Taking the Bait: Sharks, Prey, and Mysteries Beneath Fiordland’s Waves

During one of the mid-afternoon Baited Underwater Video (BUV) surveys in Dusky Sound, Fiordland, a small school shark circled curiously around the bait canister in front of the GoPro. Then, suddenly, it darted away. Out of the gloom came a massive shape, moving smoothly and deliberately — a male white pointer shark had arrived to investigate. Then quick as it had appeared, it swam back into the blue.

Across 204 BUV surveys conducted over 10 days, this rare encounter was one of many surprises — a reminder that even the most familiar waters of Fiordland can hold remarkable mysteries below the surface.

Getting Baited Underwater Video (BUV) equipment ready for deployment. Photo © Eva Ramey

What Is a BUV?

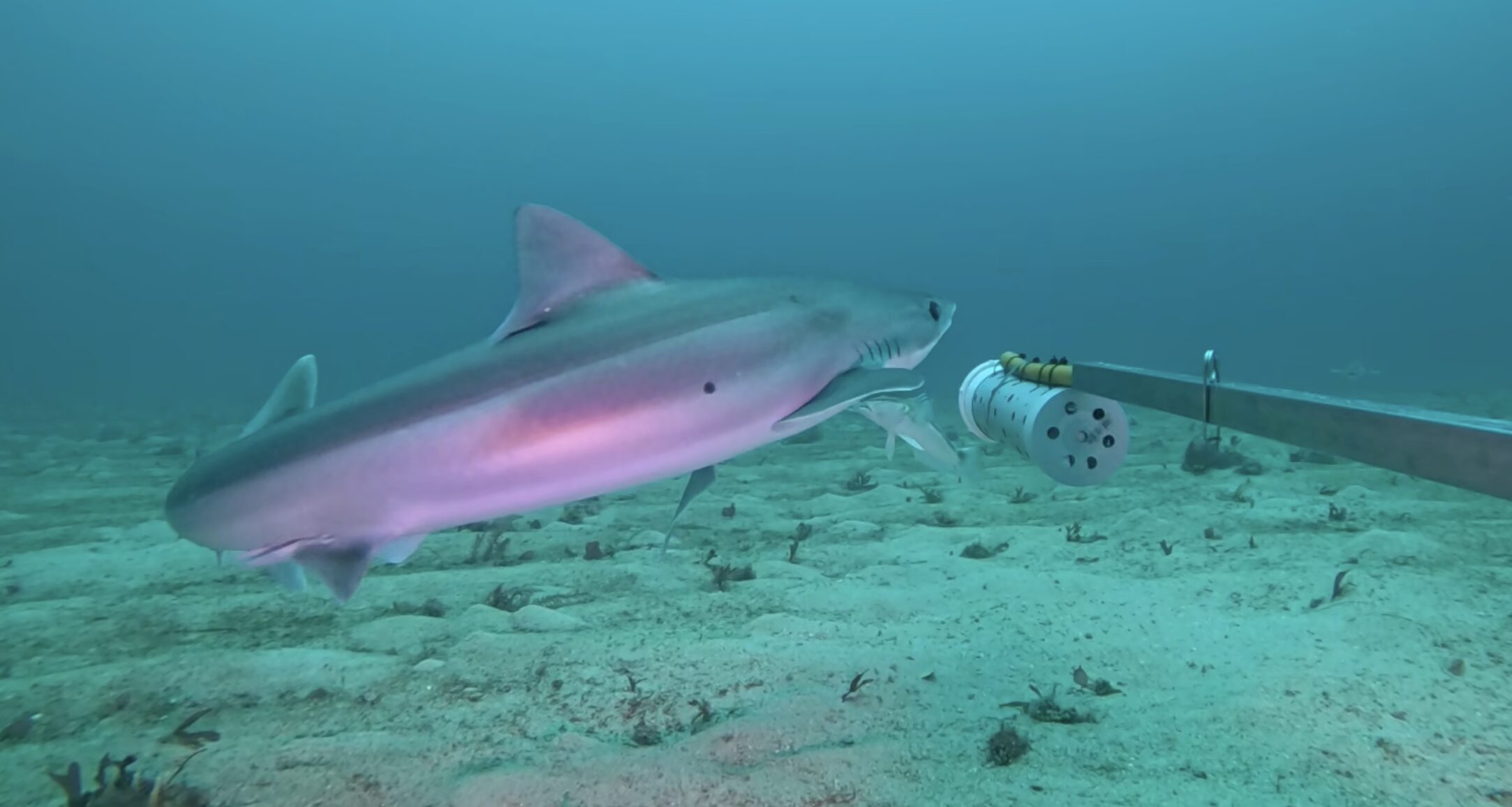

A Baited Underwater Video (BUV) system is a simple yet powerful research tool: two GoPro cameras and a bait canister mounted on a frame and lowered into the ocean. This setup provides a window into the hidden world beneath the waves, allowing researchers to observe fish communities in their natural habitat.

For my research, these BUV surveys will help offer insights into fish community structure and prey availability for coastal sharks, including school sharks (Galeorhinus galeus), spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias), and broadnose sevengill sharks (Notorynchus cepedianus). The BUVs also capture detailed imagery of the seafloor, revealing habitats that support Fiordland’s fish communities and provide insight into the habitats used by coastal sharks.

The deployment of these BUV survey was carried out in collaboration between the Department of Conservation and Sea Through Science as part of a broader effort to also assess fish diversity in Fiordland and evaluate the effectiveness of marine reserves.

Female broadnose sevengill cautiously eyeing the BUV. Photo © Adam Smith | Sea Through Science

Large male school shark/tope investigating the bait pole. Photo © Adam Smith | Sea Through Science

What Did We Find?

Across Dusky and Breaksea Sounds, the 204 BUVs that were deployed highlighted the region’s substantial biodiversity. Several sites showed high numbers of prey species and frequent appearances of broadnose sevengill and school sharks, suggesting the possibility of aggregation areas. These early results provide valuable insights into spatial patterns of prey availability for coastal sharks across Fiordland’s marine habitats.

Sunset over the fiords. Photo © Eva Ramey

What Comes Next?

As our acoustically tagged sharks continue to be tracked using an array of stationary receivers, the next step is to integrate movement data with habitat and prey information. By linking shark movements with habitat and prey data, we can begin to identify the specific areas these sharks rely on — and ensure those habitats receive the protection they need.