The saw-less sawfish?

The first time I saw a sawfish, I was mesmerised. The question that sprang instantly to mind – and also the one that I get asked the most – is, what is the saw used for? To say that I found this question fascinating is an understatement, as I spent four years of my life trying to answer it. My PhD project, which I finished in 2011, focused on the feeding behaviour and sensory biology of sawfishes. And I can tell you already, the deeper I got into the topic, the more fascinating it became.

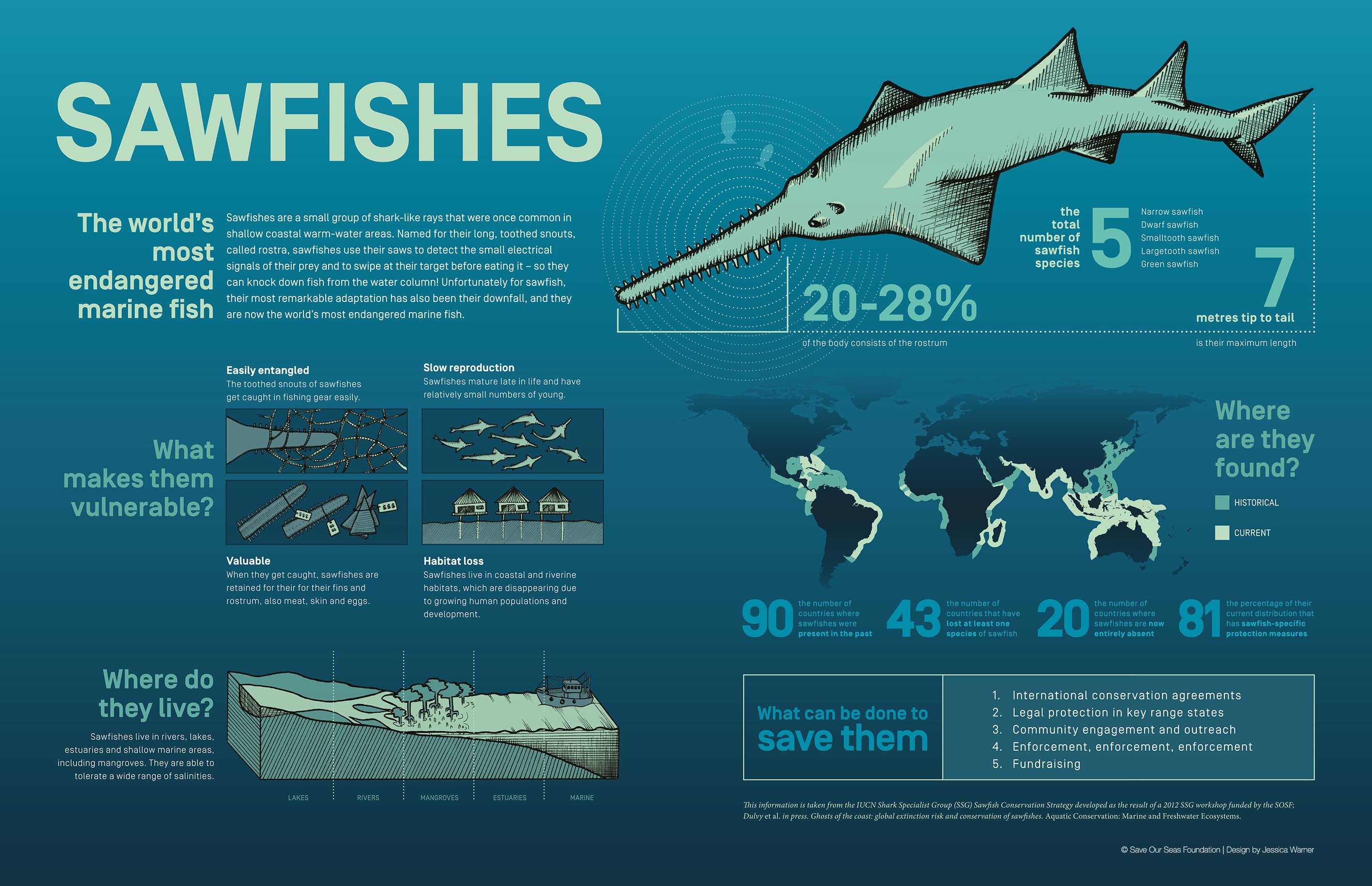

The saw is an elongation of the rostral cartilage. The elongated rostrum, which also bears lateral teeth, evolved at least three times independently in elasmobranchs: twice in rays and once in sharks – in the family Sclerorhynchidae (extinct sawfish), the family Pristiophoridae (sawsharks) and the family Pristidae (living sawfish). For my research I compared sawfishes with their close relatives the shovelnose rays of the family Rhinobatidae. As both taxa are likely to have evolved from a common ancestor that was similar to shovelnose rays, the comparison enabled me to provide a hypothesis about the evolutionary benefit of the saw in living sawfishes.

