Mobulids of the Azores: Introduction to species morphology and behaviour

The Azores Archipelago provides refuge for a wide range of migratory species from cetaceans to seabirds to elasmobranchs. The shear variety and number of charismatic marine organisms attracts the attention of wildlife enthusiasts everywhere. During the summer months Princess Alice Bank becomes a hotspot for divers and snorkelers eager to encounter one of the most charismatic species found in the region, the sicklefin devil ray (Mobula tarapacana). However, divers may also encounter other mobulid species such as oceanic mantas, Mobula briostris, and spinetail devil rays, Mobula mobular.

In recent years scientists have utilised a wide range of tools to characterise the population dynamics and distribution of mobulids in the Azores. Projects such as Manta Catalog Azores encourage visitors to participate in citizen science by submitting photos and videos from their encounters. This information is used by researchers to better understand the seasonal dynamics of mobulid populations in the Azores using photo-ID. Here we merely scratch the surface regarding the morphology and behaviour of M. tarapacana, M. mobular and M. birostris. Despite their many similarities these mobulid species have a wide range of morphological and behavioural characteristics that can be used for identification.

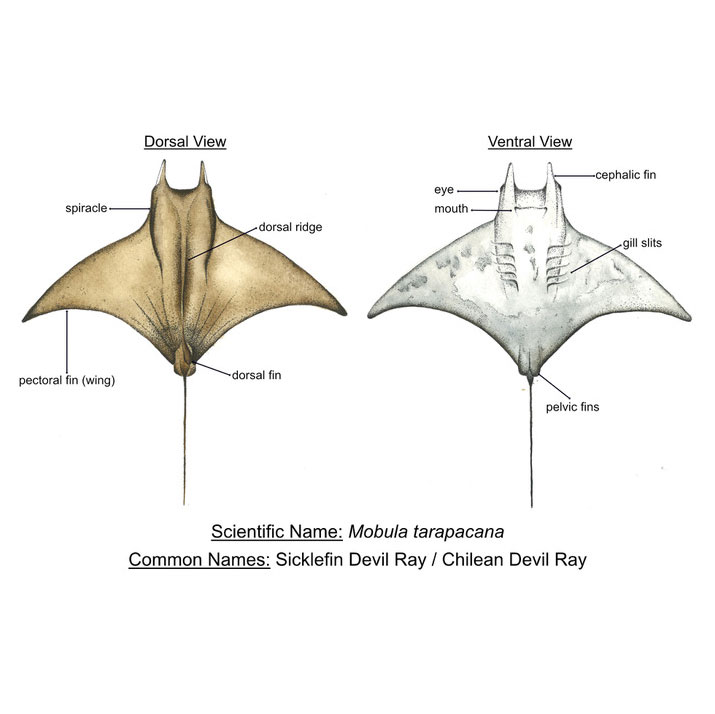

The sicklefin devil ray (M. tarapacana). Artwork © Dr. Clemency White

Morphology

Sicklefin devil rays are easily identified by their distinct olive-green/ brown dorsal colour and sickle shaped pectoral fins (wings), the result of a more rounded anterior (front) margin and more concave posterior (back) margin, compared to species such as the spinetailed devil ray. Their ventral side is white with distinct grey markings, similar in appearance to those on oceanic mantas. As one of the larger mobulid species, M. tarapacana reaches up to 370 cm from wingtip to wingtip (also referred to as their disc width) (White et al., 2018). Sicklefin devil rays have a short thick tail with no tailspine (Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, 1987). Other identifying characteristics include a longer narrow head, short cephalic fins (used to direct water into their mouth when feeding), a pronounced dorsal ridge along their midline, and a sub-terminal mouth (Chandrasekaran et al., 2022; Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, 1987).

Behaviour

Sicklefin devil rays are generally regarded as a solitary species, however during the summer months groups between 3 – 50+ gather at the Princess Alice Seamount, southwest of Faial Island, and the Ambrosio Seamount, near Santa Maria Island. Here individuals are seen feeding, courting potential mates, and socialising (Das & Afonso 2016). Feeding behaviour is evident when the rays’ cephalic fins are unfurled with their mouth open coupled with an increase in speed or a sharp downward turn (Solleliet-Ferreira et al., 2020). Sicklefin devil rays are curious, often swimming very close to divers. When they are not cruising at the surface this species has been found to make frequent excursions to the bathypelagic realm, reaching depths of up to 1,800 meters (Thorrold et al., 2014).

