Sharks and Rays of Benin: Insights into Their Fisheries and Conservation Status

In the late 1990s, socio-bioeconomic studies identified approximately ten shark species landed in Benin through artisanal and industrial fishing activities. These species accounted for less than 8% of the total recorded catches, as documented by the Statistics Division of the Fisheries Management Authority of Benin. However, species misidentification due to the resemblance among many species, the lack of training of data collectors and a focus on artisanal fisheries at the only well-equipped harbour with less regard for other landing sites, a comprehensive understanding of elasmobranch fisheries in Benin remains elusive.

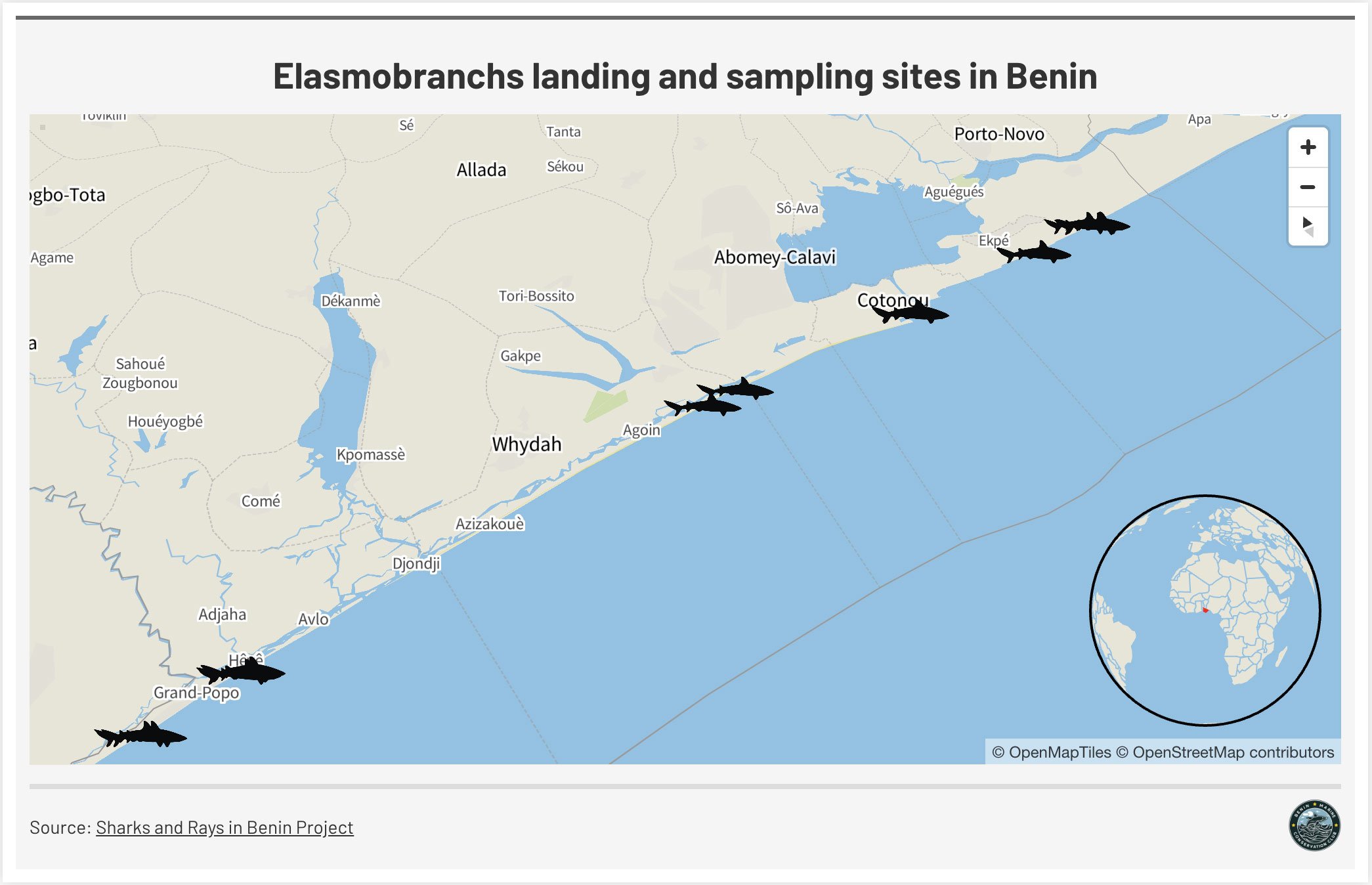

On average, around 250 elasmobranch individuals (sharks and rays combined) are landed weekly along Benin’s coastline. A detailed survey conducted over ten months included market observations, landing site assessments, informal discussions, and structured interviews using questionnaires. This study revealed that 29 elasmobranch species are fished in Benin’s coastal and marine waters, either seasonally or throughout the year. The survey covered the entirety of Benin’s 125-kilometer (77.6714miles) coastline.

The identified elasmobranch species fall into two main groups: sharks and rays. No chimera species have been recorded so far. Sharks are represented by four orders, nine families, and fifteen species, while rays consist of fourteen species distributed across four orders and eight families. Notably, most specimens landed—both sharks and rays—are mature individuals. The classification system is based on their shared physical traits and evolutionary relationships (this calls the use of genetic -DNA- tools).

The conservation status of these species is based on global assessments rather than regional evaluations. The findings include:

Data Deficient: 2 species

Least Concern: 2 species

Near Threatened: 7 species

Vulnerable: 6 species

Endangered: 4 species

Critically Endangered: 8 species

Hypanus rudis individuals landed and ready to be sliced before smoking. Photo © Houangninan Midinoudewa | BMCC

Gymnura micrura. Photo © Houangninan Midinoudewa | BMCC

Scyliorhinus cervigoni. Photo © Houangninan Midinoudewa | BMCC

