Identifying Wedgefish and Guitarfish

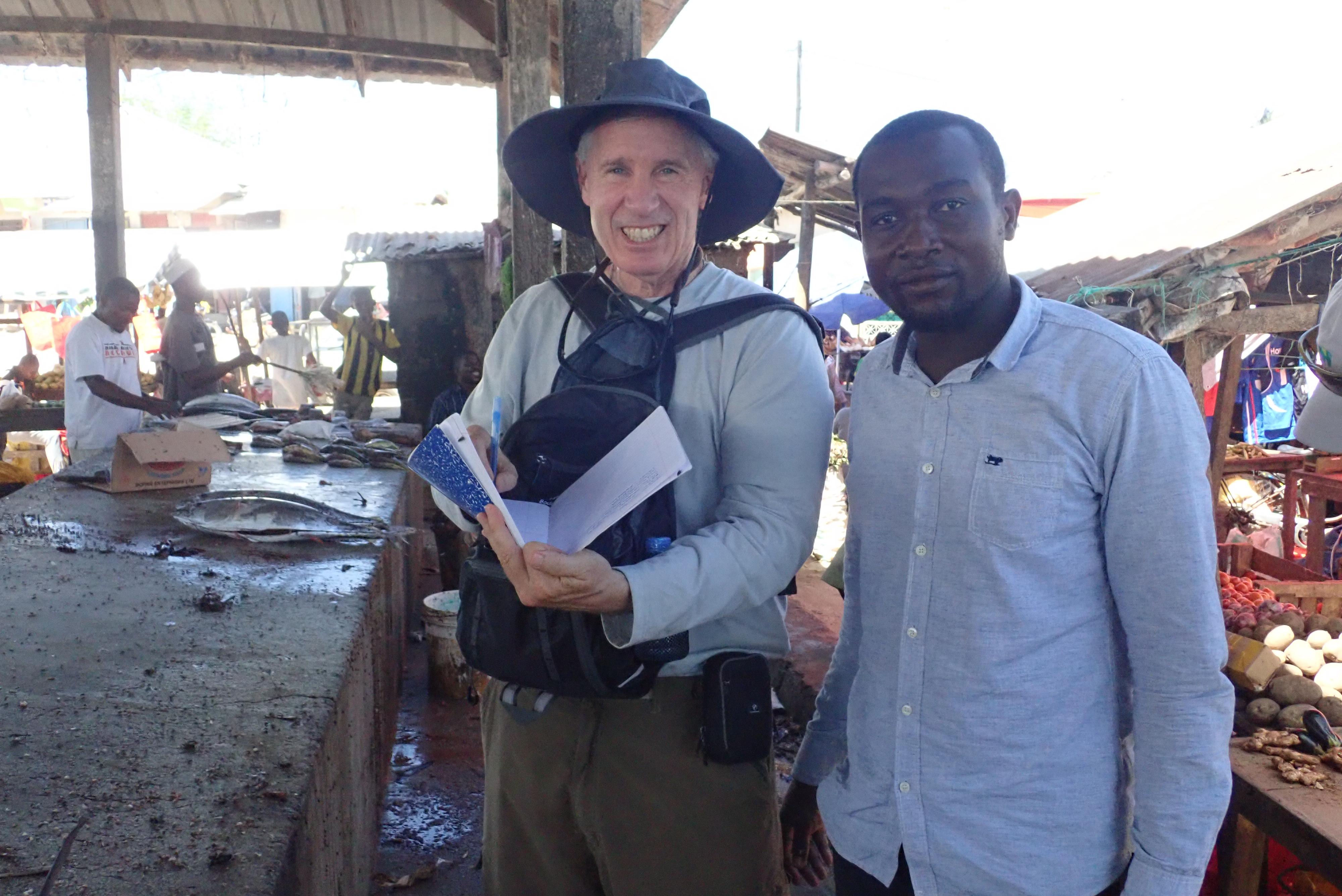

Surveying fish markets in Zanzibar with Rhett Bennett, Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Shark and Ray Conservation Officer. Photo © Marsha Englebrecht

A major problem with monitoring and recording shark and ray species composition data is that in many areas of the world identification guides are almost non-existent or are so outdated that they are of little use to those who most need it. In addition, where guides are available there is a lack of training in the identification of sharks and rays. The good news is that with camera phones observers at fish markets can take pictures that can later be used to identify individual species. However, even taking pictures properly for identification often requires some training so that the key characteristics are included. What may appear to be a cool artistic photograph of a shark or ray may be of little value when used to identify it to species because the key identifying characters are obscured.

