Sublethal injuries to Maldives manta rays

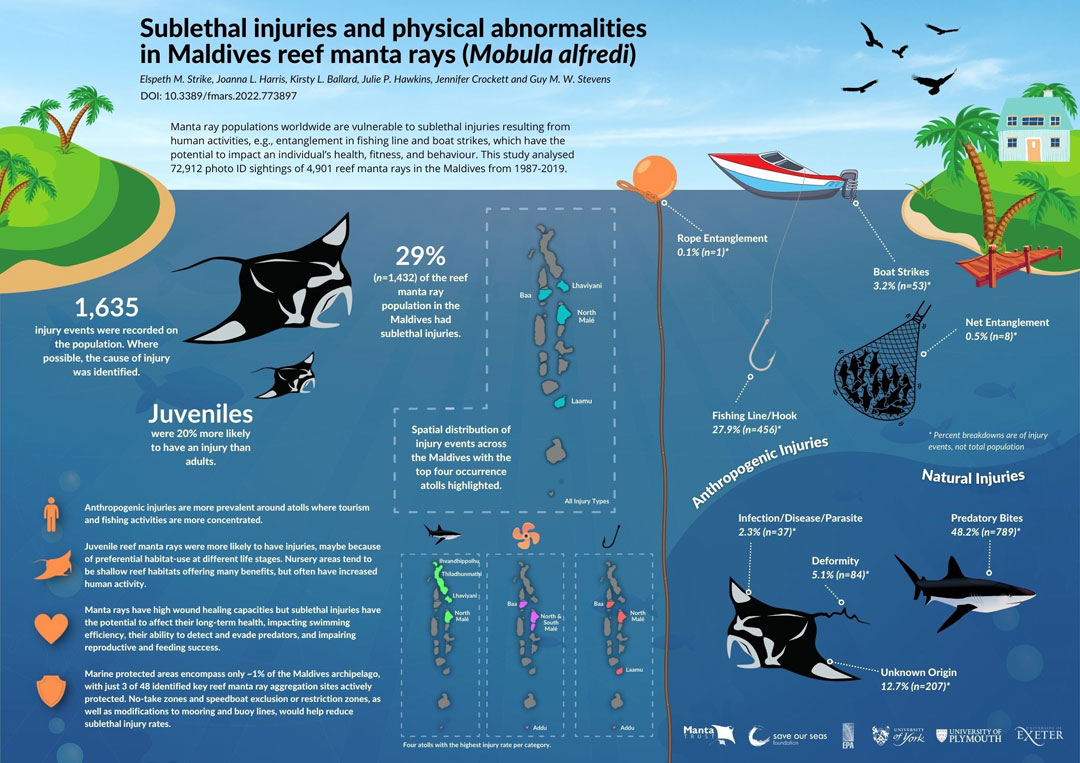

Manta rays all around the world are vulnerable to injuries caused by human activities, like being entangled in fishing lines or hit by boat propellers. While manta rays do have a speedy capacity for wound healing, the long-term effects of these injuries on their health and fitness are an important gap in our knowledge and conservation efforts.

When the Manta Trust’s Maldivian Manta Ray Project encounters manta rays during surveys, we record any injuries present. These include large, permanent wounds, scars, missing tissue, or disfigurements, which remain visible for the rest of the manta ray’s life. Recently, we published a summary of all the sublethal injuries and physical abnormalities recorded for manta rays in the Maldives, based on over 73,000 photo-identification (photo-ID) sightings collected over three decades.

