Manta detectives in Baa Atoll

The Maldives Manta Conservation Programme team at our research base in Baa Atoll experience a hectic seven-month season of manta-madness, recording around 5,000 reef manta ray sightings each year. From our dedicated research vessel, we collect manta ray photo-identification images and survey data from Hanifaru Bay Marine Protected Area and 15 other sites around the atoll. This extensive data collection, conducted over the last two decades, has helped us notice and keep track of patterns in many different aspects of Baa Atoll’s reef manta rays, like seasonality, site use, and reproductive habits.

Maldives Manta Conservation Programme researchers aboard our dedicated research vessel moored up in Hanifaru Bay Marine Protected Area. Ready to get those photo-IDs! Photo © Flossy Barraud

Despite the Maldives reef manta ray population being one of the most intensively studied in the world, there’s still so much we are yet to understand and uncover. While we feel lucky to be able to spend six days a week observing and studying these fascinating animals in the field; year-on-year, we are continually surprised and intrigued by changes in their habits and behaviours. This season and last, the Baa Atoll manta rays have certainly kept us on our toes, with sightings not quite following the expected patterns we have grown accustomed to.

A quick check to make sure our equipment is tucked up safe and sound on the seafloor. Photo © Matthew Gledhill

During the Southwest Monsoon (Hulhangu) in Baa Atoll, it is well known among scientists, community members, and tour operators that around the full and new moon of each month is when reef manta ray sightings are at their peak. Tens, or even hundreds, of hungry manta rays aggregate to exploit the ‘buffet-style’ concentrations of their zooplankton prey in Hanifaru Bay. The days encompassing the full or new moons, so-called manta ‘hot dates’, draw hundreds of eager snorkellers from resorts, guesthouses, and liveaboards each day in anticipation of these spectacular mass feeding events.

Smiling faces after successfully retrieving some of our equipment from the seabed. Now for some TLC and maintenance before they are deployed again. Photo © Yoosuf Abdulla Haadhee

However, these manta ray ‘hot dates’ don’t always live up to their name! While the days leading up to the full or new moon have given us fruitful sightings of mass feeding this season; when visiting Hanifaru on the ‘moon day’ itself and thereafter, our expectant researchers and Baa’s tourists alike have been surprised to find an all but empty Bay, with not a feeding manta ray or copepod in sight. Although this isn’t always the case, these quieter moons certainly have our researchers scratching their heads.

Preparing our equipment for a six-month deployment, aka. gently applying cream to the sensors to keep biofouling at bay (and giving it a pep talk). Photo © Tiff Bond

A similar mystery is the early end to the ‘Manta Season’ in 2023. While the season typically runs from May through November in Baa Atoll, November 2023 saw the lowest number of manta ray sightings on record – just 15 across the whole month! This number is in contrast with previous years, most notably November 2020 during which sightings soared to a whopping 1,991 (the highest monthly total on record to date).

