On the road again…

Beep! Beep! Beep!

Bleary-eyed, I reach over to my alarm clock and swipe its insistent tone to silence. Its display blinks back at me in cheery, neon-green lights: 3.30 am. A quick yawn (and a brief struggle, willing my eyes not to close ‘for just one more minute!’) and I roll out of bed and into my gumboots. There is just enough time for a quick bowl of oats and banana, perhaps a spare second to gulp down a scalding brew of tea, before I load my equipment into my car and head off, headlights gleaming in the pre-dawn haze.

The view of an incredibly well-behaved False Bay as we leave Simon’s Town harbour and steam towards Roman Rock lighthouse in the Boulders no-take marine protected area. Photo: Kaspar Paur

This is the start of a typical day of field work for me in False Bay. After a few days, the still-starlit morning starts and the sun-soaked, nine-hour sea days begin to follow a routine as worn and vaguely comfortable as my boat work-gloves. We have to start early because many of my survey sites lie in the eastern- and southernmost reaches of the bay – a two-hour journey on our vessel if the wind is calm, maybe more if the conditions are tricky. So we find ourselves nursing mugs of steaming coffee and munching rusks as we steam past schools of common dolphins and the occasional Bryde’s whale to reach our first sites.

Focus! My final survey day saw an all-girl team working hard to achieve more than 40 deployments in a strong south-easterly wind. Here, Pippa Ehrlich of the CMU keeps the ropes from tangling as they are winched aboard, while field assistant Carrie Pretorius and I grab the jump camera before it slams into Sargasso’s gunwale. Photo: Ayesha Mobara

Deploying a camera to the sea floor more than 400 times in a temperate upwelling system involves a steep learning curve! False Bay’s location means several things for my field work. It’s situated at the confluence of the Agulhas Current and the Benguela upwelling system and is subject to variable winds. A strong north-westerly usually ‘cleans’ the bay, resulting in clearer water, and often brings rain; south-easterlies are more typical of summer and churn the bay into a white-flecked pea soup.

The sheer size of False Bay (at more than 1,000 square kilometres in extent, it is called South Africa’s largest true bay) means that the conditions in one part of it can be very different on the same day, at the same time, from conditions in another part. Inevitably this means that, despite my best attempts to follow every forecast available, we’ve still had days of working in challenging conditions. When swells higher than five metres roll towards Cape Point, I’ve learnt to time the hoisting of the camera between waves – just so! – so that the rig misses smashing into Sargasso’s gunwale. When the wind comes up early (which it has a nasty habit of doing, forecasts notwithstanding!) and starts gusting over 30 knots, we’ve learnt to hang onto each other (and our hats!), knees bent to sway with the boat as she pitches and rolls…

Selfie! Between deployments, Pippa and I tilt the jump camera to check that the GoPro camera is still taking photos. Using technology at sea inevitably makes for the odd glitch, and after my camera switched itself off and failed to take photos at 20 sites, I learned very quickly to check that it is still working after every descent to the sea floor.

Two nail-biting months after I started, I’ve completed the first GoPro jump camera survey of False Bay’s invertebrate populations and am now starting to sift through hundreds of photographs for analysis. I’d certainly never envisaged myself doing the work of an invertebrate ecologist, but my curiosity about how the various trophic levels interact only grows the more time I spend surveying False Bay. If I’ve learnt anything, it’s that taking an interest in ecology is like opening Pandora’s box – you never finish pondering questions and puzzling over new finds. Undoubtedly, the marine invertebrates (that is, those species without a backbone – think of creatures as diverse as octopuses, anemones, sea stars and mussels) are key to understanding why the various fishes are distributed around the bay in particular patterns. Investigating questions like these – layer by layer – ultimately gives me more information with which to understand the sharks, rays and skates of False Bay too.

Red tide! No matter the amount of planning and preparation, field work still involves a good dose of luck. On this day, the sea conditions were perfectly flat and the warm sunshine made for a fun day out – but we could not have foreseen these surface blooms of dinoflagellates!

A camera survey of invertebrates does, of course, have its limitations. Most obvious is the fact that I can’t detect what’s in the water column, and the accurate identification of the visible macro (large), benthic (sea-floor) species relies on good camera resolution. I’m looking forward, however, to assessing how this technique fits in as an additional tool in our existing arsenal for biodiversity monitoring – and it will certainly allow me to detect species from key invertebrate groups in the bay. Once again, we’re trying to keep the technology practical enough for use by other conservation practitioners, so that monitoring like this is not limited to scientists but can be carried out by managers and rangers all along the coastline. Maintaining the balance between best-quality science and extending capacity along a resource-strapped coastline is something I think South Africans are pretty good at – and it’s something I’m passionate about contributing to!

