Locating manatee populations in Africa

As part of my dissertation research, I have just completed a new genetics study that defines for the first time African manatee populations across their large range (21 countries). Over eight years I collected 78 manatee tissue samples from eight countries and successfully isolated DNA from 63 of them in order to determine where distinct populations of the species occur. Collecting the samples was actually the hardest part of the study, because manatees in Africa live in very remote places. Even when samples were collected (from carcasses, live manatees rescued or captured for studies, and from manatee bushmeat in markets), it sometimes took over a year to get the proper export permits to send them to my lab in the USA for analysis.

Lucy working in the genetics laboratory to determine where unique manatee populations exist across Africa.

Most of the samples came from Senegal and Gabon, because those are the countries where I have long-term study sites. Other samples were provided by collaborators working elsewhere in West and Central Africa.

I studied two mitochondrial genes that are commonly used for population genetics because they can inform us about deeper evolutionary levels, and populations rather than individuals. I identified different haplotypes, which are a unique combination of forms of a gene found on the same chromosome. That sounds complicated, but think of haplotypes as ice cream and the different combinations as different flavours. For example, mocha chip and mint chocolate chip are more similar to each other than to strawberry ice cream because they both have chocolate chips. In the same way, some haplotypes are, for the most part, closely related to each other and are from the same population, whereas others are more distantly related and are from different populations.

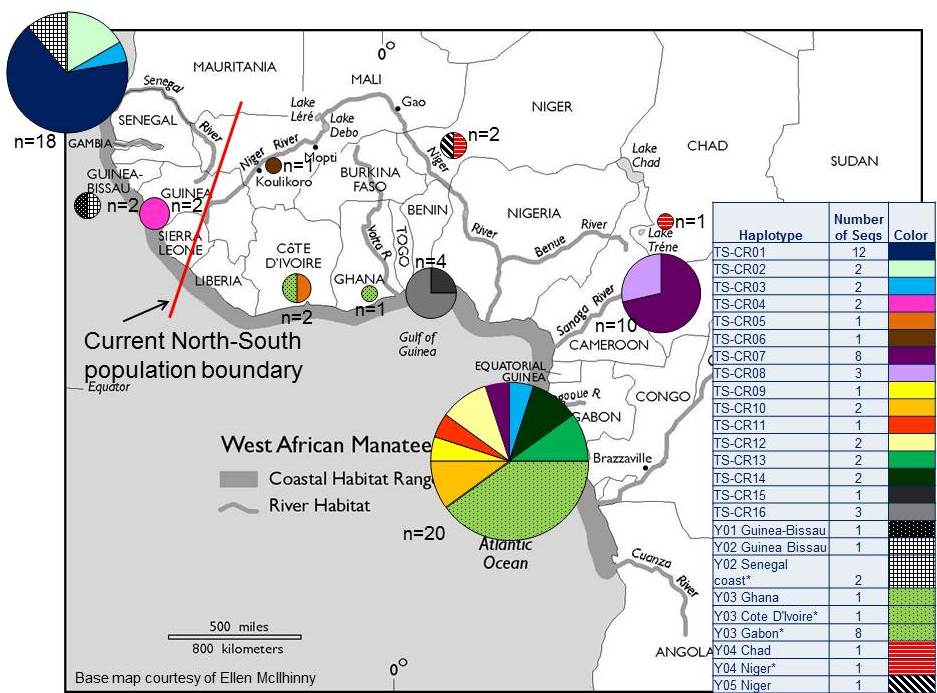

Map of DNA (control region) haplotypes identified in 63 African manatee samples. Sixteen new (solid colors) and five previously published haplotypes (patterns; Vianna et al. 2006) are shown in pie charts. Circle size corresponds to the total number of samples per country, and slices are proportional to haplotypes found (see inset table). Asterisks (*) indicate previously published haplotypes identified at four new locations.

My research identified 25 new haplotypes for the African manatee, which is exciting considering that only five had been recognised until now. The study identified four populations: one in West Africa (coastal Senegal, Guinea and Guinea-Bissau); an inland Niger River population that included samples from Mali, Niger, Chad and Cameroon; a separate population in the Senegal River; and a large population in West and Central Africa (Ivory Coast, Ghana, Benin, Cameroon and Gabon). But this is just a first step and once the study has been published, we will continue to collect and analyse samples in order to continue defining population structure at a finer scale.

By defining manatee populations across Africa, this work aids conservation efforts for the species by informing wildlife managers in many countries about where unique populations exist, where they can focus trans-boundary conservation and management efforts (when populations occur across borders), and where efforts need to be targeted to specific locations in which manatee populations are isolated. My co-authors and I are very excited at the prospect of publishing this work in the scientific literature soon!