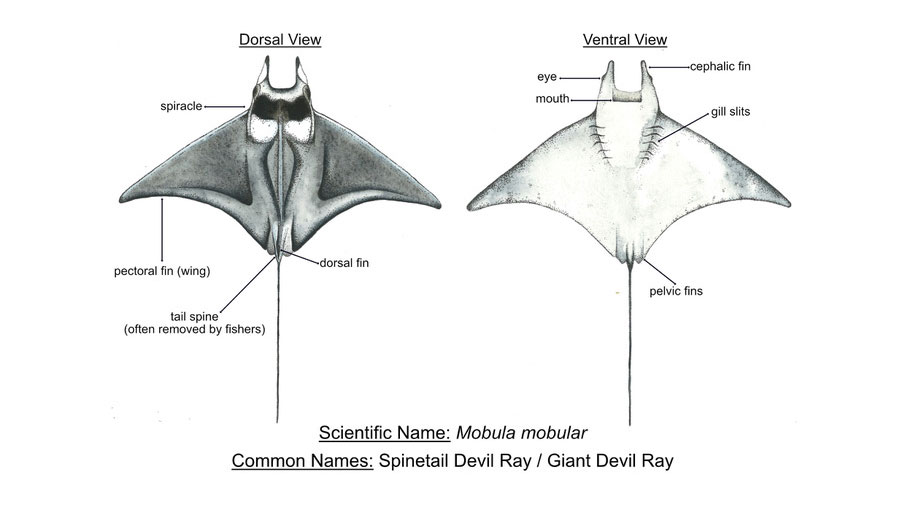

The spinetail devil ray (M. mobular). Artwork by Dr. Clemency White

Morphology

The most distinguishing feature of the spinetail devil ray, Mobula mobular, is its long whip-like tail, complete with a serrated spine at the base of the dorsal fin (Notarbartolo di Sciara et al., 2020). They are also identified by the thick black band that stretches across the width of the head, from eye to eye. Their dorsal surface is dark blueish grey in colour with light grey/ white patches atop each “shoulder” (Stevens et al., 2018). Though their colouration is similar to that of oceanic mantas, spinetail devil rays are distinguished from their relative by their narrow head, short cephalic fins, and sub-terminal mouth (characteristics attributed to all devil ray species). Their ventral surface is mostly white with light grey markings towards the tips of each wing (Stevens et al., 2018). The maximum size of this species has been a highly debated topic for many years; however, recent studies confirm their maximum disc width to be 350 cm from wingtip to wingtip (Notarbartolo di Sciara et al., 2020).

Behaviour

Spinetail devil rays spend most of their time in warm surface waters (top 50m) but will dive to depths of up to 1,112m (Canese et al., 2011). Like sicklefin devil rays, spinetail devil rays generally travel alone or in small groups, however large aggregations are known to occur albeit in the Mediterranean off the coast of Palestine (Abudaya et al., 2018). In the Azores sightings of this species are rare. Spinetail devil rays have also been known to breach, leaping high above the ocean’s surface, however, the purpose of this behaviour remains unclear (Palacios et al., 2024).

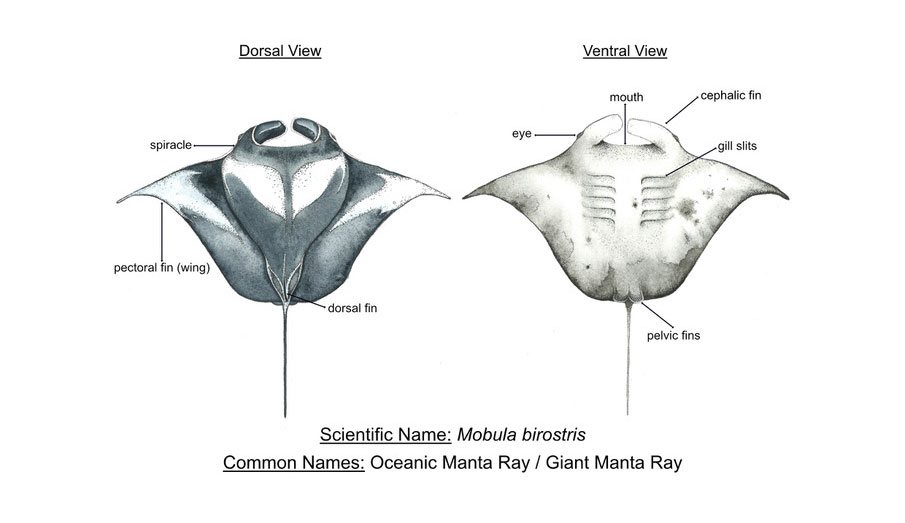

The oceanic manta ray (M. birostris). Artwork by Dr. Clemency White

Morphology

The oceanic manta, Mobula birostris, the largest species of mobula, can have a disc width of up to 700cm (Compagno, 1999). Aside from the sheer size of mature individuals, oceanic mantas can be distinguished from other mobulids by their terminal mouth (positioned at the front of the head) and paddle like cephalic fins (White et al., 2018). They have a thin whip like tail, similar to that of M. mobular, however their tail is shorter than their disc width and their tailspine is encased in calcified mass at the base of their dorsal fin (White et al., 2018). Their dorsal surface is generally black with white triangular markings on each “shoulder” and additional white streaks at the tips of each pectoral fin. Their ventral surface is white with grey and black markings towards the abdominal region and their cephalic fins (White et al., 2018). However, although they are rare, two additional colour morphs have been identified for this species. Melanistic mantas have a completely black dorsal surface, and their ventral surface is almost entirely black, aside from white patches along the midline that vary in size (Marshall et al., 2009). Leucistic mantas are the opposite, these individuals have less pigmentation and are therefore significantly lighter in colour (Stevens, 2016).