Elegant featherstars Tropiometra carinata and noble corals Allopora nobilis live up to their name and make for a pretty display, dominating this patch of reef near Rooi Els in the east of False Bay. This region comprises predominantly shale rock and it is my absolute favourite area to survey the startling array of invertebrate life. Photo: Lauren De Vos

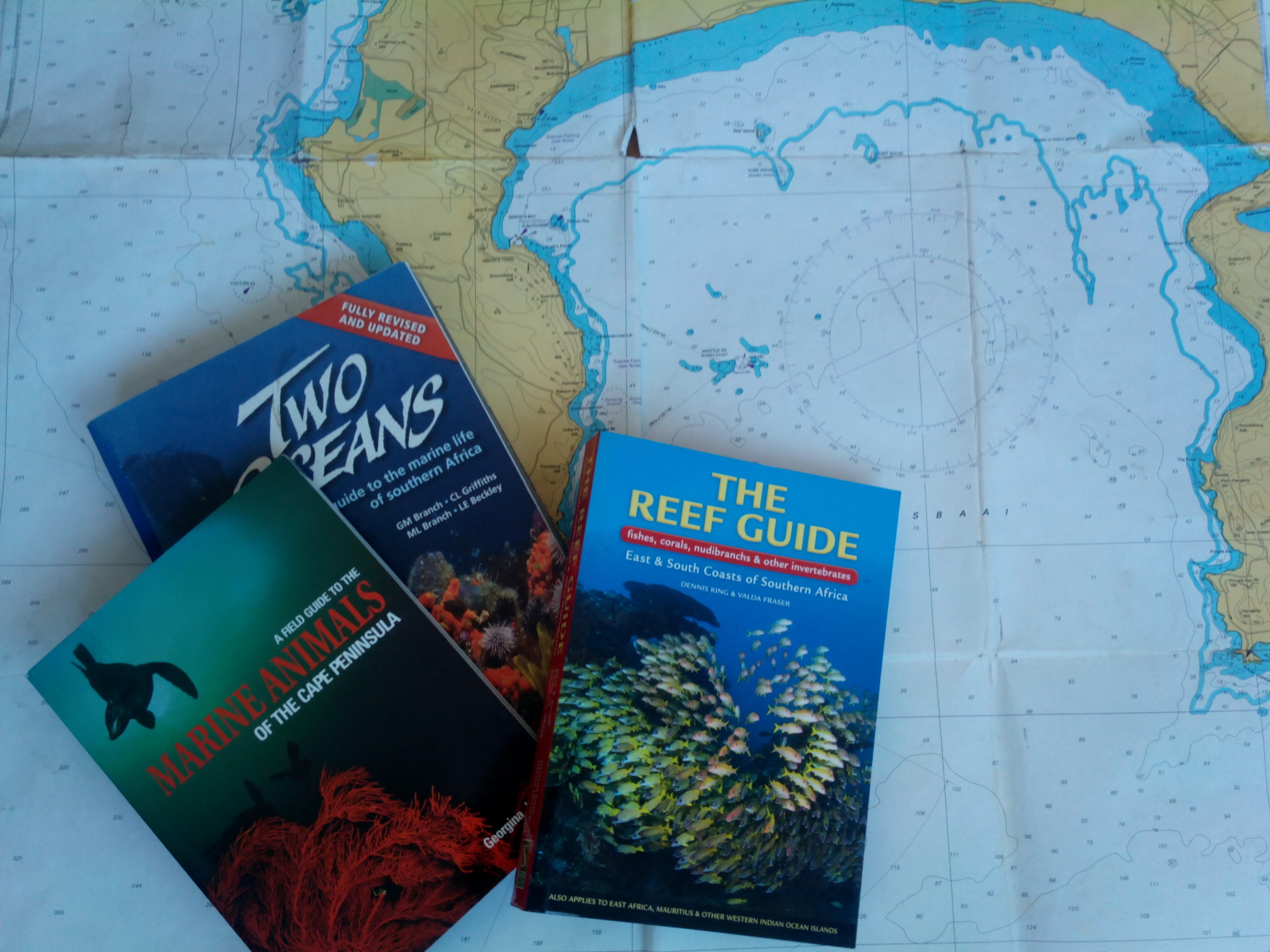

So the next few weeks will see me extending my biological vocabulary to include velvety coralline crust Heydrichia woelkerlingii and Cape urchin Parechinus angulosus – a daunting task, but hopefully one of my next posts will soon have me sharing what I’m finding, and where, and under what circumstances. With well over 50 fish species for the region under my belt, I’m keen to challenge and extend my camera identification repertoire! In the meantime, I’m off to read Marine Animals of the Cape Peninsula. Cup of tea, anyone?

Recommended reading: the analysis phase inevitably sends me back to the books. The advantage of photographic records, aside from the archive it provides for long-term assessments of environmental change, is that I can send troublesome identifications to other scientists for their expert opinions! Photo: Lauren De Vos