Searching for mobulas on land

Starting a project is always difficult. Many questions arise. How do you do it? Which are the steps to follow? What data you need? Who can help? Where do you get the money from? Luckily for me, I had a great guidance from the MC Azorean team. Likewise, I would also like to provide some guidance, and hopefully some inspiration, for those curious human beings around the world that want to unveil their natural environment.

There are different ways of studying nature, but here I will focus on the study of those cryptic, elusive species, that at first seem impossible to get to know better. In my case, these are the mobulas. Different species of the family Mobulidae, commonly known as mantas or devil rays, roam the Canary Islands waters. They can be seen all year round, but if you have had an encounter with them in the archipelago, you can feel fortunate. Although big groups of mobulas have been recorded and there seems to be a season when sightings are more frequent, spotting a mobula in the Canary Islands is a matter of chance. I myself, studying their presence for over two years, have been only lucky twice. So, how can a scientist study a species without seeing it?

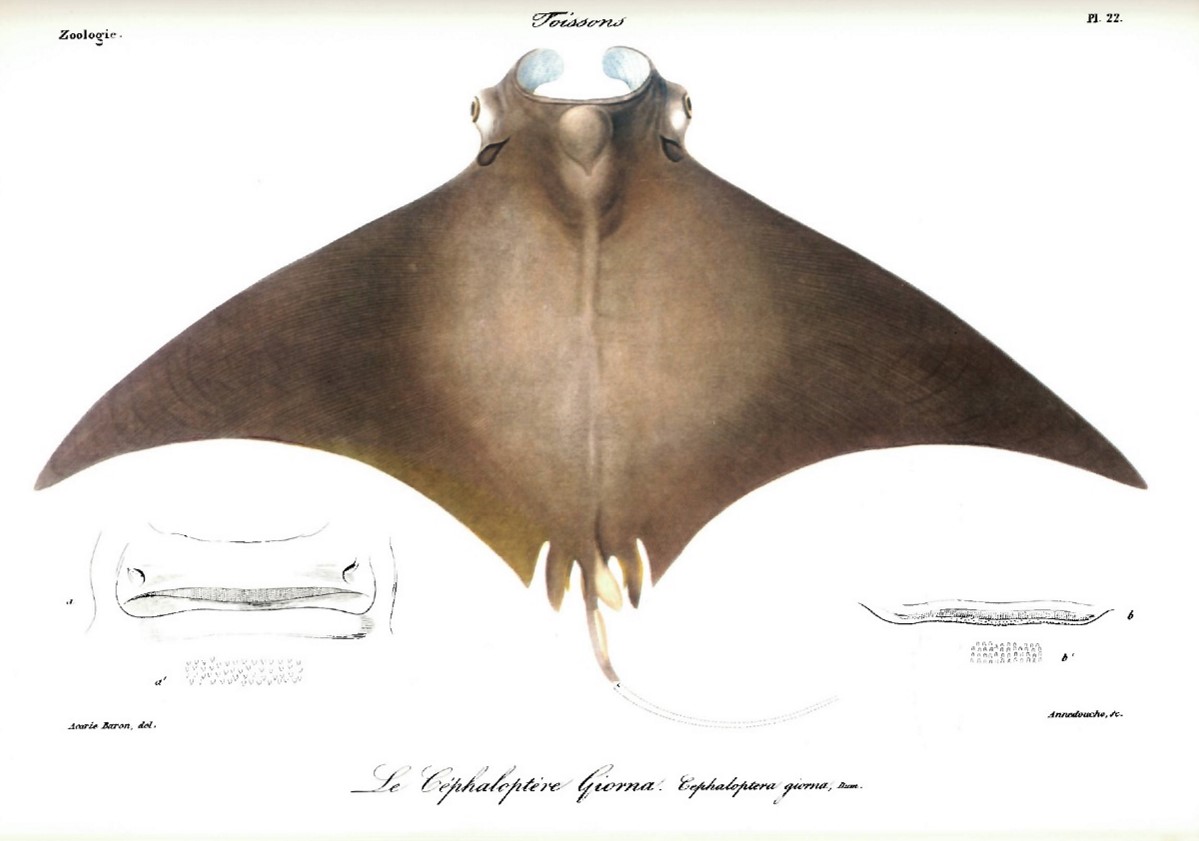

Drawing of Cephaloptera giorna (currently Mobula mobular). Source: Valencienne (1842)

