Shark skin sleuthing

Dermal denticles are tiny tooth-like scales that line the skin of nearly all elasmobranch species, providing a hard yet flexible armour that is gradually shed and regenerated. Their hydrodynamic design has provided inspiration for swimsuits worn by Olympic athletes, drag-eliminating coatings for vehicles, and even surfaces that impede bacterial growth in hospitals. But can they be used for shark conservation?

Mounting evidence documents the decimation of shark populations at the hands of overfishing, reef degradation and pollution, but to precisely what extent remains unknown. Survey data stretch back only about 50 years, after marine ecosystems had begun to decline, which highlights the growing need for a longer-term perspective on what is ‘natural’. In other words, how can we restore shark communities if we don’t know what constitutes a pristine population?

Collecting bulk samples of sediment while diving on a modern reef in Bocas del Toro, Panama. © Photo by Sean Mattson

Being cartilaginous, sharks don’t preserve as complete fossils, and their teeth are too rare to document past populations comprehensively. However, dermal denticles accumulate and preserve exquisitely in sediment on coral reefs and are much more abundant than teeth on a living shark. These fossilised denticles enable us to quantify changes in the relative abundance and diversity of sharks over time and to reconstruct what shark communities may have looked like prior to human activities. This information is critical for setting more accurate conservation goals.

First, though, we had to locate the denticles. Given their minute size (about the thickness of 3–5 strands of hair), it was like trying to find a needle in a haystack. We developed a novel methodology to extract denticles from reef sediment and to identify them both functionally and taxonomically to shark family using a reference collection of denticles. This technique was honed with sediment collected from modern reefs in Bocas del Toro, Panama. We then travelled back in time by sampling a rare, beautifully preserved, exposed reef site that is about 7,000 years old. Nearly half a ton of sediment was excavated in total, enough to fill several sandboxes.

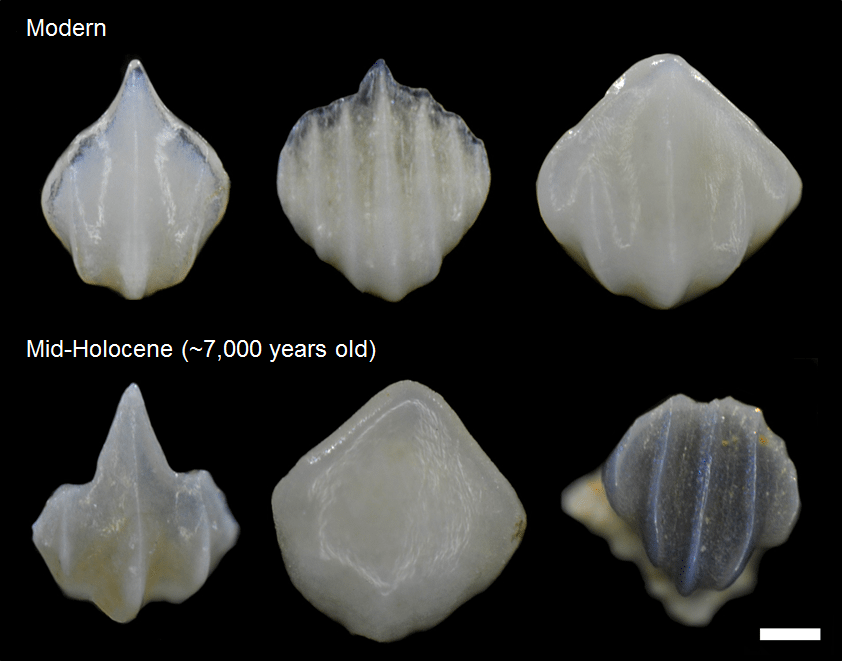

Light microscope images (80x magnification) of denticles extracted from modern and 7,000-year-old reef sediment in Bocas del Toro, Panama, showing the range of morphologies present and the high degree of preservation Scale bar = 100µm. © Photo by Erin Dillon

Not only did this sediment yield well-preserved denticles representing a range of classifiable morphologies, but it revealed a striking contrast between the denticles found on the historical reef and those extracted from modern reefs. This tells us that shark communities have shifted over the past 7,000 years in both number and composition, probably as a result of human-driven stressors.

