Sharks in the deep: how and why are they different?

Deep-water ecosystems are unlike any other habitat on our planet. Imagine (if you can!) living in a world 200 metres below the ocean’s surface. At this depth sunlight is very limited and the temperature is usually cold and unchanging. What little light exists is produced by other species through chemical reactions. But is it being produced by a friend, dinner or a hungry predator? It can be difficult to tell in the inky black depths.

Because there is no sunlight, plants don’t have enough energy for photosynthesis, the process by which they normally convert raw materials into food. So a vegan diet probably won’t cut it down here. All your food must either fall from the surface, like dead plants and animals, or you have to eat your fellow deep-water dwellers. This means that resources will be scarce and it may be a while, perhaps weeks, until your next meal. Most importantly, you have to remember that your eyes are of little value in the darkness. To survive, you must learn to rely on your other senses.

For sharks and rays living in the deep ocean, moving, eating and mating are no easy tasks. To cope with the lack of light and little food, sharks have developed a wide range of adaptations. For example, many sharks have a powerful sense of smell that enables them to detect their prey far in the distance. They can also detect subtle vibrations given off by other animals as they move through the water. To avoid starving to death, a shark living in this habitat probably has a very low metabolic rate and grows much more slowly than many other species do. It is also unlikely that it will have the resources to bear a large number of pups, so over the course of their lifetime, deep-water sharks and rays will probably produce far fewer offspring than many of their cousins living in shallow water. It also likely that deep-water sharks take much longer to reach a size at which they are able to mate and give birth. As you can see, the differences between deep-water and shallow-water sharks are like, well, night and day.

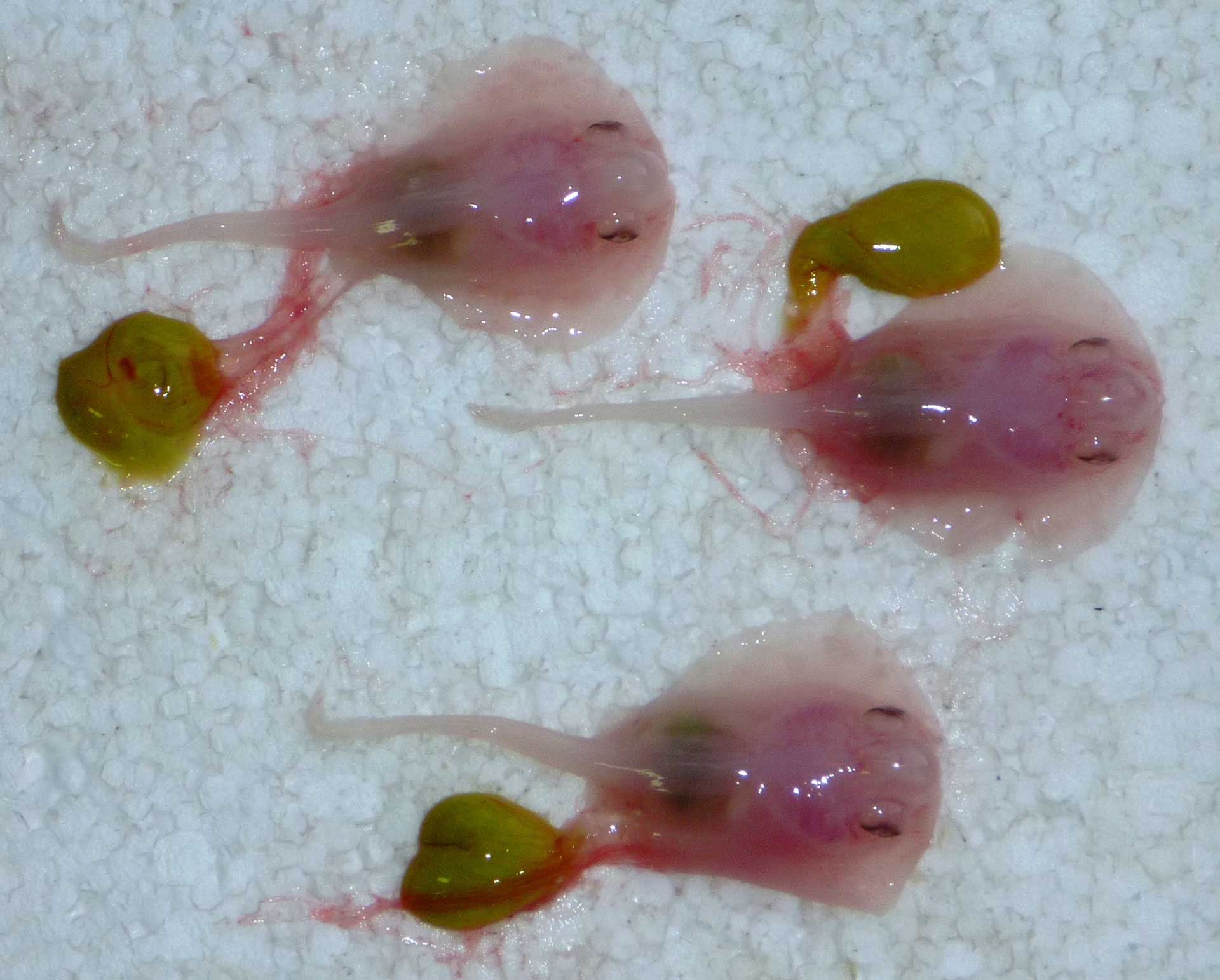

Photo © Cassandra Rigby

The stingaree embryos in this photo show just how small newborn deep-water species can be. The Coral Sea stingaree Urolophus piperatus is found at depths of between 171 and 370 metres on the continental shelf off northern Queensland. Not much is known about this species, but it is believed to give birth to only one or two pups a year. These pups are a meagre 12 centimetres long when they are born.

These differences mean that it is incredibly important for us to learn as much as we can about deep-water sharks because what we know about sharks at the surface may not apply to them. We lack basic information about deep-water sharks that is critical for their conservation and management. Generally speaking, we have no idea what they eat, how far they move or how they interact with one another. How can we protect something when we don’t know anything about it? Looking to the future, it’s important we dedicate more of our time and effort to studying these amazing creatures.