For the Manta Catalog project, our first step was to gather all the information possible on the Mobulidae family. We noticed there was a huge research gap on this group in the Canary Islands and baseline information was lacking. So, how are we doing it? Perhaps, something that marine biology students don’t hear as much about, is that marine biology work is not always about being in the water. You will need to spend time in the computer, writing and analysing data. But if you really want to understand your species and contribute to its protection, this needs to be done too. And believe me, it’s worth it.

Since our inception, we have been connected to the natural environment for our basic needs. However, it’s not merely about sustenance; people have sought solace in nature, harnessed its resources for leisure or economic gain, and found inspiration within its beauty. Nature sticks into our memories and traditions. While some communities are more intimately tied to the natural world and its species, even when big cities are turning their backs on nature, you will still find offices decorated with wildlife photographs to keep the mood up, and suited businessmen and women running off to the countryside or beach on their holidays. Because we need nature. And you can find information in that human-nature connection.

To start with, you can investigate the language. In Spanish, and more precisely, in the Canary Island region, mobulas are called “maromas”. On the Basic Dictionary of Canarisms “maroma” is defined as: somersault, flip or pirouette of an acrobat or an acrobat’s imitator. Were mobulas named “maromas” because they were seen jumping out of the water in the archipelago? This could provide interesting information on the species behaviour.

Even though it sounds weird, you can also look for your marine species on land. In the Canary Islands, there is a ravine called “Barranco de la maroma”. Are mobulas seen frequently in this area? This could give you some hints on species distribution.

You can also delve into the past of your species, gaining valuable insights into the present. I took quite some time jumping from library to library, searching into scientific papers, books, field guides, photography collections… Will you be able to find the first time your species was cited for your area? Or find the first picture ever taken in the region? Local museums can also be a good place where to look.

Mobula birostris captured on the 22nd of april 1931 at La Luz harbour (Las Palmas). Up until now, this is the oldest mobula picture found for the Canary Islands. Source: Bellon & Bardán (1931).

