Lost and found: a satellite tag recovery story

Things do not always go as planned, and this is especially true in research projects involving wild marine animals. Our latest fieldwork on Florida’s Emerald Coast to study pygmy devil rays in October 2024 was no exception: the weather was only decent for a few days and the rays were hanging out further to the west from Destin where we typically launch from. Fortunately, and thanks to yet another fabulous team effort*, we were able to catch 22 rays, collect numerous samples, and deploy a total of 16 acoustic tags and 7 Wildlife Computers satellite-linked tags. Watch the fieldwork highlights video here!

October 2024 pygmy devil ray fieldwork on the Emerald Coast, Florida, onboard Florida Atlantic University - Harbor Branch’s vessel “the Bateau”. Left: Working up devil rays under the Blue Angels. Right: team photo with a pygmy devil ray. Research activities conducted by Mote Marine Laboratory under FWC SAL-24-1140. Photos © Sean Thomas

The Harbor Branch crew, Kim and I then drove back to our respective labs, 8 hours south in central Florida. The success of our field campaign was soon tainted by a bitter surprise: after only a few days of deployment, the satellite-linked tags were all prematurely detaching from the rays… This was even more frustrating because, prior to the fieldwork, we had practiced and validated the anchoring technique on dissected cownose rays in the lab to ensure long-term tag retention and data recording. After a couple of days watching the tags drift towards shore via Argos satellites, we came to a decision: it was worth attempting a “rescue” mission to recover at least some of these tags. First, for the precious archived data they contain, which have a much higher resolution than the summary data transmitted through satellites; second, to potentially re-use them after refurbishment; and last but not least, for the potential clues on the tags themselves to help us understand why they came off so fast. So there I was, on my first tag hunt, driving back to the Florida Panhandle and beyond (Alabama).

When detached from a ray or a shark, a pop-up satellite-linked tag floats up to the surface and starts transmitting current position and summary data through Argos satellites. These transmissions only last for a certain period of time (generally between 1 and 3 weeks) until the tag battery runs out. One can try to recover a tag from these satellite positions alone, but they are not all highly accurate and generally become available an hour (or more) after the position was recorded. Fortunately, I was able to borrow Harbor Branch’s goniometer: an incredible device which, combined with an antenna, picks up the messages sent by a close-by satellite-linked tag, and provides a bearing and a signal intensity to the user. Depending on the altitude and the reception conditions, the goniometer can detect a transmitting tag within 100 km or more!

Tracking drifting satellite-linked tags on the coast and at sea using a goniometer. Left: The goniometer screen indicates the direction of the last detected signal (center) and its intensity (left). Right: The antenna has to be held as high as possible to maximize detection range, especially in case of rough seas where waves can block the signal. Photos © Atlantine Boggio-Pasqua

It took me some time to adjust to the device and learn how to interpret the bearing indications – they were not always very precise, especially when the tag was still pretty far and the intensity of the signal was weak. I was still evaluating my chances to find any of the tags when, in the middle of a residential neighbourhood of Gulf Shores, Alabama, the goniometer led me straight to a trash bin on the boardwalk. I could not believe my eyes when I saw the small satellite tag lying there in the bag, among soda cans and plastic bottles! What an incredible relief and shot of adrenaline this first finding was!!

First satellite-linked tag recovered in a trash bin along Alabama seashore! Left: can you spot the tag among the trash? Right: a very excited tag hunter. Photos © Atlantine Boggio-Pasqua

Someone had probably picked it up as trash during a beach clean-up the morning it washed up onshore, missing the “research gear” and phone number written on it. Fortunately, two other washed up tags were then reported by local residents, Ben Steiner and Daniel Lutkes, who noticed the inscriptions. I found another tag stuck in marsh seagrass in Perdido Pass thanks to the amazing help of Dr. Ken Heck, a retired marine ecologist of Dauphin Island Sea Lab, and I recovered the fifth (and last) tag at sea, 16 miles off Dauphin Island, in the middle of a 3-foot swell. Unfortunately, the two remaining tags drifted parallel to shore towards Louisiana and weather conditions deteriorated, making their recovery impossible. However, their summary data was successfully transmitted via satellites.