Pteroplatytrygon violacea, Photo © Houangninan Midinoudewa | BMCC

The most frequently landed elasmobranchs include: Fontytrigon species (Pearl whipray and Daisy whipray), Glaucostegus cemiculus (blackchin guitarfish), Hypanus rudis (smalltooth stingray), Carcharhinus falciformis (silky shark), Prionace glauca (Blue shark), Carcharhinus leucas (bull shark), Dasyatis marmorata (marbled stingray), Raja parva (African brown skate), Rhinobatos rhinobatos (common guitarfish), Rhinobatos irvinei (spineback guitarfish), Mustelus mustelus (common smoothhound), Zanobatus maculatus (maculate panray), Zanobatus schoenleinii (striped panray), Squalus Blainville (longnose spurdog), Squatina oculata (smoothback angelshark), among others.

In addition to species identification, biometric data including physical attributes such as length, weight, maturity stages, presence or not of pre-expelled juvenile and other morphological features of the elasmobranchs data were collected. 562 DNA samples were preserved for future genetic analysis. Interviews were conducted with 57 fishers, including 12 female fishmongers. The fisher group comprised retired individuals, experienced active fishers (over 20 years in the sector), and younger active fishers (less than 10 years of experience). Only one retired fisher reported catching a sawfish (Pristis sp.) during his career in the late 1970s. These data are crucial for understanding species-specific growth patterns, reproductive status, and population health.

These findings are significant for:

They provide baseline data on the diversity and conservation status of elasmobranchs in Benin.

They highlight the prevalence of mature individuals in catches, which has implications for population sustainability.

The global conservation statuses show that many species are threatened (e.g., Critically Endangered or Vulnerable), emphasizing the need for targeted conservation measures. There is a need of regional or local statuses assessment.

The next steps include using the collected biometric data and DNA samples for further genetic analysis to confirm species identification and assess genetic diversity. These findings can inform regional conservation strategies, sustainable fisheries management practices, and international efforts to protect vulnerable elasmobranch populations.