Behaviour

Individuals sighted in the Azores are mostly solitary, although the species is known to aggregate in areas with upwelling currents at continental margins and offshore (Marshall et al., 2009). However, smaller mobulid species have been observed following the larger oceanic mantas when they appear at regional seamounts. Oceanic manta sightings are less common than those of sicklefin devil rays, yet they are sighted more often than spinetail devil rays (Sorbal, 2013; Sorbal & Afonso 2014). Like other mobulid species M. briostris are curious and will occasionally approach divers.

**References

Abudaya, M., Ulman, A., Salah, J., Fernando, D., Wor, C. and di Sciara, G.N. (2018) Speak of the devil ray (Mobula mobular) fishery in Gaza. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 28, pp.229-239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-017-9491-0

Chandrasekaran, K., Dhinakarasamy, I., Jayavel, S., Rajendran, T., Bhoopathy, S., Gopal, D., Ramalingam, K. and Khan, S.A. (2022) Complete sequence and characterization of the Mobula tarapacana (Sicklefin Devilray) mitochondrial genome and its phylogenetic implications. Journal of King Saud University-Science, 34(3), p.101909. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0224-2020-0008

Compagno, L.J. (1999) Systematics and body form. Sharks, skates and rays: the biology of elasmobranch fishes, pp.1-42.

Das, D. and Afonso, P. (2017) Review of the diversity, ecology, and conservation of elasmobranchs in the Azores region, mid-north Atlantic. Frontiers in Marine Science, 4, p.354. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00354

Francis, M.P. and Jones, E.G. (2017) Movement, depth distribution and survival of spinetail devilrays (Mobula japanica) tagged and released from purse-seine catches in New Zealand. Aquatic Conservation, 27(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2641

Marshall, A.D., Compagno, L.J. and Bennett, M.B. (2009) Redescription of the genus Manta with resurrection of Manta alfredi (Krefft, 1868)(Chondrichthyes; Myliobatoidei; Mobulidae). Zootaxa, 2301(1), pp.1-28. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2301.1.1

Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, G. (1987) A revisionary study of the genus Mobula Rafinesque, 1810 (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae) with the description of a new species. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 91(1), pp.1-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1987.tb01723.x

Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, G. (1988) Natural history of the rays of the genus Mobula in the Gulf of California. Fishery Bulletin, 86(1), pp.45-66.

Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Stevens, G. and Fernando, D. (2020) The giant devil ray Mobula mobular (Bonnaterre, 1788) is not giant, but it is the only spinetail devil ray. Marine Biodiversity Records, 13(1), pp.1-5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-020-00187-0

Palacios MD, Trjo-Ramírez A, Velázquez-Hernández S, Huesca-Mayorda SAK, Stewart JUD, Cronin MR, Lezama-Ochoa N, Zilliacus KM, González-Armas R, Galvan-Magaña F, Croll DA (2024) Reproductive behavior of three mobulid species (Mobula mobular, Mobula thurstoni and Mobula munkiana) in the Southern Gulf of California, Mexico. Mar Biol 171:12

Solleliet-Ferreira, S., Macena, B.C.L., Laglbauer, B.J.L., Sobral, A.F., Afonso, P. and Fontes, J., (2020) Sicklefin devilray and common remora prey jointly on baitfish. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 103, pp.993-1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-020-00990-9

Stevens, G., Fernando, D. and Di Sciara, G.N. (2018) Guide to the Manta and Devil Rays of the World (Vol. 13). Princeton University Press.

Stevens, G.M.W. (2016) Conservation and population ecology of manta rays in the Maldives (Doctoral dissertation, University of York).

Thorrold, S.R., Afonso, P., Fontes, J., Braun, C.D., Santos, R.S., Skomal, G.B. and Berumen, M.L. (2014) Extreme diving behaviour in devil rays links surface waters and the deep ocean. Nature communications, 5(1), p.4274. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5274

White, W.T., Corrigan, S., Yang, L.E.I., Henderson, A.C., Bazinet, A.L., Swofford, D.L. and Naylor, G.J. (2018) Phylogeny of the manta and devilrays (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae), with an updated taxonomic arrangement for the family. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 182(1), pp.50-75. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlx018