‘Lost’ sharks of Rapa Nui? Not any more!

Easter Island, also known by the Polynesian name Rapa Nui, is a mysterious place hidden in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Located 2,100 kilometres (1,300 miles) east of the Pitcairn Islands, the nearest inhabited archipelago, Rapa Nui is considered to be the most isolated inhabited island and to have the south-easternmost coral reef system in the Pacific Ocean. The island is well known for its ancient stone statues, called moai, and has more recently come into the news for its high level of endemism (animals and plants which are unique to the island), a level that can only be compared with that of the Hawaiian archipelago.

These monumental stone statues, or moai, represent ancient Rapa Nui royalty or spirits. Photo © Ivan Hinojosa | ESMOI

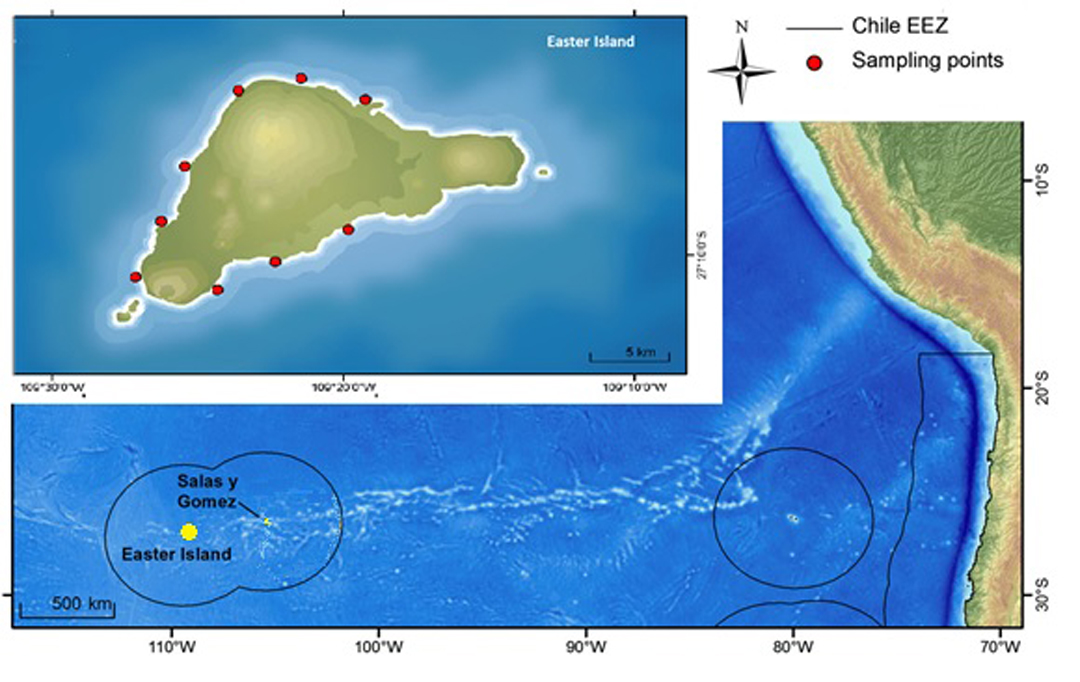

At Rapa Nui, reef fishes are not only a main component of the marine ecosystem, but also a key element of the local culture. Historical fishing around the island has led to the decline of large predatory fishes such as jacks and snappers, while sharks, including the Galápagos shark Carcharhinus galapagensis, are virtually absent. This charismatic species is abundant in the shallow waters around the uninhabited island of Salas y Gomez, located just 400 kilometres (250 miles) east of Rapa Nui. Yet even though they dominate at Salas y Gomez and have been seen at Easter Island by local fishermen, no sharks have been observed in scientific surveys of the latter’s shallow waters. So where are the ‘lost’ sharks of Rapa Nui?

The oceanographic conditions around Easter Island have made its waters some of the most oligotrophic (poor in nutrients and plant life, but rich in oxygen) in the world. Photo © Ivan Hinojosa | ESMOI

Given the extreme fragility of the ecosystem and the need for scientific information, most of the surveys around Easter Island have been made using underwater visual census. This technique has several well-documented limitations, including the effect of divers on their subjects’ behaviour, which makes it less reliable for sampling species such as sharks. That is why scientists from Millennium Nucleus of Ecology and Sustainable Management of Oceanic Islands (ESMOI) of the Universidad Católica del Norte (Coquimbo, Chile), with the support of the Save Our Seas Foundation, are conducting for the first time a survey of fish biodiversity along the coast of Easter Island using Baited Remote Underwater Video Systems (BRUVS), in the hope of finding those ‘lost’ sharks.

Project leader Naiti Morales prepares the BRUVS for the next deployment from a small fishing boat we used for our field surveys. Photo © Erin Easton | ESMOI

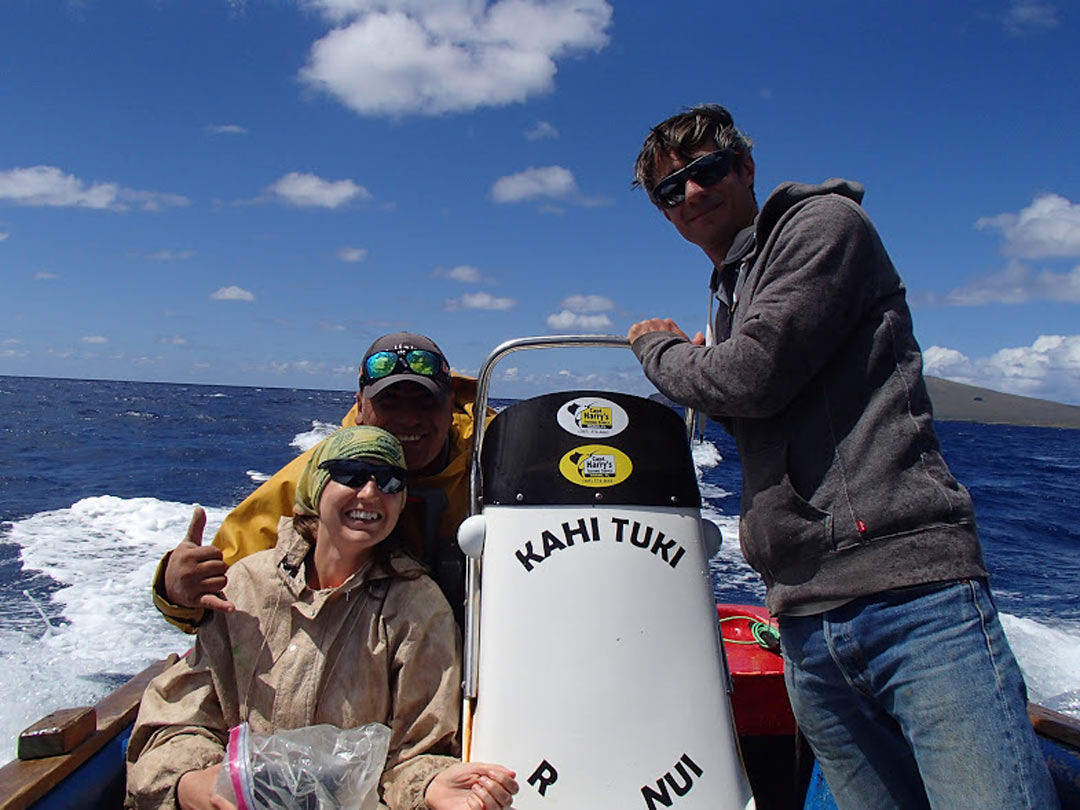

The rest of the ESMOI team: Erin Easton and James Herlan, with Rapa Nui fisherman Alex Tuki on his boat Kahi Tuki. Photo © Erin Easton | ESMOI

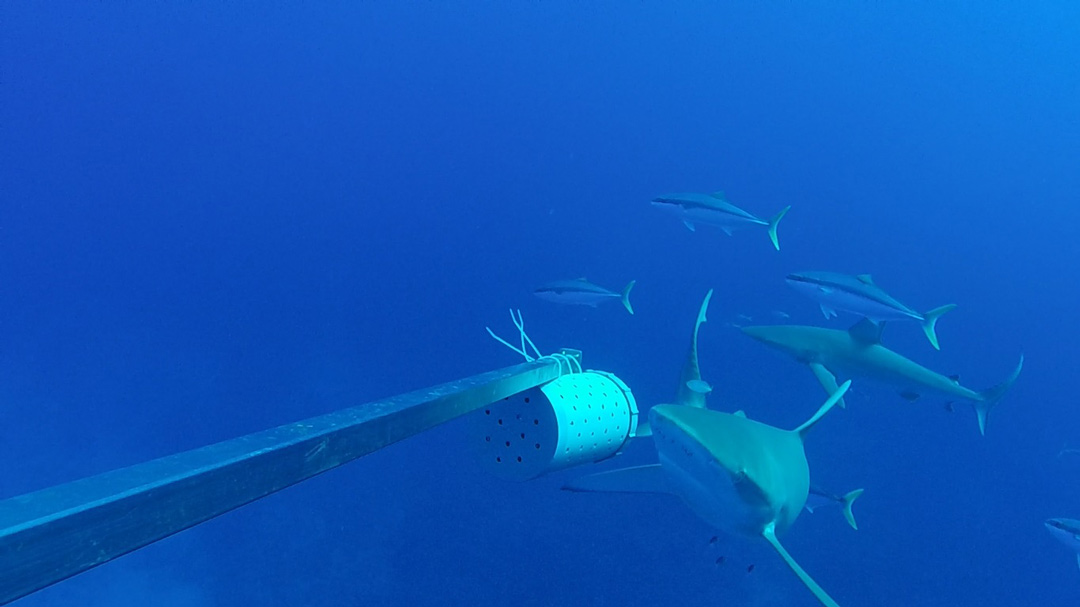

So far, we have completed two of the four planned surveys, one in each season. Our goal is to study the fish assemblage around Easter Island and to determine whether there are any spatial and seasonal differences during the course of the year. The changing weather and scarce supplies on the island have made the study a challenge. Nevertheless, we have been able to record several fish species, including the mango (the local name for the Galápagos shark), which locals claimed they frequently saw while fishing but was never recorded in any other scientific survey for the island. Our study therefore provides the first scientific proof of the regular occurrence of this species in the shallow waters around Easter Island. We can now say with confidence that Galápagos sharks are no longer ‘lost’, but appear to reside off a relatively narrow part of the island.

Diagrams A and B. (A) Location map of Easter Island and Salas y Gomez Island. They lie at the western end of the Nazca Ridge, which is made up of a multitude of underwater sea mounts. The black circles indicate the 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of Chile. (B) The red dots indicate the locations where BRUVS have been deployed. Adapted from Hernandez et al. 2015| ESMOI.

A Galápagos shark approaches the bait while others swim next to a group of yellowtail amberjack. Photo © Naiti Morales | ESMOI

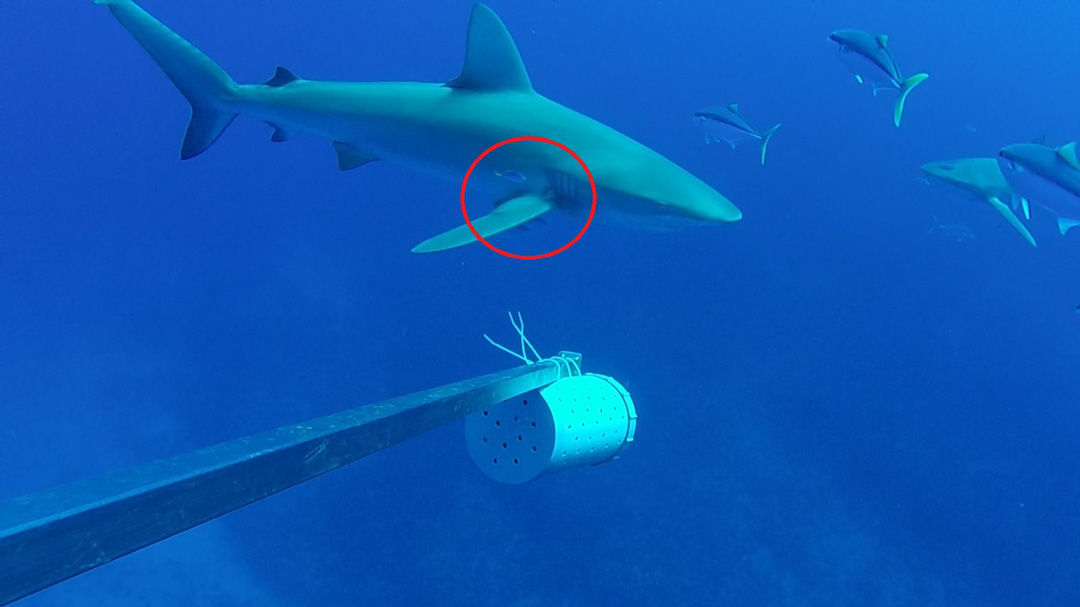

Moreover, the BRUVS videos have shown some new species associations, such as the one between young Galápagos sharks and small thicklipped jacks Pseudocaranx cheilio, which was observed for different individuals and in several videos. This kind of association will require further study to determine the costs and benefits to the species involved.

Local fishermen claim they sometimes see other shark species around Easter Island, including tiger Galeocerdo cuvier, scalloped hammerhead Sphyrna lewini and thresher Alopias vulpinus. None of these species have been scientifically confirmed, but we are confident that the fishermen are right because they know these waters better than anyone else. So keep your eye on our blogs, because one of these days some of these amazing creatures could approach the camera to say ‘Hi!’ – and we’ll also keep our hopes up.

A Galápagos shark swims past the camera, followed by its thicklipped jack companions. Photo © Naiti Morales | ESMOI