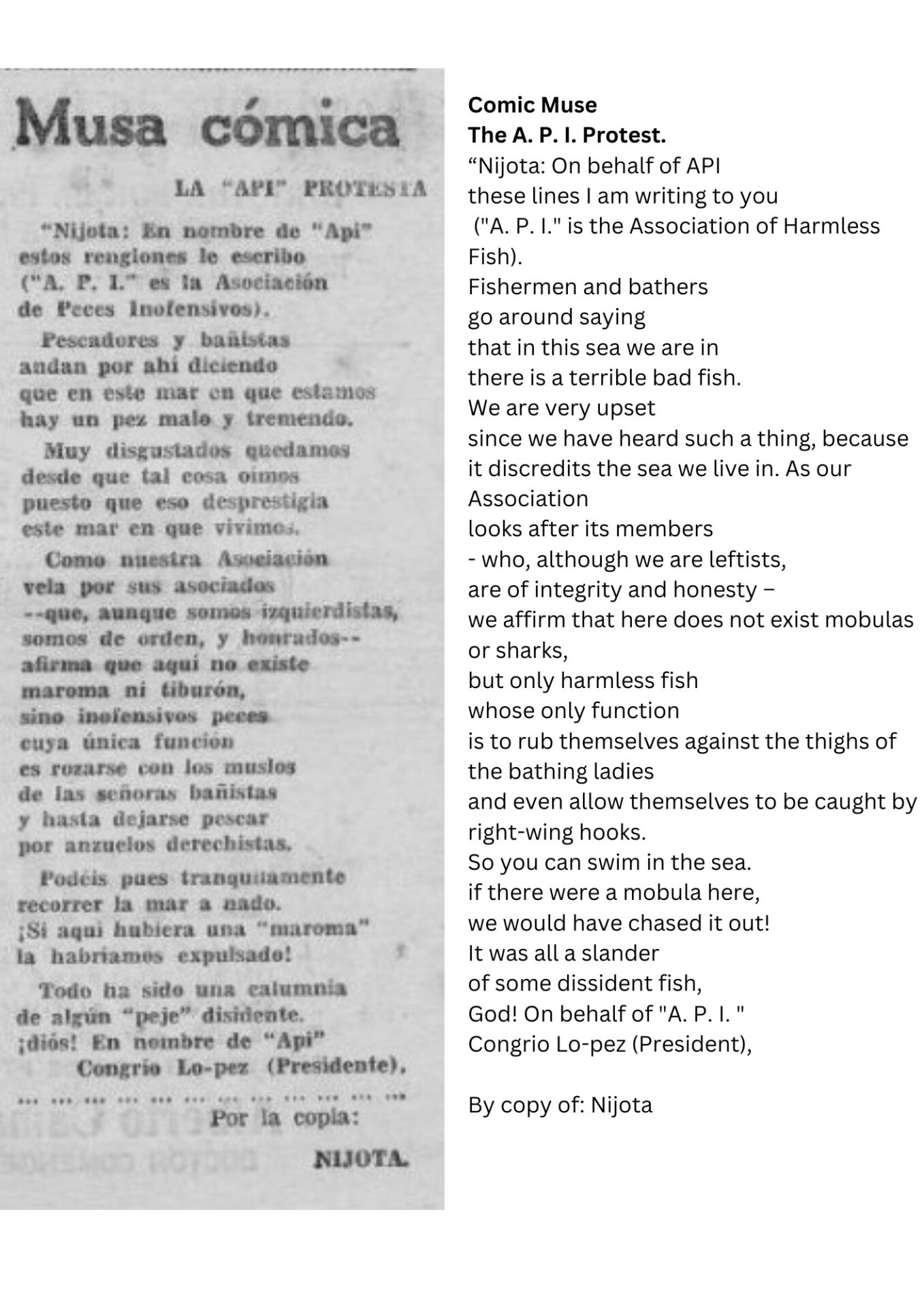

If you are lucky enough, you may have digitalized press on your region. For me, I have been able to track back mobula sightings up to 1888. Similar to other places in the world, people used to fear mobulas. Whenever an individual was seen near the coast, chaos spread out and parties of men were dispached to kill the sea monster. This apprehension towards these creatures even found its way into poetry and literature.

Poem titled “The A. P. I. Protest” printed in Musa Cómica (11th August 1933)

Exploring local businesses can be quite revealing. We’ve come across dive centers, shops, and restaurants that incorporate names like “Manta,” “Mobula,” or “Maroma.” It’s clear that these animals awaken significant interest among people.

And why not chat with the people? Local Ecological Knowledge can be defined as knowledge that is held by a specific group of people about their local ecosystems and has been derived from human–environment interactions. Fishers, divers, underwater photographers, and local residents can offer valuable insights into this subject. Every story matters, including those who claim to have never encountered a Mobula. Perhaps you’ll find yourself in the courtyard of an experienced fisher or underwater photographer, listening to their captivating tales and underwater adventures, for a bit more of time than you had planned. From it, you will be able to gather key information on species distribution, ecology and even potential impacts.

Lastly, and being the key to the success of this project, there is community science. Community science is the active contribution of community members in the collection of scientific data. We’ve managed to collect over 200 mobula sightings from the 8 volcanic islands that conform the archipelago. While I would have cherished the opportunity to witness these sightings personally, I would have never been able to collect that amount of data otherwise. Moreover, it is fulfilling to witness the shared excitement reaction of the collaborators in their videos and their eagerness to learn more about the results we’re obtaining. This is a collective effort, united by the people’s innate curiosity, and our will to protect what we admire.

Curators from the Museum of Nature and Archaeology of Tenerife next to a replica of a mobula that washed up on the coast of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Photo © Alicia Rodríguez Juncá

Altogether, it seems that mobulas are much more present around us than it previously seemed. With all these pieces you can start building your puzzle. So, after long talks with experienced seamen and women, diving into the history of your place and looking through other peoples’ eyes, I am sure you will get to know better your species, and through the way you will have gained much more.

Good luck with your research.