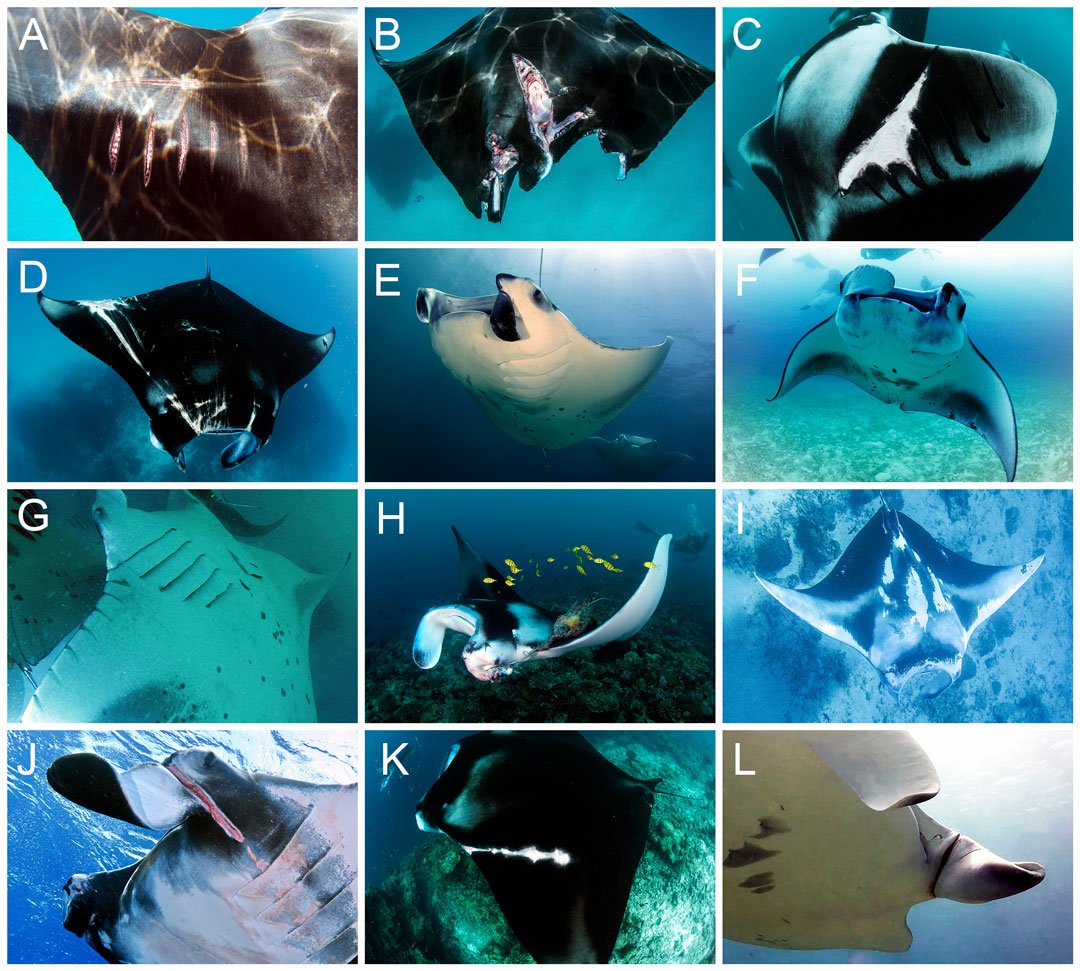

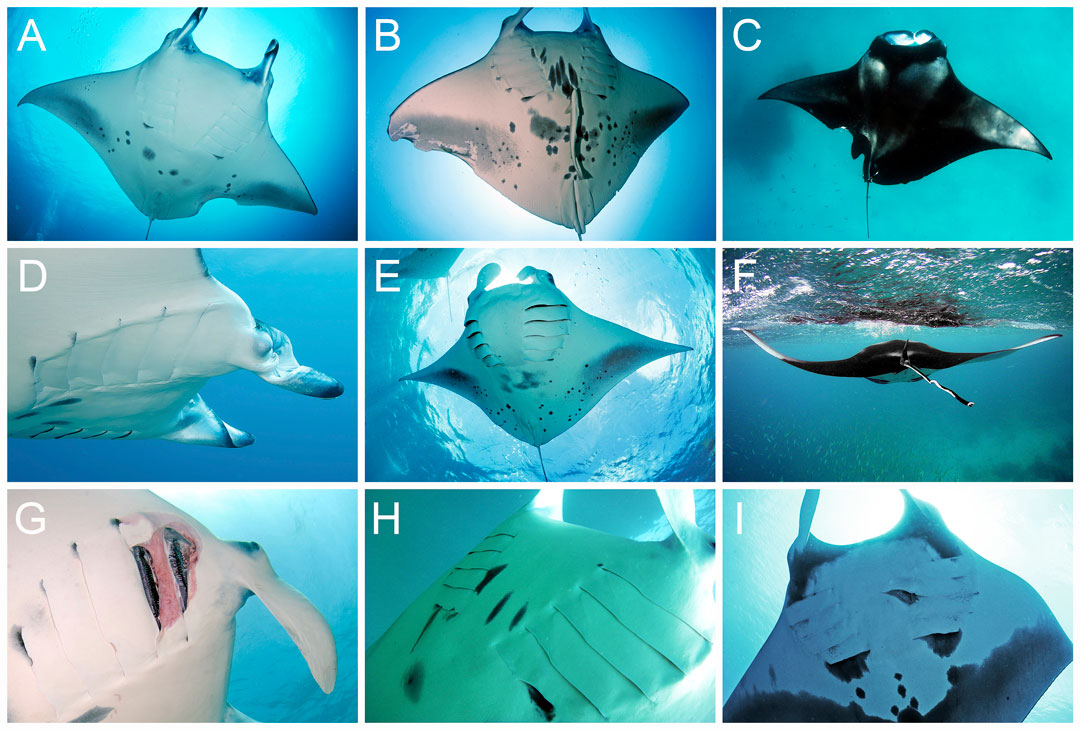

By examining photo-IDs of reef and oceanic manta rays, we identified seven different types of sublethal injury or physical abnormality (collectively called ‘injuries’) and categorised them based on their likely origin: either anthropogenic (human-related) or natural. The anthropogenic injury types we identified were boat strikes, entanglement in fishing line, net entanglement, and rope entanglement; while natural types were predatory bites, infections, diseases, or parasites, and birth deformities. Any injuries we couldn’t identify were recorded as “unknown”, and if multiple injuries to an individual were clearly from the same event (e.g., multiple fresh shark bites), we grouped them together for our analysis.

Examples of anthropogenic injury types for reef (Mobula alfredi) and oceanic (M. birostris) manta rays: (A—C) Boat strike; (D—F) Fishing line/ hook; (G—I) Net entanglement; (J—L) Rope entanglement. Images © Manta Trust.

Our study looked at the relationship between the type/frequency of injuries and sex and maturity status (either adult or juvenile) for both manta ray species, with additional spatial and temporal variables investigated for reef manta rays. This is the first time all the sublethal injuries and physical abnormalities of a manta ray population have been studied in this way.

Examples of natural injury types for reef (M. alfredi) and oceanic (M. birostris) manta rays: (A—C) Predatory bites; (D—F) Deformity; (G—I) Infection, disease, and parasitism. Images © Manta Trust.

