Recovered PSAT

By Julius Nielsen and Peter Bushnell

During the Greenland Shark Expedition in 2012, several Greenland sharks were tagged in the Ammasalik Fjord in south-eastern Greenland as part of a study on the migratory behaviour of the species. The tags used were pop-up satellite archival tags (PSATs), which are mini computers that measure temperature, depth and light levels over various time periods and then release from the shark on a pre-programmed date. After separating from the animal, the tag floats to the surface and broadcasts the stored data to satellites orbiting overhead. They in turn relay the data to a ground station, which e-mails them to the scientist.

Greenland sharks at the surface on a recovered long line. The sharks were caught on the bottom of the 500 m deep Ammasalik Fjord during fieldwork in 2012. Photo by: Julius Nielsen

One of the tagged sharks in 2012 was SM13, a 3.7-m sub-adult female. On 17 September she was caught on a long-line at a depth of 360 m and tagged with a PSAT that was programmed to record data over a nine-month period. In June 2013 the tag released from SM13 and transmitted data for six days before its battery died and it went quiet. From the data we received, however, we know this shark had been swimming mainly at depths between 300 and 400 m, where water temperatures ranged from -1 °C to 7 °C. The data also showed that on one occasion the shark had been as deep as 870 m.

The 3.7 m Greenland shark female, SM13, slowly swimming away after tagging with PSAT (right behind dorsal fin). 2,5 yr later the tag was found on a beach in Cornwall, England. Photo by: Anders Drud Jordan

In addition to the interesting data on swimming depth and temperature, a comparison between the GPS position of the tag (when at surface) and sea ice charts of the region revealed that at the time of the tag’s release the shark was swimming very close to the edge of the sea ice off the eastern coast of Greenland, where seals, fish and birds tend to congregate. As the Greenland shark is the largest predatory fish in the Arctic and fish and seals are among the main components of its diet, it was not surprising to learn that the shark was in this area. It was, however, very fortunate that we heard from the satellite tag at all, as we would not have received any signal if it had surfaced just a little further west under the ice.

Once the tag pops to the surface, the satellite’s GPS system typically allows us to track its position until it runs out of power. When this happened at the end of June in 2013 we did not expect to hear from the tag again. Luckily we were in for a surprise. In January 2015 Fiona Knight was walking her dog on a beach in Cornwall, southern England, when she noticed lying in the sand a small object that looked like a black cigar with an egg-sized float stuck on one end. This interesting piece of plastic was the PSAT of SM13, which had washed up in England after an 18-month, 2,200-km (straight- line) journey from where it had last been heard of off the coast of eastern Greenland.

The recovered PSAT found in Cornwall, England after its journey across the northern North Atlantic. Photo by: Julius Nielsen

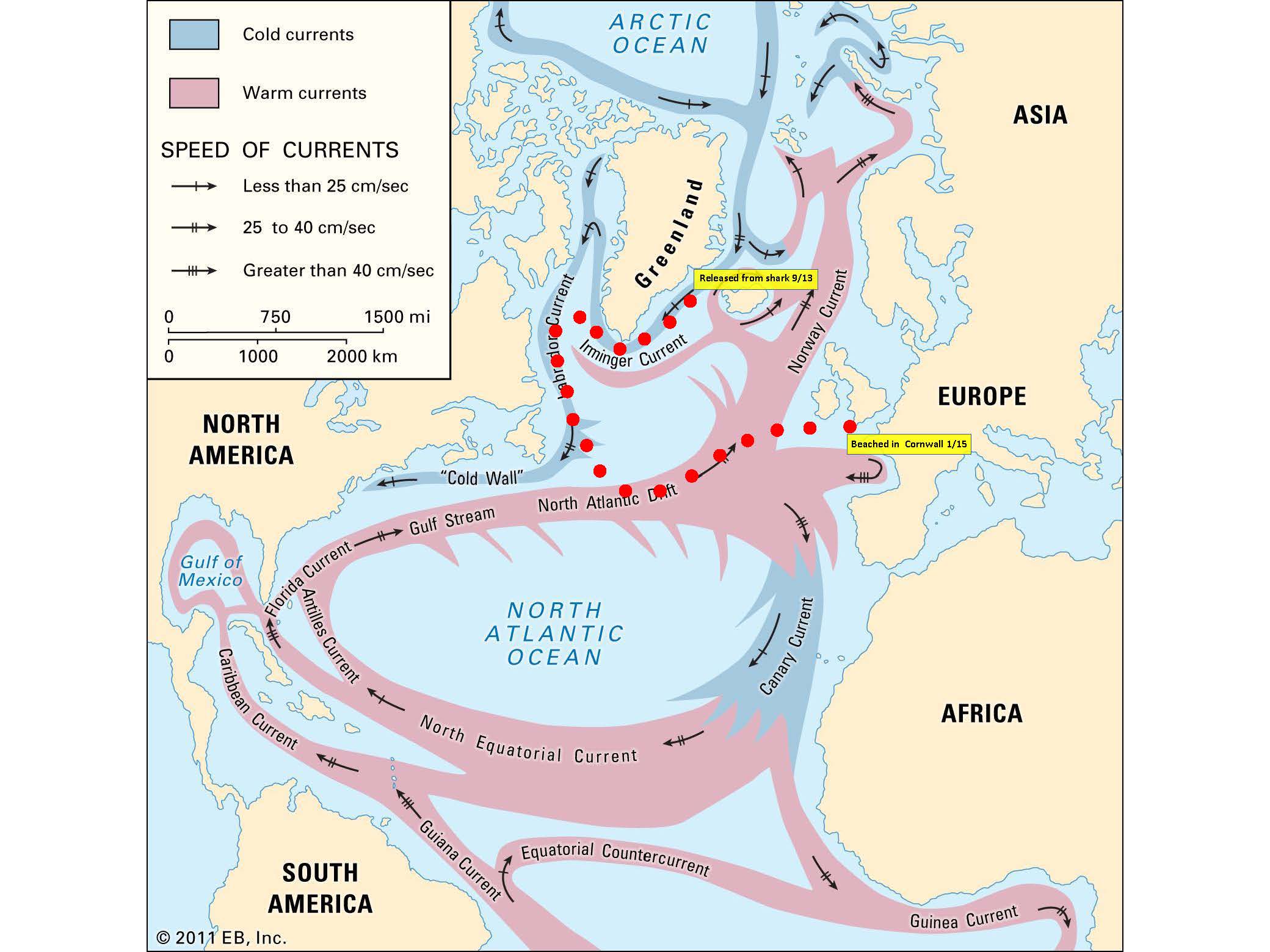

Given the surface current patterns around Greenland, we believe the drift track of the tag was much longer than the straight-line distance between Greenland and England. In order for the tag to end up in Cornwall, it was probably carried around the southern tip of Greenland by the Greenland Current and northward up the territory’s west coast. At some point the tag probably reached Canadian waters and was carried south in the Labrador Current along the eastern coast of Arctic Canada. Once in Newfoundland, it would have been close to the Gulf Stream, which would have borne it across the North Atlantic to southern England. Instead of 2,200 km, such a journey would have been more in the order of at least 6,000 km.

The most likely drifting pattern of the PSAT after release from the Greenland shark – a journey of at least 6000 km

Fiona’s fortuitous find of our PSAT is not just an interesting example of prevailing ocean currents. As the tag typically is not able to transmit all the data it has collected, we now have an opportunity to download the rest of the data it had saved in memory, which will give us a much better and more detailed look at what SM13 had been doing over the nine months the tag was monitoring her swimming activities. Finally, from a recycling point of view, we can have the tag refurbished and send it out on another adventure into the cold, dark world that Greenland sharks call home.