Invisible turtle ‘galaxies’ down the microscope – Yep, you read that correctly!

It was a little unreal… It actually worked!

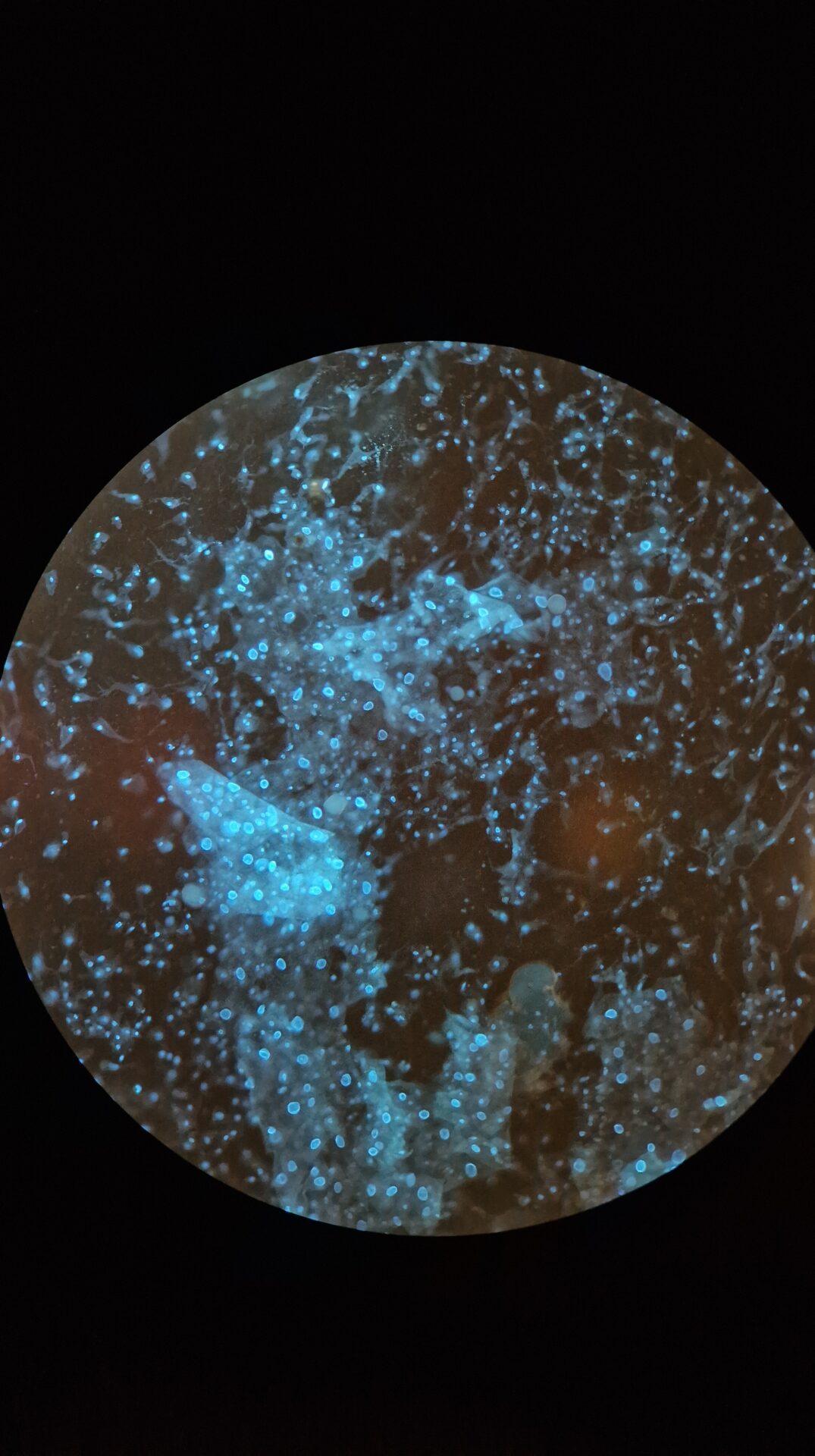

I stared in awe down the microscope at the glowing centre of baby turtle cells, shining like stars in space.

my research supervisor, Dr Nicola Hemmings told me,

– she is one of the brilliant minds that first developed this microscopic technique originally for birds, to assess whether failed, undeveloped eggs were fertilised. Until now, it was never successfully applied to turtles and tortoises in this way, it was no easy task!

You might say: ‘But, Alessia, are they really invisible?’

You tell me – check out the picture of this failed, undeveloped sea turtle egg below:

A failed, undeveloped green turtle egg. Photo © Alessia Lavigne

Can you determine whether this is fertilised or unfertilised by its appearance? Can you see any signs of embryonic development?

Professionals would say “No”, there really isn’t any visible signs of embryonic development. Some may even go as far as saying this is unfertilised…

Now what if I told you they could be ✨wrong!✨. I’ll let you in on the secret. IF the egg was fertilised, baby turtle cells would have began developing at a microscopic level, INVISIBLE to the human eye. Following careful dissection, my method uses a special dye that would stick to the DNA of available baby turtle cells and will glow blue beneath a fluorescent microscope.

JUST LIKE THIS:

Special dyes are used to identify embryonic nuclei in sea turtle eggs as they fluorece bright blue under the microscope. Photo © Alessia Lavigne

‘Ok, but why is this a big deal?’

Turtles and tortoises are facing a global extinction crisis. Their loss can have devastating impacts on ecosystems, as they play essential roles in maintaining healthy environments. By uncovering the causes of reproductive failure, research can pave the way for more targeted and effective conservation strategies.

With this egg, the results tell us that it failed due to early embryo death. Conservation partners will now know to prioritise protecting nests from harsh environmental conditions for example.

Fast forward a few years, I am now a PhD researcher identifying drivers of reproductive failure in threatened turtles and tortoises. I continued testing my methods across several species and finally published these methods and results in Animal Conservation. Our conservation partners are excited as some have already expressed that these results have improved their understanding of hatching failure and helped pinpoint the significant threats to their reproductive success. They feel that the results of this study will inform future management interventions, especially when considering factors such as global warming and climate change.

Alessia Lavigne in the lab holding a critically endangered Hawksbill turtle egg sample that failed to hatch in the field. Photo © Alessia Lavigne