More than neighbours

Most people are aware of the important role that sharks, as top predators, play in the ecosystem, but they are also amongst the most threatened, with fishing being the greatest man-made threat. As such, improved management of this group as a whole is of utmost importance, yet sharks are highly mobile, moving where they want and rarely sticking to jurisdictional boundaries. This makes management of these animals all the more difficult.

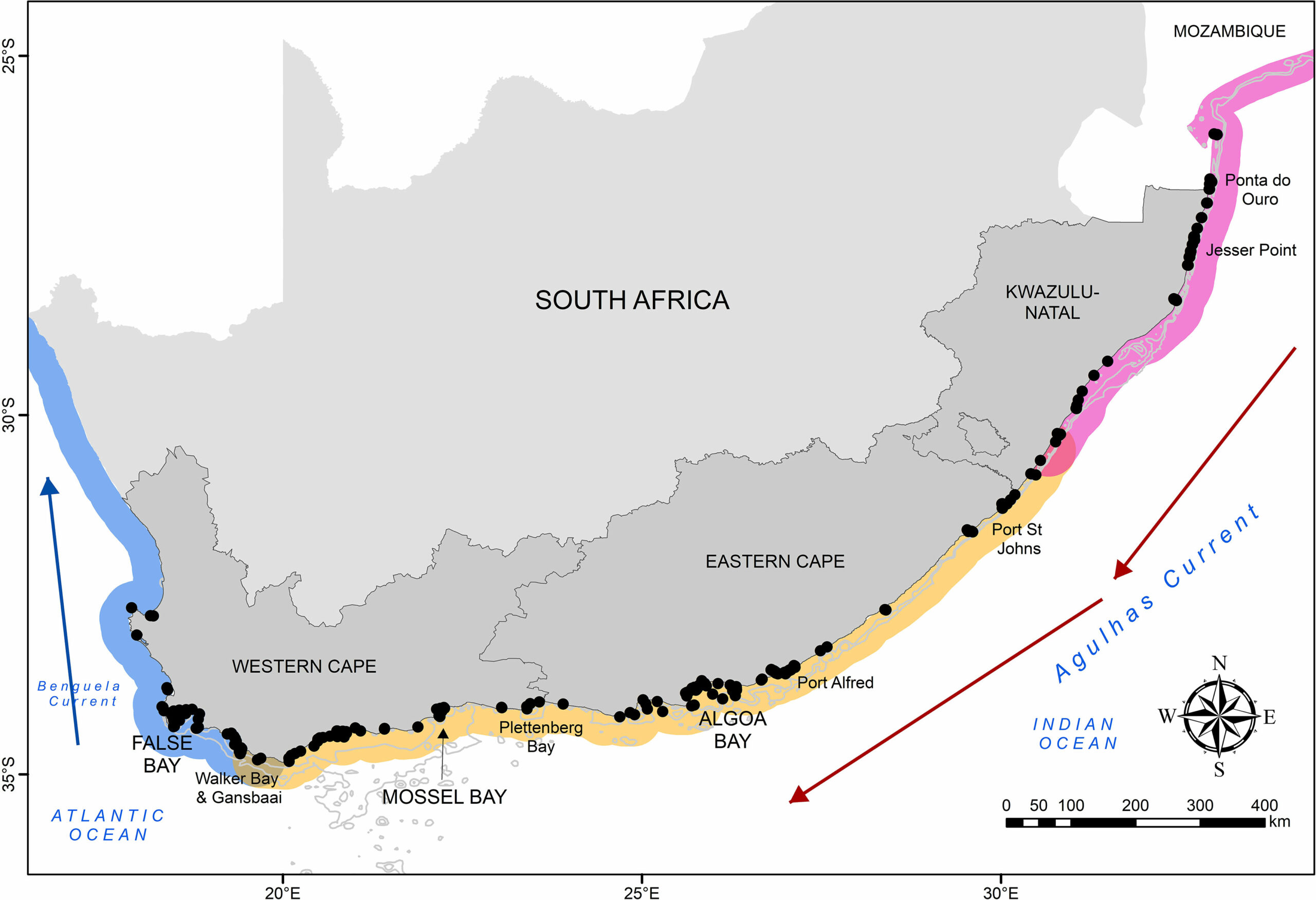

Tracking animals provides the movement data needed for improved management, and given a good spread of acoustic receivers in neighbouring countries, particularly near the borders, researchers can get a better understanding of how often animals are moving between countries. This is exactly what was highlighted in a recent paper led by previous SOSF project lead Dr Ryan Daly, Oceanographic Research Institute Scientist, where four shark species – bull, blacktip, grey reef and tiger – were acoustically tagged in South Africa and southern Mozambique, and movements were monitored for four years (2018-2022) by the Acoustic Tracking Array Platform (ATAP) – a large-scale network of acoustic receivers covering ~2200 km/1370 miles of the South African and southern Mozambique coastline. Additional small-scale receiver arrays in southern Mozambique, from Zavora to Bazaruto, were maintained by Marine Megafauna Foundation (MMF), and data collected from these receivers were collected and compiled in collaboration with MMF and Oceans Without Borders.

The locations of receivers (black dots) forming the greater Acoustic Tracking Array Platform currently deployed along the South African coastline. Image from https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.886554

Of over 100 animals tagged, 69% were recorded moving between South Africa and Mozambique, but to varying degrees. For example, only 25% of tagged grey reef sharks made these movements compared to 94% of tagged tiger sharks, where tiger sharks, on average, made 7.5 trips between the two countries every year. Time of year and associated season also influenced the presence of sharks in both countries. For example, although bull sharks were detected close to the South African-Mozambican border throughout the year, modelling results showed sharks to move from South Africa to Mozambique in winter, making a return migration during summer months. Blacktip sharks, on the other hand, appeared to do the opposite, mostly remaining in subtropical and tropical reaches of South Africa and Mozambique during summer, but moving southwards into temperate South African waters in winter.

Bull shark. Photo © Stèphane Rochon | Shutterstock

So what does this all mean? Firstly, all data collected provided new insights into the transboundary movements of these species, something previously unknown. This study also emphasizes the need for cooperative management between South Africa and Mozambique, especially when the needs between the two countries differs so drastically. For example, dive tourism associated with tiger sharks in South Africa is worth ~US $ 660 000 per year, but across the border, tiger sharks can fall victim to the shark fin trade, and illegal, unregulated and unreported fisheries.

This new study wrapped up with some regional- and binational-scale recommendations for improved management of these, and other important shark species, something that will hopefully be taken on board.