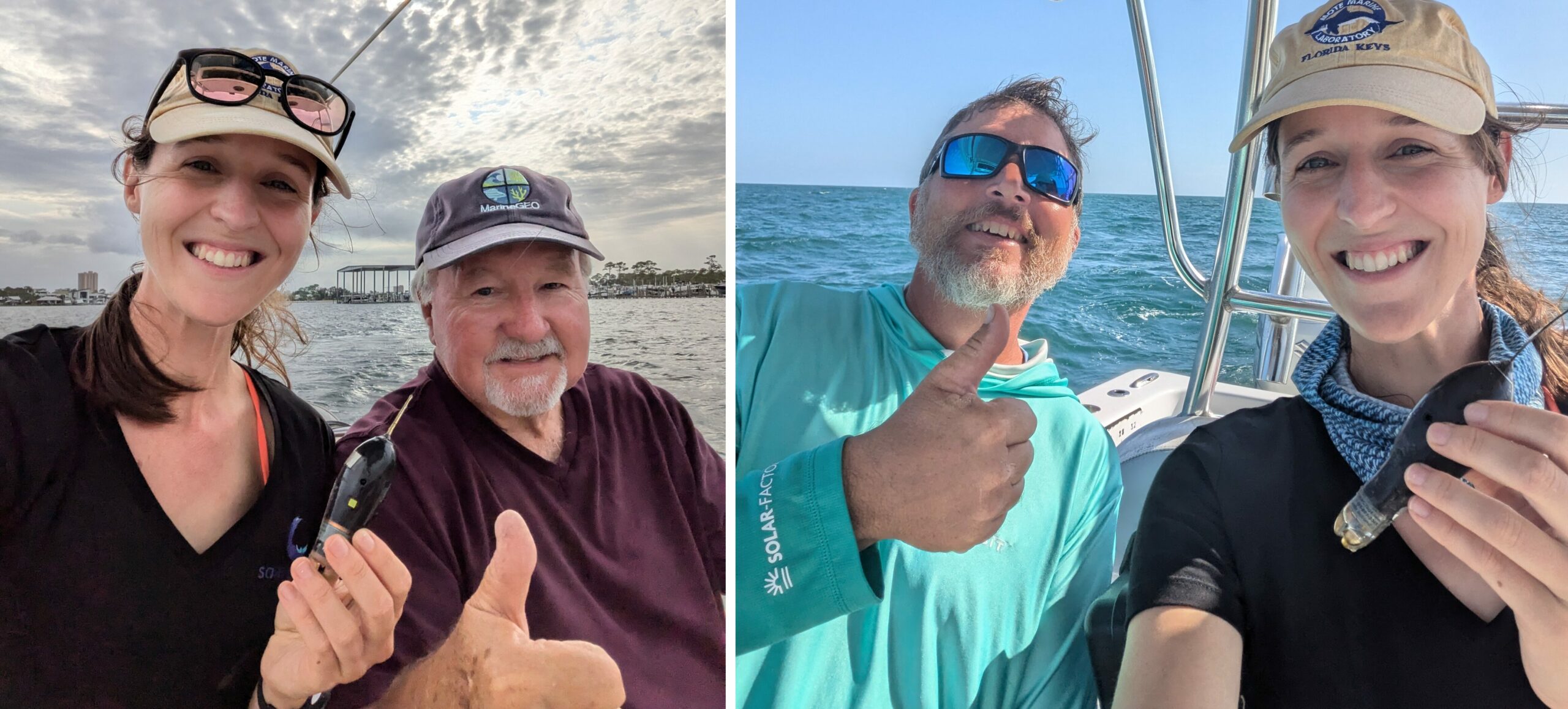

A successful tag hunt thanks to the help of local boat captains, scientists and residents. Left: Perdido Pass tag with Dr. Ken Heck. Right: Dauphin Island tag with Spencer Kight. Photos © Atlantine Boggio-Pasqua

With 5 tags recovered out of 7, this recovery mission ended up being much more successful than expected. And despite the disappointment in our short tag retention, I’m incredibly grateful for this hidden opportunity to develop new skills, meet inspiring humans along the way… and soon work with colleagues to try again, learning from our mistakes and failures. Isn’t this what we call science?

Stay tuned for more project updates!

*Huge thanks to Matt Ajemian and Mike McCallister for being our catch crew this year with the Bateau, to Okaloosa County Coastal Resources Jessica Valek, Mike Norberg and Alex Fogg for all your logistical support in and out of the field, to Sean Thomas and Shane Reynolds for beautifully capturing our work and the species we study, and to all our amazing helpers: Caden Fluegge, Tabby Siegfried, Sam Snow, and captain Kyle.