© Save Our Seas Foundation

My research found that the freshwater sawfish Pristis pristis uses its saw both to sense prey (via electroreception and touching) and to manipulate it. Interestingly, juvenile freshwater sawfishes slash at an electric dipole, which resembles visually hidden prey, only when it is suspended in the water. Shovelnose rays hardly react to these fields. When a sawfish encounters an electric dipole field on the bottom, just like a shovelnose ray it tries to gobble up the field source with its mouth. These results clearly indicate that the evolution of the saw enabled sawfishes to expand their hunting strategy to include fast, free-swimming prey.

The saw, however, is also what gets sawfishes into trouble. Saws easily get entangled in fishing gear and the sawfishes wrap themselves up even more in nets when they try to escape from the invisible danger, sometimes becoming dangerous to handle. Saws are also sought-after trophies. Even though all species of sawfish are listed on CITES and the four species in Australia are protected locally under federal and state legislation, saws can still sometimes be found for sale at local markets or on e-bay.

I had always thought that fishermen were taking whole sawfishes and selling the fins separately from the saws. After all, sawfish fins are among the most valuable in the international shark-fin trade and can fetch a few thousand dollars each. But there is a different, even more disturbing practice. Fishermen, both commercial and recreational, are cutting off a captured sawfish’s saw before releasing the animal alive. Although I had heard rumours about this practice, it was only in November 2015, when we finally ran the first research expedition with Sharks And Rays Australia to the Norman River, that I started to realise just how much of an issue it could be.

Situated in the south-eastern corner of the Gulf of Carpentaria, the Norman River is a Mecca for commercial and recreational fishermen who are after barramundi. It is fairly accessible, being one of the few destinations in the Cape York region that can be reached by a paved road. Moreover, public concrete ramps enable boats to be launched easily at Normanton, which lies inland on the river, and at the coastal fishing port of Karumba.

During the closed season for barramundi fishing, the boats parked in the Karumba gardens overshadow the houses. Photo © Barbara Wueringer | Sharks And Rays Australia.

Setting, checking and retrieving gill nets in this river was an adventure. We were manoeuvring in waters with an average visibility of 10 centimetres (four inches). Hidden under the surface were landscapes of boulders, sunken logs and sand bars that were only visible with the aid of modern technology. The presence of large saltwater crocodiles took the required alertness and protocols to the next level. We had prepared for encounters with all kinds of creatures, from our study species to sand flies, mosquitoes, stingrays and stingers. What made the sampling even more difficult was that the river was full of jellyfish. Our net setting required fine-tuning.

The entrance to a hide out of a saltwater crocodile Crocodylus porosus. The belly slide is around 50 cm wide, indicating a large animal. Photo © Barbara Wueringer | Sharks And Rays Australia

A group of pelicans is called a pod! Photo © David Nash | Sharks And Rays Australia.

