Reeling in data: working with competitive recreational anglers to answer questions about the common eagle ray

It is really difficult for scientists to collect robust scientific information on our elusive species, such as sharks and rays. These remarkable species, often shrouded in myth and misunderstanding, are among the rarer and more difficult to study in the natural world. Environmental pressures, including overfishing, habitat degradation, and climate change, further threaten these species, heightening the urgency for accurate scientific insights. Yet, the very factors that make these creatures vulnerable also make them difficult to study, creating a race against time and a need for researchers and scientists to think outside the box of ways to effectively and sustainably study and manage these creatures. Further, unlike the more abundant teleost species, sharks and rays don’t often congregate in easily accessible populations, making any observations or robust scientific surveys a logistical challenge. Days and days of sampling may yield very few samples and as much fun as it would be, it would be hugely expensive for scientists and researchers alone to monitor the status of these fishes.

A newfound hope has been through competitive angling where scientists and researchers can collect critical information for our incredible coastal fisheries species including the common eagle ray!

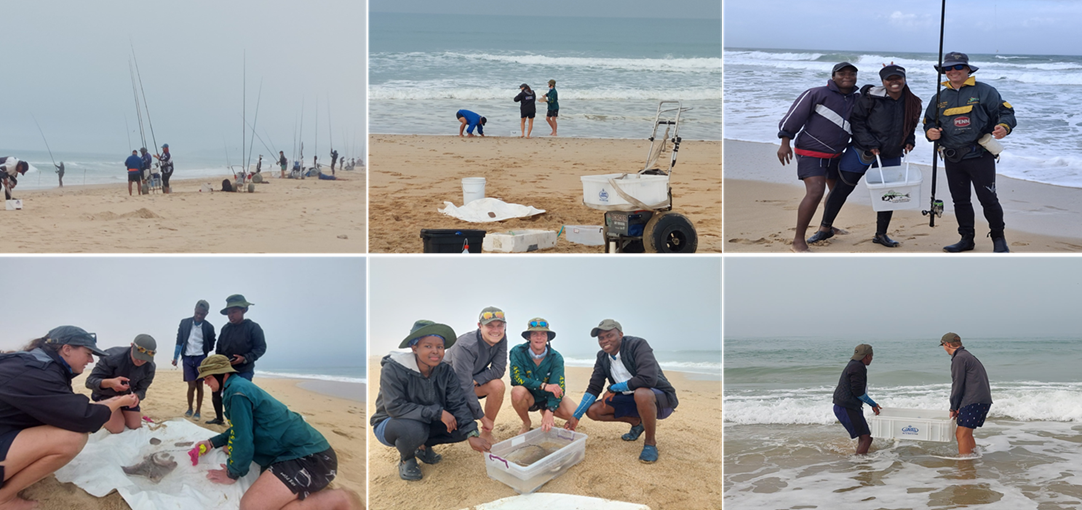

Researchers from the Southern African Fisheries Ecology Research Lab (SAFER Lab) at Rhodes University have been engaging with a group of competitive recreational anglers (Image 1), through the Rock and Surf Super Pro League (RASSPL) since 2013.

. Top left: RASSPL recreational anglers ‘at work’; top centre, scientists from Rhodes engaging with an angler; top-right, scientists and students using a bucket with fresh sea water to minimise air-exposure of fish; bottom left and centre, scientists tagging and collecting biological data from a common eagle ray from the ray and bottom right SAFER Lab students releasing the common eagle ray. Photos © Amber-Robyn Childs

So, what have we learned?

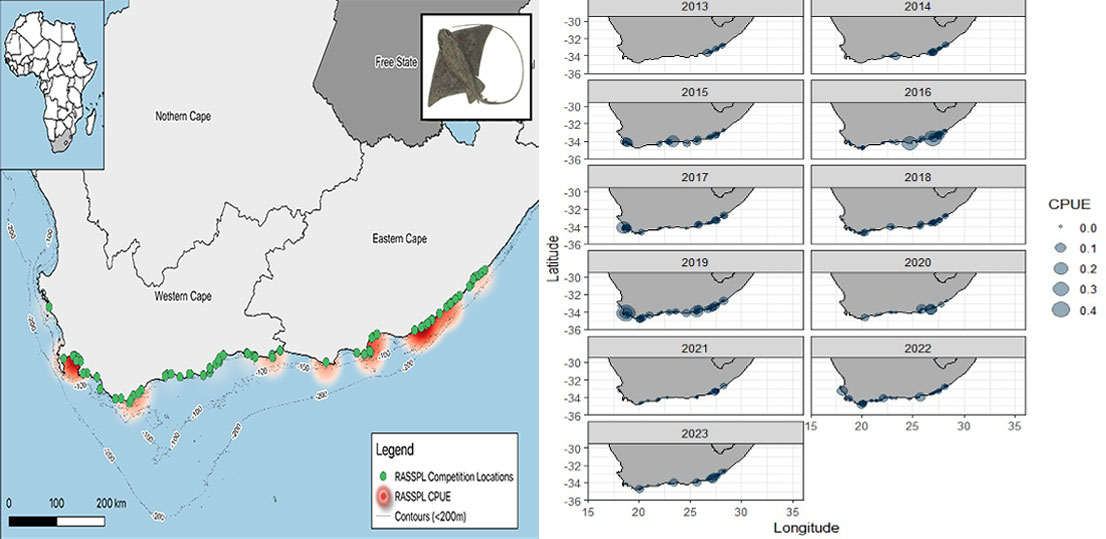

As part of the scientists’ and angler engagement through the RASSPL, we have developed a user-friendly scoring system database which documents the anglers fishing effort, catch by location, species and size over time. In our ten year old program, we have over 55541 catch records of different species between Langebaan and the Kei River mouth. Of these 244 were common eagle rays ranging in size from 26 – 94 cm DW (0.3 – 15.4 kg). On average only two eagle rays were caught every 100 angler days. In other words, angler fishing in these competitions have only a 2% chance of catching an eagle ray. Although this number is very small relative to the total catch records, this further highlights the utility of the scientists and angler engagement. From these data, we have been able to map the spatial distribution of the common eagle ray. The main catch hot spots this species were observed in False Bay and along the Sunshine Coast in the Eastern Cape (Kenton – Chalumna River) and to a lesser extent, in Algoa Bay with catches peaking between December and February (Figure 1). These patterns have also been consistently seen across the years (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Spatial patterns of the common eagle ray catch per unit effort based on data collected during the RASSPL competitions. Figure © Matthew Farthing, Alexander Winkler; Figure 2: Annual patterns from 2013 to 2023 for common eagle ray catch per unit effort based on data collected during the RASSPL competitions. Figure © Natanah Gusha

How will we use this information?

The information (particularly the spatio-temporal patterns of the common eagle ray) will be used for the conservation and management of this endangered species. For example, parts of the areas of high abundance of this species may be considered for conservation measures, while any changes in the catch rate (which is an indicator of abundance) can be used to update the IUCN assessment. In addition, the long-term catch and effort data can be used to develop a stock assessment for this species, which can, in turn be used to set better regulations in the fishery sector. Finally, this collaboration between scientists and recreational anglers illustrates dedicated knowledge co-development and the potential value of these joint projects as a pathway to a more sustainable future.