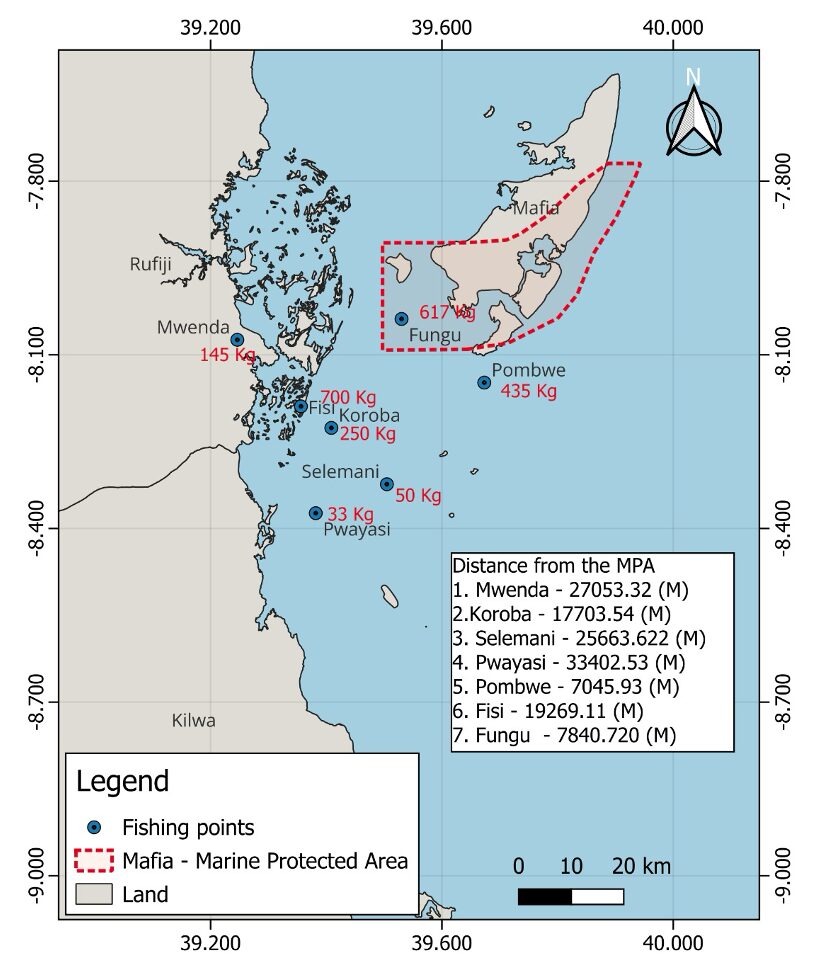

Spatial data collected from GPS-equipped skippers revealed seven main fishing grounds — Fisi, Pombwe, Fungu, Mwenda, Koroba, Selemani, and Pwayasi — some just a few kilometres from the Mafia Marine Protected Area (MPA) boundary. The richest catches were near Fisi (700 kg) and Pombwe (435 kg), suggesting spillover from the MPA could be supporting local fishers. These maps now provide valuable, real-world data for Tanzania’s Marine Spatial Planning and GBF Target 3 (30×30) implementation.

Spatial distribution of Somanga fishing grounds, showing proximity to the Mafia MPA boundary. Map © TAFIRI GIS Unit

Why this matters

For me, what stands out most about Somanga isn’t just the numbers — it’s the people. Local fishers, many of whom I’ve known for years, are the custodians of this living data. Their knowledge and willingness to log catches using GPS devices are helping to build Tanzania’s first spatially explicit shark and ray database.

These collaborations show how science, local knowledge, and conservation can come together. Identifying hotspots for guitarfishes and wedgefishes, we can guide adaptive management — protecting nursery areas, adjusting gear use, and ensuring these species continue to glide through Tanzanian waters for generations to come.

Boats moored at a Somanga landing site, Kilwa District, Tanzania. Photo © TAFIRI field team

In reflection

From Zanzibar guitarfish to wedgefish giants, Somanga’s story is one of discovery and responsibility. As we map fishing grounds, monitor catches, and work with coastal communities, we are piecing together the puzzle of how Tanzania’s reefs and rays can thrive side by side with sustainable livelihoods.