Silky smooth sampling in the Gulf of Mexico

Finally, the Gulf of Mexico was in sight. For months, we had searched for the goldilocks combination of weather, feasibility, and health & safety to allow a trip to Port Fourchon, Louisiana. We gambled on a two-day trip in late March when we hoped water offshore would be less chocolate milk and more Aquafina blue. In between fronts, we found our window.

The FV Whiskey Girl at dock in Port Fourchon, Louisiana, a busy industrial oil town. Photo © Cheston Peterson.

I set out with Cheston Peterson from the FSU Coastal and Marine Lab, John Carlson and Andrea Kroetz from the NOAA Panama City Laboratory, and Captain Brett Falterman from Fish Research Support to try our luck aboard the F/V Whiskey Girl, a 42’ Downeast as comfortable targeting tunas in the Gulf of Mexico as pulling lobster from the Gulf of Maine. We all felt the pressure of the upcoming trip as we tried to make up for lost field time during 2020 and kept a wary eye on dwindling project resources. We had 48 hours before temperatures were predicted to drop and wind would make working up sharks all but impossible. Factoring in the roundtrip travel to our sites offshore, we had 18 hours of fishing ahead of us.

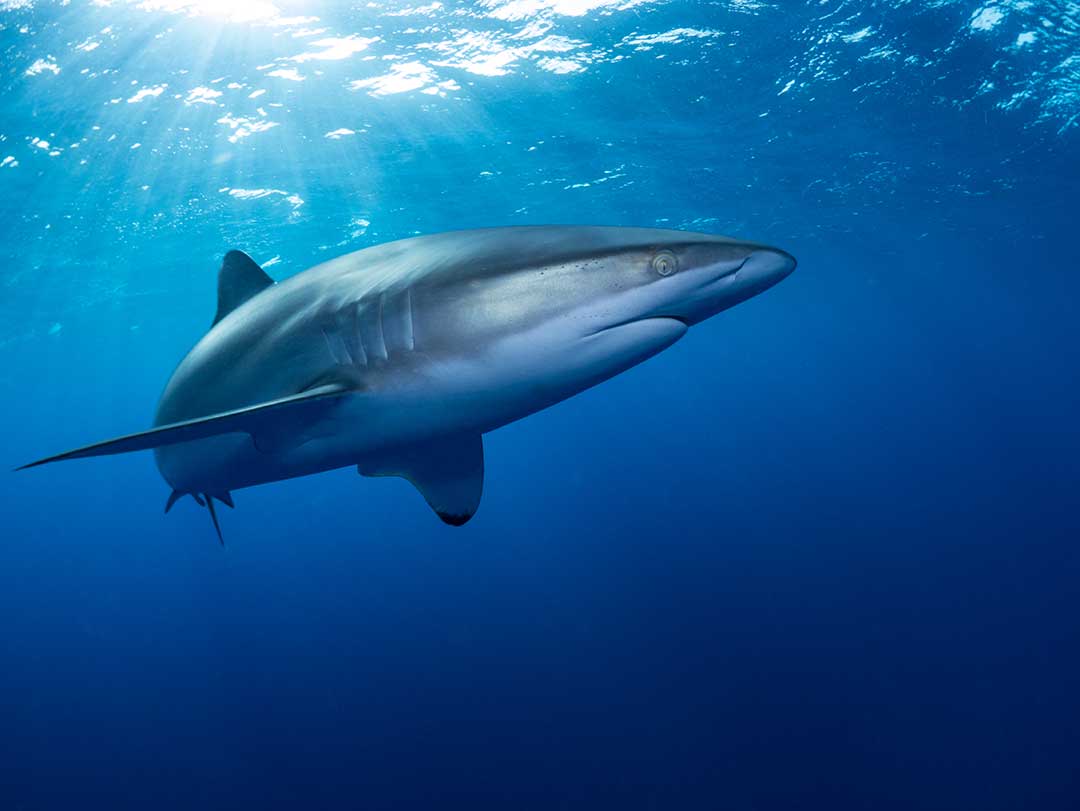

Silky shark populations are also on the decline. Photo by James Lea | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Although silky sharks are one of the most abundant sharks on the planet, their populations have declined globally, and have decreased more than 50% in the Gulf of Mexico since the 1950s. We suspected that we’d have a hard time finding them. From my experience searching for silky sharks in The Bahamas, I was mentally prepared to chum during every second at sea to get maybe one or two tagging opportunities. But the marine ecosystems of The Bahamas are nutrient-poor, while the Gulf of Mexico receives huge quantities of nutrients from freshwater outflows like the Mississippi River and other coastal drainages. The Gulf’s productive waters support large fisheries, and offshore features like oil rigs and seamounts draw pelagic and coastal-pelagic species to precise locations where prey is abundant.

An oil rig, one of many in the northern Gulf of Mexico, where we fished for silky sharks. Photo © Brendan Talwar.

The research team prepares to release a satellite-tagged silky shark back into the water. Photo © Andrea Kroetz.

We woke at dawn on the one and only full day of the trip. The lights of a large, operational oil rig shone through the Whiskey Girl’s windows and glistened off the water as the sky turned light pink and orange. Captain Brett dropped the first chunk of Atlantic mackerel into the water, and tens of silky sharks immediately swarmed the stern – unmistakable from their short, rounded first dorsal fin, and long, trailing edge of their second. We were ecstatic and jittery after months of working at the computer and shook off the rust during our first few workups. Before breakfast, we deployed four satellite tags sourced through NOAA’s partnership with the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas. For the next day and a half, we sampled silkies ranging from less than one meter long to a large 205 cm female, literally hooking silky sharks inches from the boat until we ran out of sampling gear. The muscle and blood samples we collected will give us insights into silky shark diets at locations ranging from deep, pelagic habitats to more shelf-associated reef habitats in just a few hundred feet of water. Faecal swabs will give us species-specific snapshots of prey items, which might include squids, bony fishes, and even sargassum-associated crustaceans. And, importantly, in a few short months, the satellite tags that we deployed will pop-off and transmit the depths, temperatures, and light levels from wherever our four tagged silky sharks swim off to, giving us a first look at their potential residency, migrations, and habitat use in the Gulf of Mexico.

It feels good to be one step closer to finishing the study, and our spirits are buoyed by a wonderful time at sea with good people, lots of sharks, and productive sampling.

A silky shark returns to the water with a satellite tag attached to its dorsal fin. Photo © Andrea Kroetz.