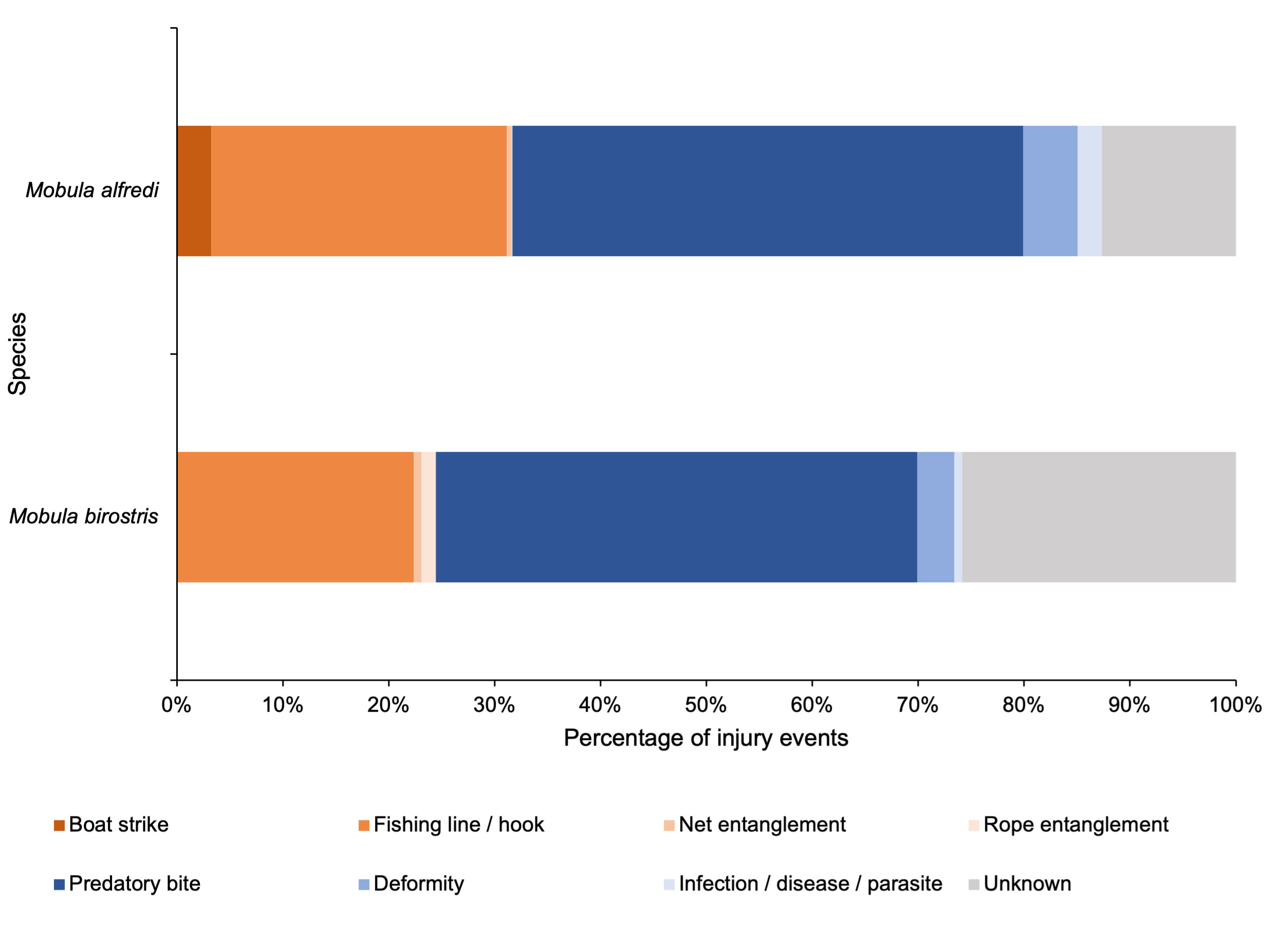

Predatory bites, usually from large sharks, like tiger (Galeocerdo cuvier) and bull (Carcharhinus leucas), were the most common injury type for both manta ray species, while the most frequent anthropogenic injury was entanglement in fishing line. Although manta rays in the Maldives are protected nationally and have never been targeted by a commercial fishery in the region, our study shows incidental bycatch (accidental capture or interaction with fishing gear) and boat traffic pose a significant threat to these animals, especially in busier atolls with more tourism and fishing activities like North Malé, South Malé, Baa, Addu, and Laamu Atolls.

A comparison of injuries recorded for reef (M. alfredi) and oceanic (M. birostris) manta rays by origin and type: anthropogenic (oranges), natural (blues), and unknown (grey).

Juvenile reef manta rays are especially vulnerable to anthropogenic injuries as they spend lots of time in shallow lagoons where boat traffic is heavy. Similarly, male reef manta rays were more likely to have anthropogenic injuries than females, as they too spend more time in shallower habitats for reasons like food availability or predator avoidance. Injuries to reef manta rays were most likely to be observed at cleaning stations as opposed to feeding or cruising sites, probably because manta rays visit cleaning stations for wound healing and parasite removal. However, for oceanic manta rays, neither sex nor maturity status appeared to affect the frequency of injuries, but we believe this analysis would benefit from a more comprehensive dataset.

Sublethal injuries and physical abnormalities in Maldives reef manta rays. Illustration © Manta Trust

As marine traffic, tourism, and fishing activities in the Maldives continue to increase, it’s likely that injuries to manta rays will become more frequent, which could affect the health and fitness of these populations. This study greatly improves our understanding of the relative impact of the different types of threats to manta rays in the Maldives. Conservation management actions to better protect these threatened animals throughout their range should include the establishment of no-take fishing zones and speedboat exclusion (or restriction) zones in areas of critical manta ray habitat, like feeding and cleaning aggregation sites, and juvenile nursery habitat.

This publication is a result of decades of data collection in the Maldives, including countless citizen scientist submissions from tour operators and divers. It’s also fantastic to see published literature stemming from the work of the master’s students we support.