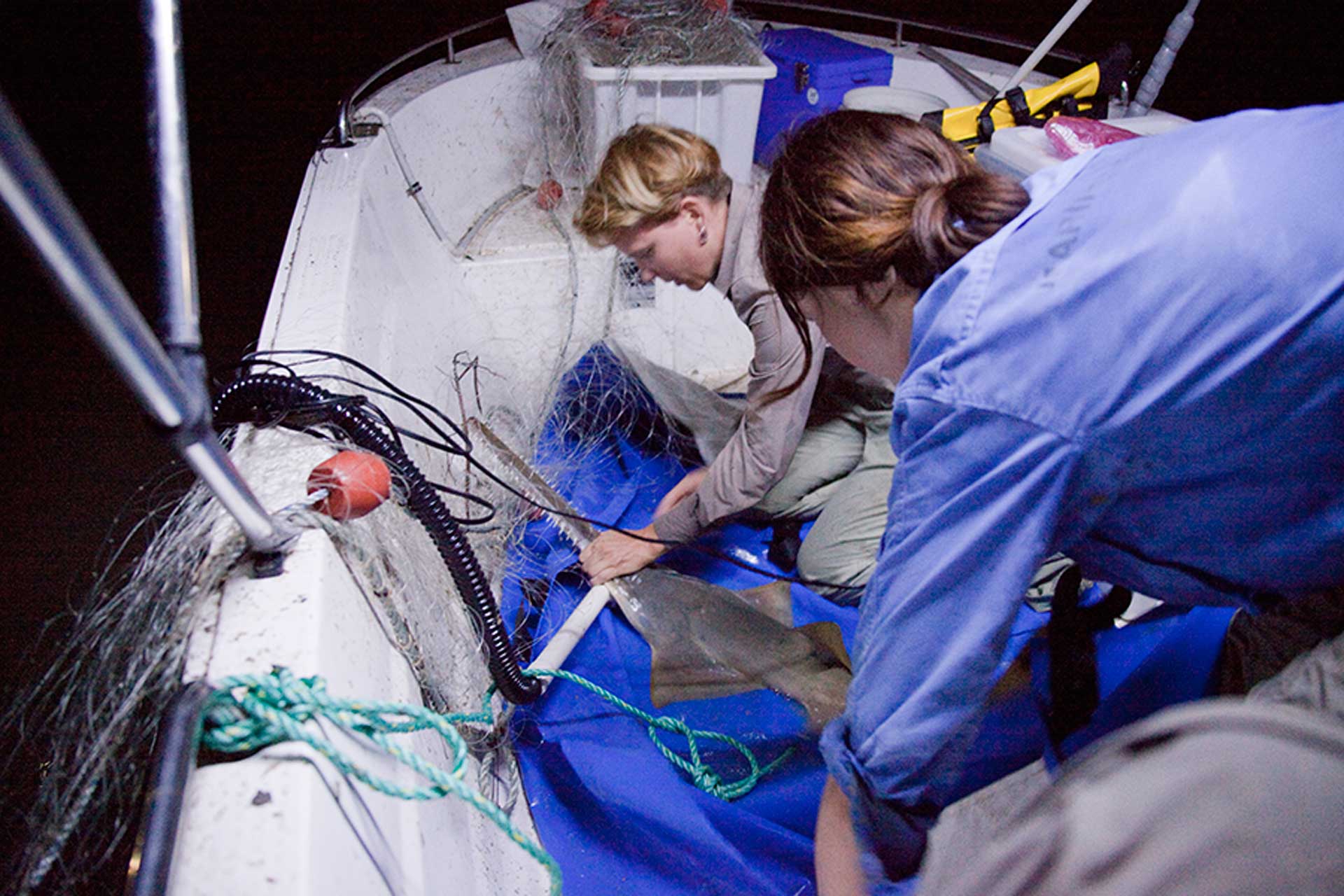

After four days of sampling we managed to capture, tag and release one juvenile bull shark and one sawfish. I don’t think that this low sample number reflects the sawfish population of the Norman River, but it will take many more field trips to find out. As a result of our outreach efforts while we were at the Normanton Tourist Park, we received reports of two accidental sawfish captures that took place just days before we arrived. When the sawfishes were captured by recreational fishermen, the saws of both were already missing. The fishes were released alive, but their chances of survival are slim.

Teagan Marzullo and Barbara Wueringer tag the first juvenile freshwater sawfish, Pristis pristis, captured for this study. Photo © David Nash | Sharks And Rays Australia.

Together with the Save Our Seas Foundation Media Unit, the material submitted was turned into an educational video so that this sad occurrence could be turned into an opportunity for public education. Please share it widely.

Facts

- In countries where sawfishes are protected, the removal of a sawfish’s saw is illegal.

- As sawfishes are listed by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), any international trade in sawfish body parts or live animals is regulated.

- In Australia sawfish are protected under the EPBC Act.

- When the saw of a live sawfish is removed, the brain cavity is opened, resulting in the sawfish’s slow, lingering death.

- A sawfish uses its saw to find and manipulate its prey. It also uses it to defend itself.

Further reading

Morgan DL, Wueringer BE, Allen MG, Ebner BC, Whitty JM et al. 2016. What is the fate of amputee sawfish? Fisheries 41(2): 71–73.

Seitz JC, Poulakis GR. 2006. Anthropogenic effects on the smalltooth sawfish (Pristis pectinata) in the United States. Marine Pollution Bulletin 52: 1533–1540.

Wueringer BE, Squire LJ, Kajiura SM, Tibbetts IR, Hart NS et al. 2012. Electric field detection in sawfishes and shovelnose rays. PLOS ONE 7: e41605.

Wueringer BE, Squire LJ, Kajiura SM, Hart NS, Collin SP. 2012. The function of the sawfish’s saw. Current Biology 22: R150–R151.

SARA's field team posing in front of a croc statue in Normanton, Queensland. © David Nash | Sharks And Rays Australia.