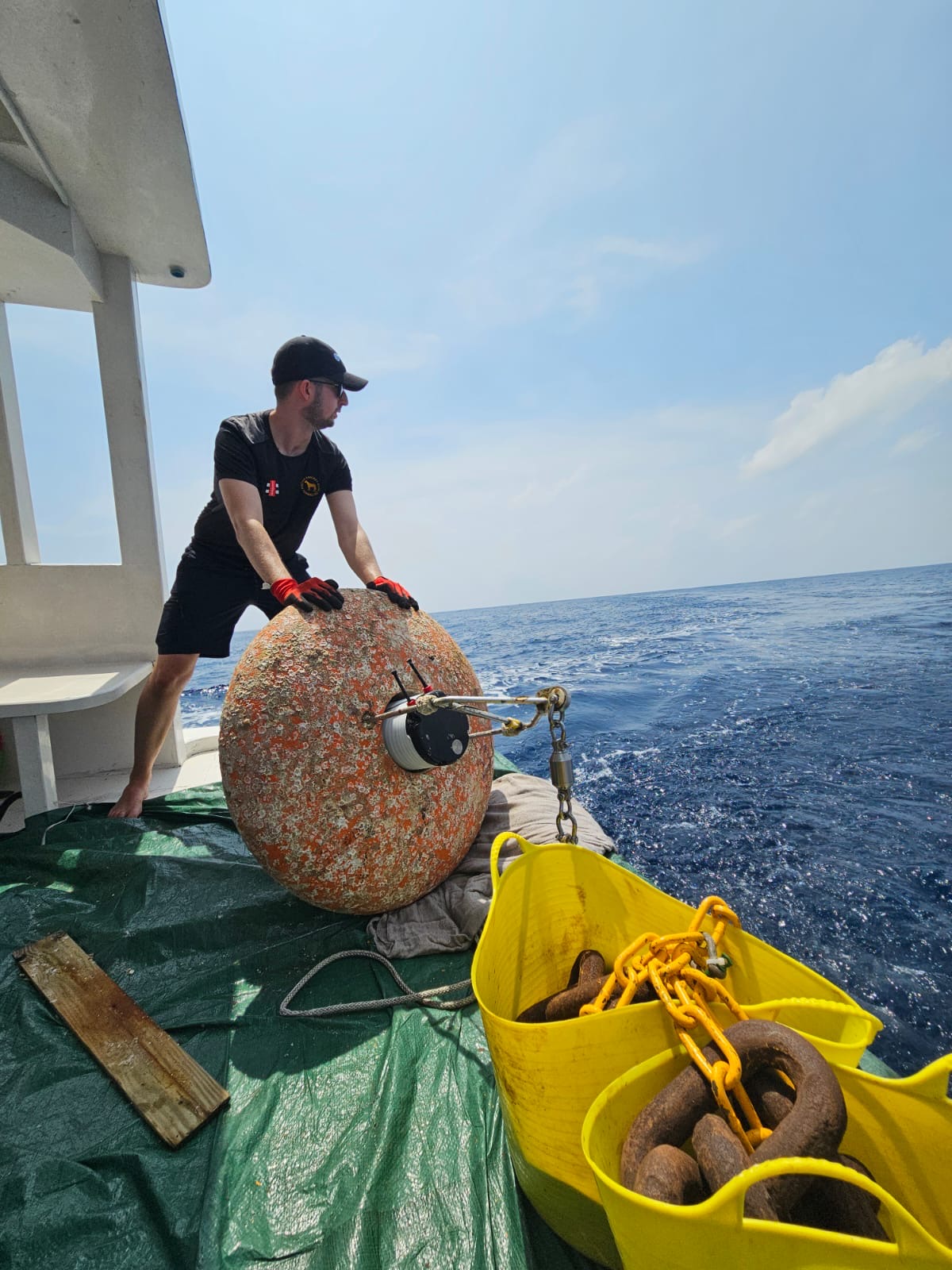

Ready to lower our (very heavy) equipment into the water, with the help of our trusty freediving buoy to lighten the load. Photo © Elspeth Strike

These puzzling happenings, to name only a few, have raised exciting questions we hope to be able to answer through our ongoing research. Why do sighting numbers and site use vary so much year-on-year? What drives mass manta ray feeding aggregations in Hanifaru Bay? Why are our manta ‘hot dates’ sometimes not so hot?

The key to trying to answer these questions, we hope, will be our long-term oceanography study, led by Dr. Phil Hosegood from the University of Plymouth. This is a three-year collaborative study between the University of Plymouth, Manta Trust, Maldives Environmental Protection Agency, Four Seasons Resort at Landaa Giraavaru, and the Bertarelli Foundation.

The opposite of “Anchors Aweigh!” - this equipment is ready to spend six months at 50m on the seafloor, collecting data on the currents flowing across Baa Atoll. Photo © Tiff Bond

Put simply, this field work, think of it like manta detective work, involves lowering (very heavy) oceanographic equipment onto the sea floor (an undercover spy, if you will) for several months, and then bringing it back up covered in barnacles and full of the ocean’s secrets (namely, data on the currents, temperature, and plankton distribution). This work, coupled with mapping the Bay’s unique underwater landscape, will help us to uncover the ideal environmental (wind, rain, weather) and oceanographic (currents, tides, lunar phase, swell) drivers for zooplankton concentration in Hanifaru Bay, and indeed across wider Baa Atoll.

Covered in barnacles, bio-foul, and full of the ocean’s secrets. After six months at depth, we’re ready to clean, maintain, and download the data before this equipment is ready for its next mission. Photo © Elspeth Strike

So, why is this work so important? With this knowledge, we can better understand why manta rays aggregate in Hanifaru when they do, and why they (sometimes) disappear for extended periods during ‘Manta Season’. On a broader scale, it will also help us to explain how manta ray behaviour corresponds to oceanographic conditions across Baa Atoll.

Looking to the future, if we can identify and understand these key baseline mechanisms, we can better monitor this critical habitat over time and track how the climate crisis might impact the manta rays of Baa Atoll, and beyond.

A spectacular mass feeding event in Hanifaru Bay Marine Protected Area