Pacific nurse sharks like to cuddle! But why?

Animals can benefit from aggregating in many ways: predator avoidance, cooperative feeding, reproduction, or environmental conditions. Aggregations can range from loose groups in the same general area to tight groups where individuals are in physical contact with each other. In Santa Elena Bay, in the north Pacific coast of Costa Rica, there is an intriguing case of these tight aggregations: Pacific nurse sharks (Ginglymostoma unami) form large groups (up to 50/60 sharks) in close proximity to each other in the shallow waters of the bay.

Largest Pacific nurse shark aggregation we observed in our study, consisting of 52 individuals. These sharks likely huddle together to conserve optimal body temperature during periods of upwelling when surrounding waters get much colder. Photo © Steven Lara

At first glance, we thought the aggregations of Pacific nurse sharks might be related to courtship and mating, as has been reported for their sister species, the Atlantic nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum), in the Caribbean. Researchers have found that female Atlantic nurse sharks form tight groups in shallow waters prior to copulation, while courting males approach during the breeding season. However, these two sister species have been evolving separately for millions of years, since the formation of the Central American Isthmus that separates the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Some aspects of their behaviour must have changed, right? Correct! In Pacific nurse shark aggregations, we have found that both males and females are present in the same group, and after many hours of drone surveys and underwater visual observations, we have not observed any courtship displays. It certainly appears that aggregations in the Pacific are not primarily driven by reproduction as in the Caribbean.

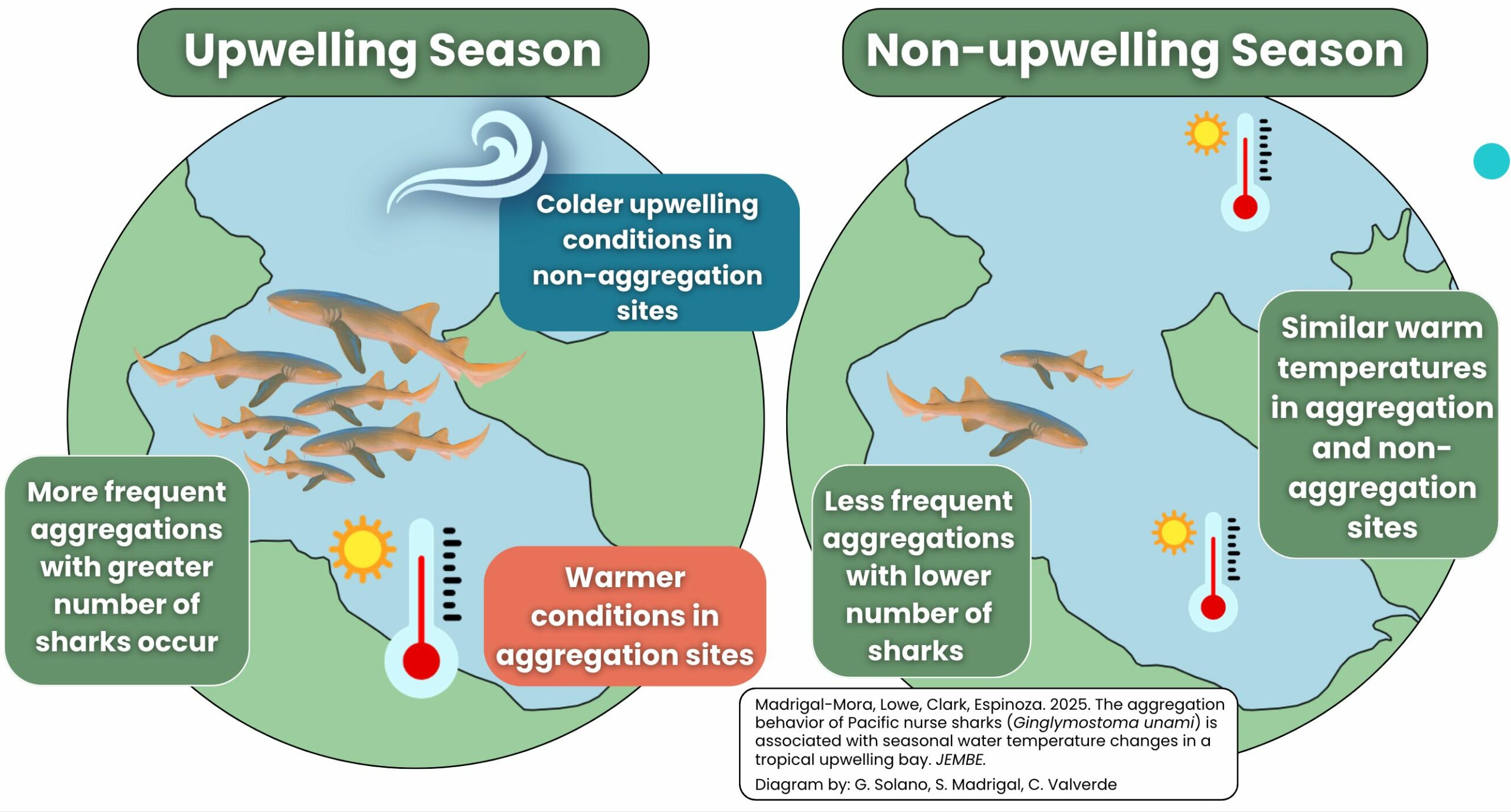

But what would be the point of these sharks aggregating for hours? We can discard the possibility of predator avoidance since previous studies have shown that predators of Pacific nurse sharks such as tiger sharks or bull sharks are very rare in the area. It is also unlikely to be related to prey availability, as there is no reason for the aggregation sites to be more productive than non-aggregation sites. Hence, we think the key may lie in the particular oceanographic conditions of the north Pacific of Costa Rica, a tropical upwelling region. Unlike the steady warmth characteristic of tropical waters, this region experiences dramatic shifts during the upwelling season (December to April). Strong trade winds draw cold, nutrient-rich water from the depths, causing surface temperatures to plummet from 28°C to as low as 16°C, which is quite cool for a traditional tropical environment.

Graphical abstract summarizing the findings of our study. Illustration © Sergio Madrigal-Mora

Using drone surveys and underwater temperature loggers, we found that aggregations were most frequent during the upwelling season, particularly when water temperatures were warmer than surrounding non-aggregation sites. Additionally, by grouping close together, and even on top of each other, individuals can conserve bodily heat, a behavior known as “huddling.” Therefore, it seems Pacific nurse sharks are better able to maintain optimal body temperatures when aggregating, which may improve their digestion, growth and reproductive development when waters become colder during upwelling. Furthermore, these aggregations may have a social component, as sharks usually return to the same specific area within aggregation sites. Our findings on the sociobiology of Pacific nurse sharks demonstrate how animals can be far more complex and even more similar to us than we generally think. As we discover more about their fascinating behaviors, understanding where, when and why animals aggregate is essential for the management and conservation of critical aggregation sites.

To complement drone surveys we photographed and recorded the aggregations underwater, where we observed that groups consist of both males and females. There were also many juveniles present alongside large adults. Since many of these individuals were too small to be sexually mature, it is unlikely that aggregations are associated with reproduction. Moreover, we have not observed any courtship or reproductive behavior in dozens of hours of drone footage, but only further monitoring will confirm this! Photo © Sergio Madrigal-Mora