South Florida Silkies in Summer

Another year went by and the silkies returned to South Florida. From late spring to early summer, they appeared one after another until local dive operators were seeing tens of silky sharks darting in and out of the chum slick avoiding the burly bulls and cartoonish sandbars. In mid-July, social media posts from shark divers made their arrival clear and highlighted their value to the tourism industry.

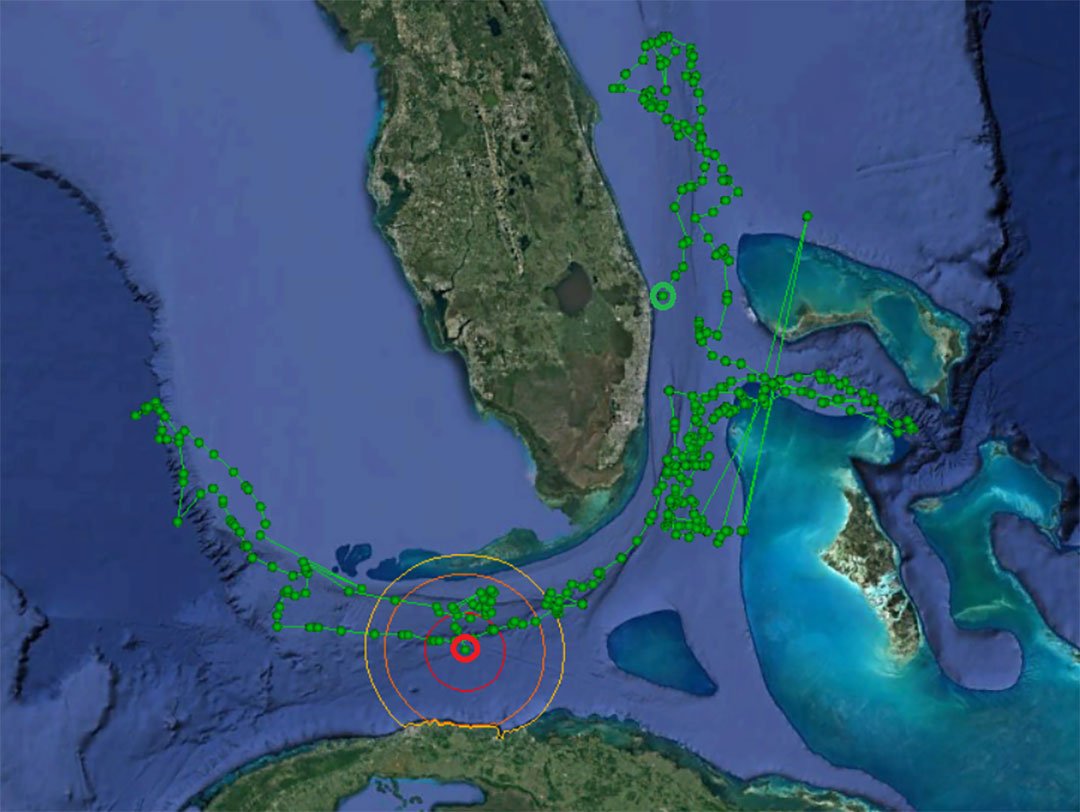

I’ve looked forward to fishing the deep ledge off Jupiter, Florida since Hannah Medd, founder of the American Shark Conservancy (ASC), deployed a satellite tag on a large male in the summer of 2020. Four months later, that tag connected with satellites just south of the Florida Keys. The most likely track suggested the shark moved north from Jupiter to Daytona Beach, then south and east into the central Bahamas, then along the continental shelf edge into the eastern Gulf of Mexico. The track highlighted the potential for large silky sharks to move long distances across international boundaries – no surprise for a shark species that has been documented moving more than 1,000 kilometres from the US east coast to Mexico’s Campeche Bank.

The most likely track of a male silky shark tagged off Jupiter, Florida in 2020. The green and red circles denote tagging and pop off locations.

Fishing along the south Florida coast is very different from fishing in the eastern Bahamas. I’m accustomed to fishing along a coastline dotted with casuarina trees and lined with mangroves. Other boats are few and far between, and we build a chum slick stretching kilometres while chumming for hours on end. When a shark chases the oily slick to our boat, we often hop in to confirm its ID, but rarely is a blue water shark anything but a silky in northern Exuma Sound. The coastline of South Florida is a different story. It is smothered in high-rise condos and beach tiki bars, and docks and marinas provide thousands of boat owners access to nearshore waters. Josh, a local captain and shark dive operator from Emerald Charters, volunteered to help us find the sharks and noted that he often counts over 100 boats on the horizon. The underwater scene is similarly foreign to me – bull, sandbar, Caribbean reef, blacktip, lemon, and dusky sharks are as likely as a silky to emerge from the blue. Boats dripping bonito attract a remarkable diversity and abundance of local predators like those that Ashley Wechsler, an undergraduate intern with ASC, lured up to our boat with persistent baiting. In-water experts like Josh, as well as Matt Lilly and Cassie Scott from Shark Addicts, another local shark dive operation, explained that depth predicts the dominant species. To find silkies, we would start deep and work shallow, hoping to pick them up in ones and twos without the dominant bulls chasing them away.

Researchers from FIU and the American Shark Conservancy begin to measure a silky shark alongside the boat. Photo © Cassandra Scott.

We chummed intensely for two days. The abundance tantalizingly visible on social media the week before our arrival was nowhere to be found; each silky was hard-earned. A combination of optimism, local knowledge, and fresh bait got us the two animals we eventually sampled and tagged – the first, a large male, and the second, an even larger female. We collected our usual suite of samples such as blood, muscle, faecal material, and a fin clip to investigate silky shark diet and build on our genetics database. The archival satellite tags bridled to each dorsal fin will pop off in four months, giving us another round of data to incorporate into our understanding of silky shark movements in the western Atlantic.

Next on the final (?) tagging tour is the Gulf of Mexico, where I hope to tag more adults far offshore along the continental shelf edge. The weather looks questionable, so we’ll do all we can and hope for the best. Fingers crossed that we can share the results of a successful trip shortly after.

As always, this work was only possible through the hard work of many generous individuals. You know who you are – thank you.