My chemical romance

The word ‘contaminant’ brings to mind different ideas depending on who you’re talking to: dirty, dangerous, disaster. My work focuses on measuring what are called ‘legacy organic contaminants’ in elasmobranchs (sharks, rays and chimaeras). Many of the compounds I am interested in studying are, however, not in the public eye, even though my own marine backyard – California – is one of the largest hotspots for these contaminants.

Many tons of organic contaminants were released into the southern California marine environment before they were banned in the 1970s. © Photo by Kan Khampanya | Shutterstock

Let me break down what I mean by ‘legacy organic contaminants’.

Legacy

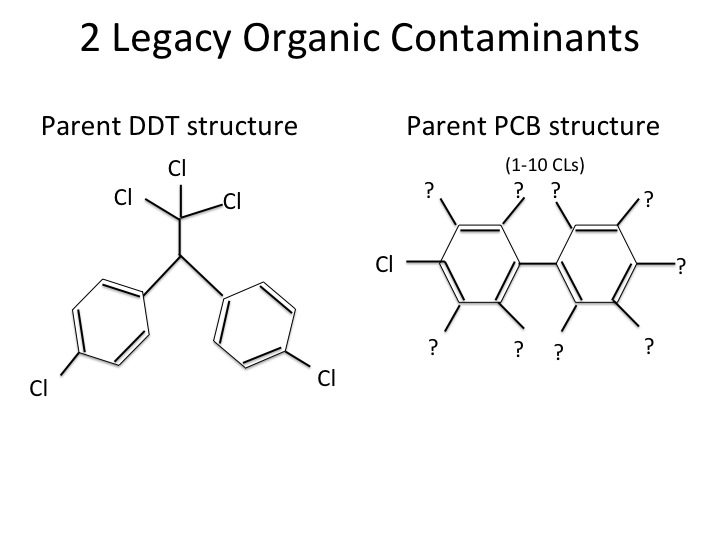

This means that most of the substances I study are chemicals that were produced a long time ago and are now banned from being produced or released in most, if not all, parts of the world (depending on the compound). For instance, it has been illegal to manufacture polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) since the 1970s. However, their chemical structure and design are such that these compounds continue to persist in the environment even though they haven’t been produced for decades!

Organic contaminants

In the modern lexicon, organic is often synonymous with healthy or natural, but in fact organic compounds are ones that have carbon backbones. Organic contaminants, which are neither natural nor healthy, usually – but not always – have some sort of halogen (that is, chlorine, fluorine, bromine) attached to them. Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (that’s a mouthful, but it’s more commonly known as DDT), for instance, has two carbon rings with various chlorine atoms attached, and it has been shown to have a disastrous impact on the environment.

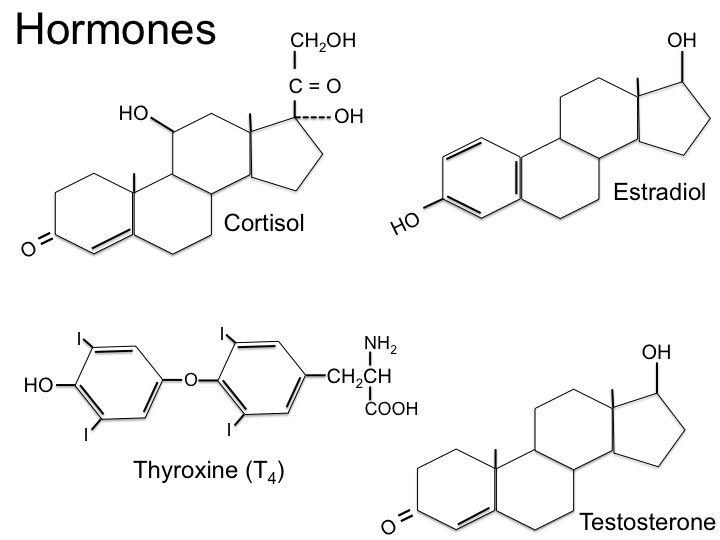

DDT and PCBs (A) share a similar carbon ring structures with several important hormones (B) Because of this similarity, organic contaminants can interfere with hormone signaling and disrupt normal functioning. © Kady Lyons

DDT and PCBs (left panel) share a similar carbon ring structure with several important hormones (right panel). Because of this similarity, organic contaminants can interfere with hormone signalling and disrupt normal functioning.

Top predators such as tuna, polar bears, dolphins and sharks can have the highest levels of legacy contaminants in their tissues. © Photo by Christopher Wood | Shutterstock

Because of their structure, organic contaminants are ‘fat-loving’ and like to build up in tissues that are high in lipids, such as adipose, blubber (in marine mammals) or liver. Unlike heavy metals, which are inorganic (meaning they have no carbon structure associated with them), organic compounds can biomagnify, which means that the concentration of these chemicals increases as you move up the food chain. (When you hear about mercury accumulating in marine predators, like sharks and tuna, it’s actually methylated mercury that they’re talking about. Each methylated mercury molecule has an organic component associated with it, so it can biomagnify.) Therefore, our top predators such as tuna, polar bears, dolphins and sharks can have the highest levels of these contaminants in their tissues.

In addition, the structure of organic contaminants makes them prone to targeting biological systems, which disrupts the physiology of animals and produces negative effects. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, published in 1962, was one of the first books to draw the public’s attention to the negative impacts of pesticides on bird health and ultimately spurred the government to ban the use of DDT in the USA.

In the early 1960's Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring reported that birds ingesting DDT tended to lay thin-shelled eggs which would in turn break prematurely in the nest, resulting in marked population declines The problem drove bald eagles to the brink of extinction, with populations plummeting more than 80 percent. © Photo by Chris Hill | Shutterstock

You might well ask, ‘If these things are so dangerous, why were they made in the first place?’ An excellent question. Many of these compounds were designed for specific purposes, but it wasn’t until after they were made and put to use that their negative impacts on the environment were realised. For example, DDT is an extremely potent pesticide that played a role in reducing malaria and typhus deaths in World War II, and it is still used as a vector control chemical in certain parts of the world. PCBs were used as an industrial lubricant because they could resist high temperatures.

Top predators such as tuna, polar bears, dolphins and sharks can have the highest levels of legacy contaminants in their tissues. © Photo by Byron K. Dilkes | Shutterstock

So if we have seen that legacy organic contaminants are bad for birds, reptiles, bony fishes and mammals (including us humans!), what do these compounds do in elasmobranchs? To answer this question, we must first understand the dynamics of contaminant accumulation, which can vary depending on the species, sex and age of the animal. Part of my research involves examining the differences between species that will build the foundation for digging deeper into the potential effects the compounds have on elasmobranch health.