The enigmatic ears of sharks and rays

Like all fishes, sharks and rays have ears: a small opening on each side of the head leads directly to an inner ear inside their cranium, invisible from the outside. Sounds underwater are particularly efficient: they travel faster and further than in the air. Therefore, sharks probably tune in to the ‘soundscape’, combining all sounds in their environment to navigate underwater and listen to their prey.

The brain and inner ears of the Australia ghost shark, dissected out by Hope Robins. Photo © Hope Robins

We are trying to understand more about how their hearing works, and for this reason, we investigate the morphology of the ear. We can dissect the structure out of animals caught via by-catch to observe it: both ears are complex 3D structures closely attached to the animal’s brain and require fine dissecting skills!

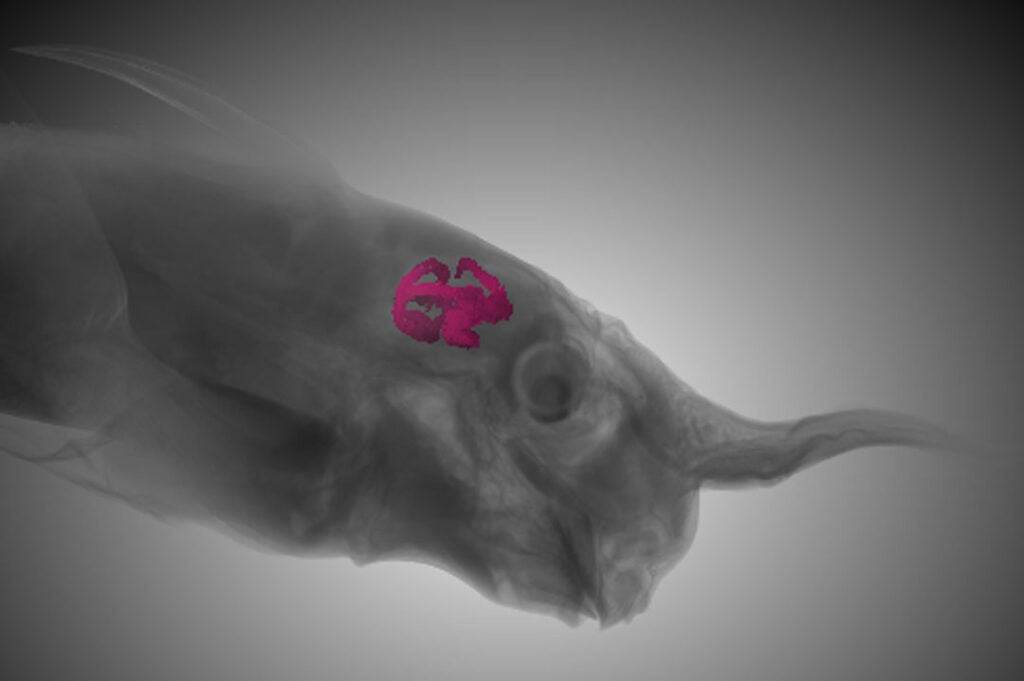

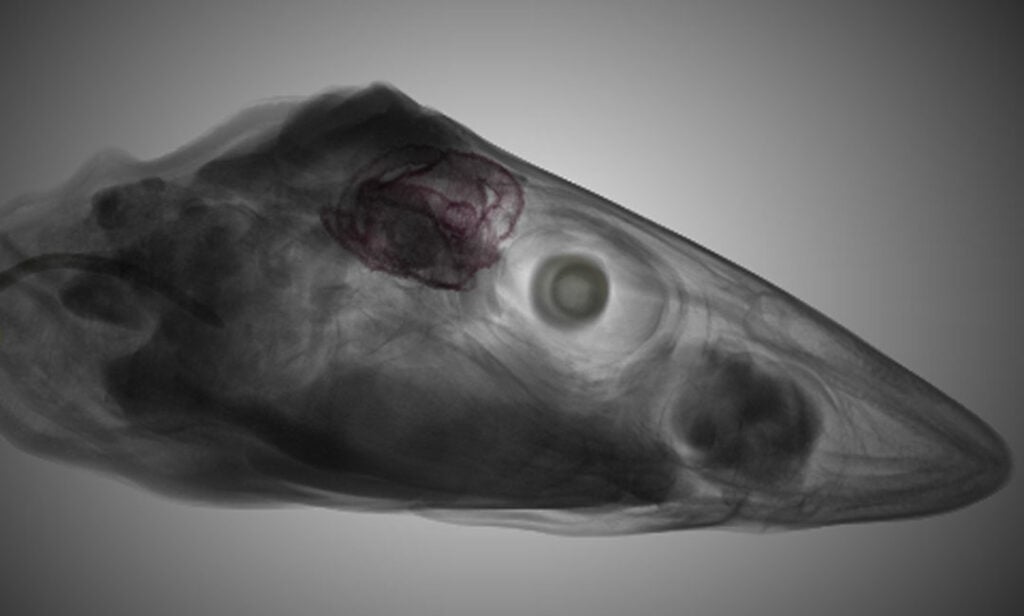

But we can also use bioimaging techniques which allow us to directly visualise the ear and the brain inside the cranium. We use computerised tomography (CT) scanner that combines a series of X-ray images taken from different angles around the shark’s head.

