The Azores Archipelago: A Refuge for Oceanic Elasmobranchs

Located along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the North Atlantic, Faial is one of nine islands that make up the Azores Archipelago. The region contains unique oceanography that is influenced by the Gulf Stream, creating a hotspot for marine life and a critical stop for marine organisms, including migratory elasmobranchs. The archipelago is an important fringe habitat for endangered species such as the sickelfin devil-ray, Mobula tarapacana, and whale shark, Rhincodon typus, by supporting prominent seasonal aggregations that are predicted to become increasingly important for the species in response to climate induced environmental changes [1] [2]. Heavily exploited species such as the near threatened blue shark, prionace glauca, and endangered shortfin mako shark, Isurus oxyrinchus, are also commonly found in the region [3][1]. Additionally, the archipelago contains important habitat areas for juvenile smooth hammerheads, Sphyrna zygaena, (global population listed as vulnerable by the IUCN) and tope sharks, Galeorhinus galeus, which are listed as critically endangered by the IUCN [1]. This is just the tip of the iceberg as the Archipelago is also home to a wide range of deep-sea species, including the bluntnose sixgill, Hexanchus griseus [1].

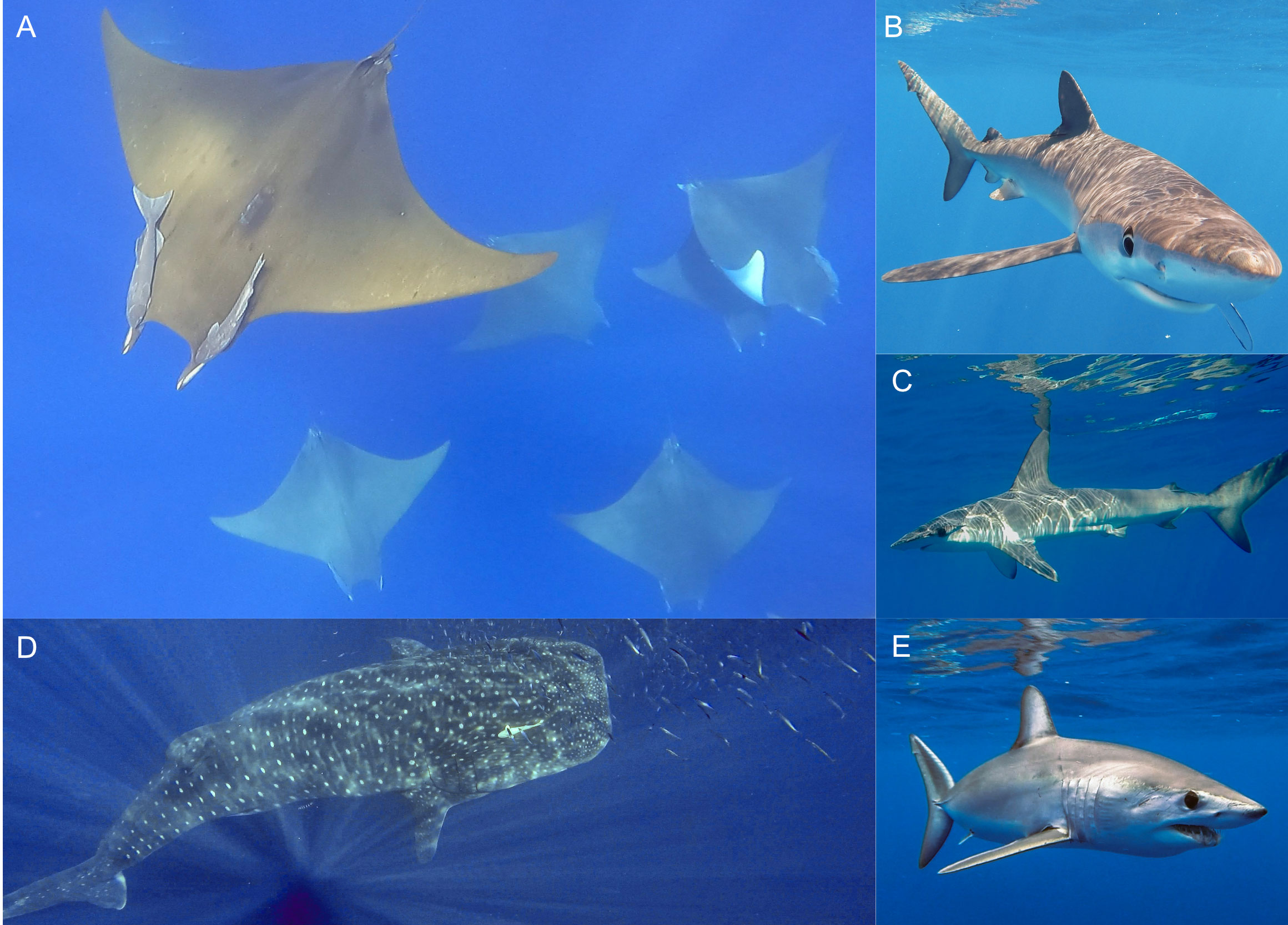

Figure 1. Collage of easmobranchs frequently encountered within the Azores Archipelago; A) school of sicklefin devil-rays, Mobula tarapacana; B) blue shark, prionace glauca; C) juvenile smooth hammerhead, Sphyrna zygaena; D) whale shark, Rinchodon typus; and E) a juvenile shortfin mako shark, Isurus oxyrinchus. All images © Sophie Prendergast

Although some conservation efforts have been implemented across the islands, additional information is needed to support supplementary management and conservation for many of the species that utilize the region. However, before more conservation strategies can be implemented it is essential to develop a complete understanding of how, when, where, and why these elasmobranchs utilize the different habitats within the Azores. The EcoDivePWN team, led by Dr. Jorge Fontes, specializes in elasmobranch movement ecology and utilizes a wide range of novel bio-logging technologies to investigate the mechanistic drivers of elasmobranch distribution in the region. You can find more information about Jorge’s project about whale shark and tuna feeding associations here, https://saveourseas.com/project-leader/jorge-miguel-rodrigues-fontes/.

Figure 2. Image A: Dr. Jorge Fontes, Team Lead and Research Associate at the Okeanos Institute – University of the Azores (image © the BBC); Image B: Dr. Bruno Macena, Post Doctoral Researcher (image © Bruno Macena); Image C: from left to right: Andrea Herrera (Intern), Diya Das (PhD student), Sophie Prendergast (PhD student & PI of the SOSF sicklefin devil-ray project), Bruno Saraiva (PhD student), Francisco Serra (Intern), and in the center is Robert Preister (PhD student; image © Andrea Herrera)