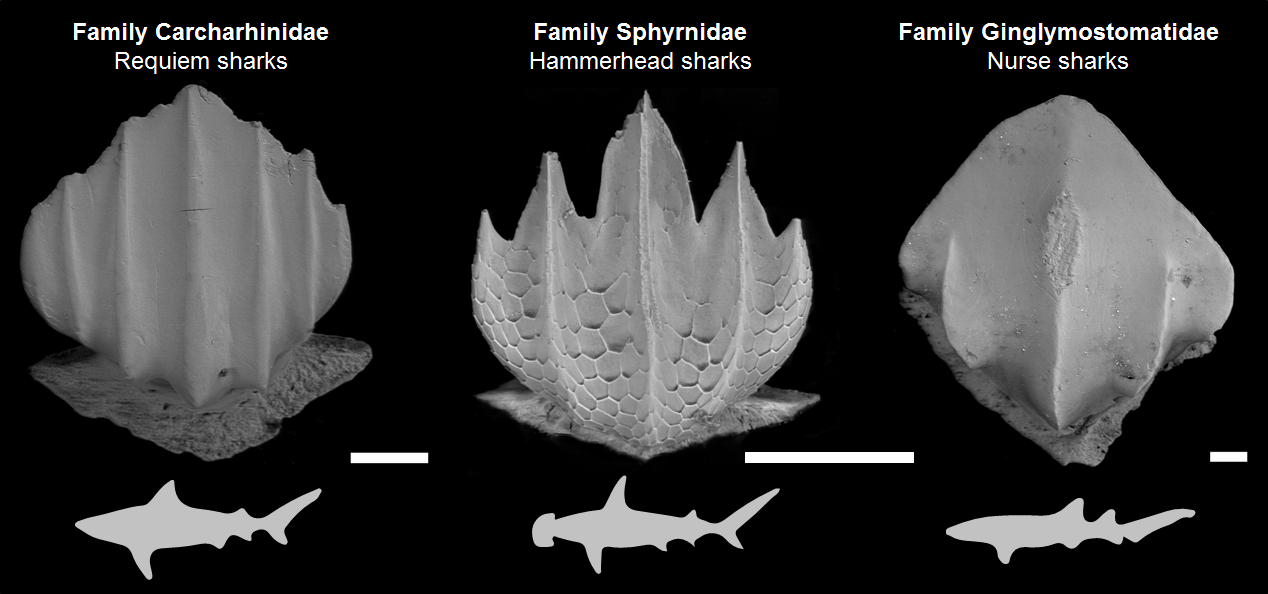

This has important implications in terms of how reefs function, given that different species of sharks play diverse roles within reef ecosystems. Denticle characteristics provide insight into the niche occupied by a shark. For example, fast predatory sharks are covered by thin, ridged denticles that resemble Ruffles chips, whereas demersal sharks possess thicker, smoother denticles. Not only did we find that there are fewer sharks in total on reefs today – indicated by a 37% decrease in the number of denticles extracted per amount sediment – but we observed a 31% reduction in the relative abundance of denticles of predatory sharks (requiem and hammerhead) and an 8% increase in the relative abundance of denticles of demersal sharks (nurse) on modern reefs in Bocas del Toro as compared to their historical counterpart.

The few visual surveys that have been conducted in this region report an absence of sharks, yet fishermen continue to catch them around the islands. However, we’ve discovered that these otherwise undocumented populations leave their mark in the sediment, and even denticles from cryptic, nocturnal and rare species that wouldn’t usually be spotted by surveyors can be identified. Thus, by turning to our palaeo-ecological toolbox, we can apply information from the past to manage shark populations and coral reef ecosystems in the present to better protect them in the future.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of shark dermal denticles from the three main shark families represented in our sediment samples A blacknose shark Carcharhinus acronotus denticle is shown for family Carcharhinidae, a scalloped hammerhead Sphyrna lewini denticle for family Sphyrnidae, and a nurse shark Ginglymostoma cirratum denticle for family Ginglymostomatidae All the denticles were isolated from pieces of skin excised from preserved museum specimens Scale bar = 100µm. © Photo by Jorge Ceballos and Erin Dillon