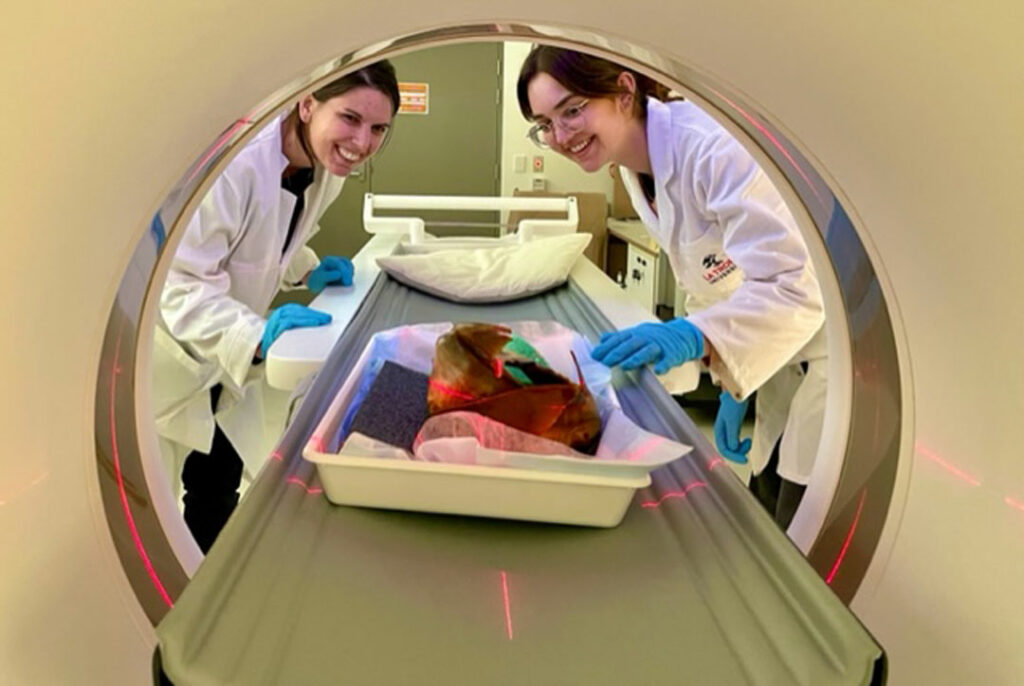

Lucille Chapuis and Hope Robins at a CT scan facility, about to scan the body of a preserved Australian ghost shark. Photo © Jenna Crowe-Riddell

CT scan of the Narrownose chimaera, with the right inner ear segmented. Morphosource © Lucille Chapuis

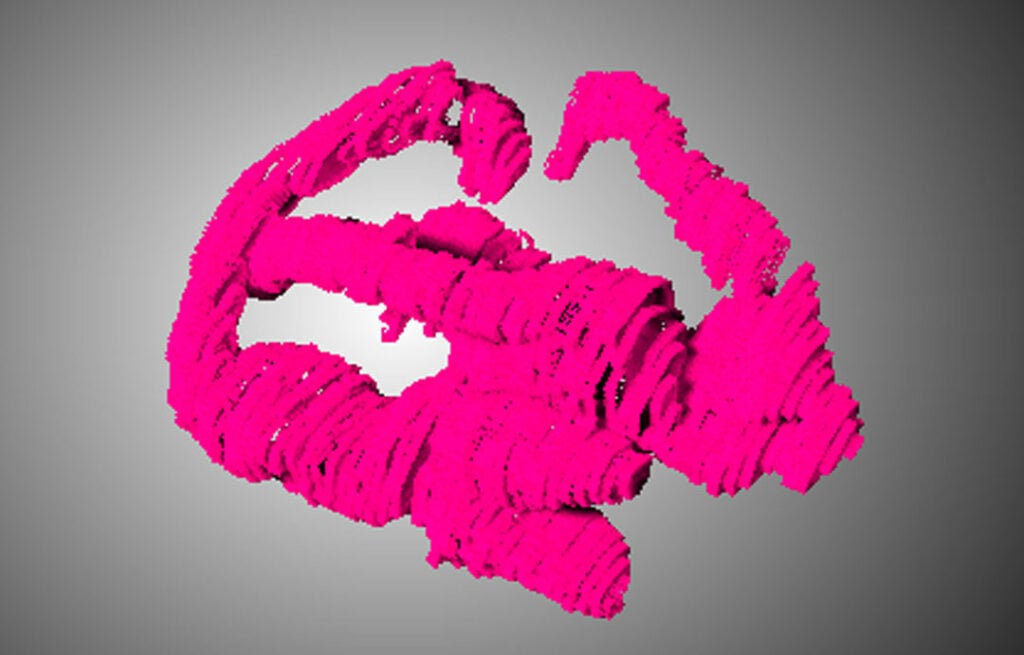

3D segmentation of the Narrownose chimaera inner ear. Morphosource © Lucille Chapuis

CT scan of the Gummy shark, showing the inner ear in purple behind the eyes. Photo © Hope Robins and Lucille Chapuis.

The 3D models of the ears within the shark’s head allow us to measure their relative size. We can then compare different species of sharks and rays. We have found that this group of animals shows an especially high diversity of ear shapes and sizes. This is maybe related to the very diverse environments that different species of sharks and rays occupy in all oceans of the planet. More investigations are needed to understand fully what the drivers of this diversity are and how the inner ear of sharks and rays work to detect sound underwater.