For example, my PhD investigates the interface between behavior and physiology of blue sharks, Prionace glauca, and sicklefin devil rays, Mobula tarapacana. For this we use a combination of purpose designed bio-logging tags and traditional satellite tags to investigate how temperature influences the 3-dimensional distribution of these two contrasting, yet spatially overlapping, species. However, temperature is just one of many environmental factors that influence the species’ movement patterns. PhD student Bruno Saraiva is working to determine if and the extent to which sicklefin devil-rays and whale sharks utilize the deep scattering layer for foraging. Diya Das (PhD student) studies the orientation and navigation cues used by migratory elasmobranchs around open ocean volcanic islands. Lastly, Robert Preister (PhD Student) investigates the importance of ocean island habitats as elasmobranch nurseries. You can find out more about the team’s projects at https://okeanos.uac.pt/team.

Figure 3. Image A: Map of the Azores Archipelago in relation to the greater North Atlantic; Image B: Map of the Azores Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ, outlined in orange) highlighting the regions unique bathymetric landscape and the existing marine protected areas (MPA’s, outlined in pink) within the Azores Exclusive Economic Zone. Image © Sophie Prendergast

But why do we go to such lengths to uncover the mysteries of elasmobranch movement patterns? The answer is simple, to support development of effective conservation strategies within the Azores and the wider Atlantic as the region may have a disproportionate ecological and refuge importance for these threatened elasmobranchs. Such information is also critical to support sustainable eco-tourism in the region, one important driver of economic growth. In collaboration with the regional government data collected by the EcoDivePWN team will be used to help guide development of additional conservation measures to support the Sustainable Development Goals outlined by the Azores 2030 Initiative. Located near the center of the North Atlantic, conservation efforts in the Azores have the potential to create the world’s first high seas refuge for migratory marine organisms currently facing substantial pressure from human activities. The EcoDivePWN team is just one of many groups at the University of the Azores – Okeanos, working to preserve this unique oasis for marine life.

**References

[1] Das, D., and Afonso, P. 2017. Review of the Diversity, Ecology, and Conservation of Elasmobranchs in the Azores Region, Mid-North Atlantic. Frontiers in Marine Science, 4.

[2] Afonso, P., Porteiro, F.M., Fontes, J., Tempera, F., Morato, T., Cardigos, F. and Santos, R.S. 2013. New and rare coastal fishes in the Azores islands: occasional events or tropicalization process? Journal of Fisheries Biology, 83, pp. 272-294.

[3] Vandeperre, F., Aires-da-Silva, A., Santos, M., Ferreira, R., Bolten, A.B., Santos, R.S. and Afonso, P., 2014. Demography and ecology of blue shark (Prionace glauca) in the central North Atlantic. Fisheries Research, 153, pp.89-102.