Examining rays at fish landing site near Maputo, Mozambique with Wildlife Conservation Society staff, Naseeba Sidat, Jorge Sitoe, and Eleuterio Duarte. Photo © Marsha Englebrecht

Groups such as the Wedgefishes are especially problematic since most are poorly described and the description was based on mostly juveniles, which often have a different colour pattern than the adults. Since Wedgefish are large, some species reaching up to 300 cm total length, the changes in colour patterning with growth can be distinct, with adults of some species appearing plain coloured while the juveniles may have an elaborate, strikingly coloured pattern. Further complicating matters is when multiple species occur in an area it can be nearly impossible to distinguish between species.

Collecting tissue sample for genetic analysis with Abdalla (WCS) at fish landing site, Zanzibar. Photo © Marsha Englebrecht

To remedy this situation, and as part of the “Playing for Time” project a series of regional identification training workshops were held during the first field season of the project. Three workshops were held with one each in Zanzibar and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and another in Maputo, Mozambique. The workshops in Zanzibar and Maputo were translated into Swahili and Portuguese since these are the primary languages spoken.

Surveying fish landing site in Zanzibar with Khamis, graduate student, State University of Zanzibar. Photo © Marsha Englebrecht

The benefits of training local observers are immense given the increasing conservation concern of these shark-like rays. And the workshops are already paying dividends with observers making tentative identifications in the field and then sending them to experts for confirmation. This connection also helps build and maintain relations between the field observers, local conservation organizations, and myself.

Identifying sharks and rays from photographs taken at fish landing sites around Zanzibar with Abdalla, Rhett Bennett, and Michael Markovina (WCS). Photo © Marsha Englebrecht

I have encountered wedgefish throughout my career from South Africa to Japan, but the identification of the species using local guides has been problematic. Most guides list one or more of three species, e.g. White-spotted Wedgefish (R. australiae), Giant Guitarfish (R. djiddensis), or Smoothnose Wedgefish (R. laevis). However, there are eight recognized species and some regions may have four or five species occurring there!

Identifying sharks and rays with Khamis and Rhett Bennett during identification workshop held at WCS field station in Zanzibar. Photo © Marsha Englebrecht

For example, on a survey in Seychelles a few years ago I heard that a violin shark was being landed. Of course the name caught my attention since I had no idea what a violyn shark was? It turns out that in Seychelles the violin shark is actually a wedgefish. In the local guides and scientific literature, the only species listed as occurring in the region was the Giant Guitarfish (R. djiddensis). However, upon examination of the specimen and comparing it with the best available information I had access to, it keyed out to Smoothnose Wedgefish (R. laevis). However, I was not convinced that was it so I called in several colleagues to get a second opinion, which I was glad that I did. My colleague Peter Last (CSIRO) thought it was actually White-spotted Wedgefish (R. australiae), which at the time was thought to be more restricted to the western Pacific and eastern Indian Ocean. A tissue sample was taken and sent back to Gavin Naylor (University of Florida, Shark Research Program) who upon sequencing the tissue sample confirmed it was indeed a White-spotted Wedgefish; quite a range extension from where its previous distribution had been made.

Identifying sharks and rays with Dr. Baraka Kuguru and his staff during workshop held at TAFRI, Dar es Salaam, Tanzinia. Patroba Matiku, back row, second from the left, is also a PI on another SOSF supported project, “What’s going on with the whiprays of Mafia Island? Photo © Marsha Englebrecht

As it turns out, subsequent re-identification of Western Indian Ocean wedgefish has confirmed that the White-spotted Wedgefish is wide ranging and now appears to occur from Mozambique to China, including Australia, and possibly Japan.

Attendees at the identification workshop held at TAFRI, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Thanks to Dr. Baraka Kuguru for hosting the workshop. Photo © Marsha Englebrecht

The recent approval of wedgefish and giant guitarfishes on CITES Appendix II provides a tool in the efforts to conserve these vulnerable shark-like rays. Most species have been accessed as critically endangered by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species due to suspected population declines. The passage of CITES listing for Wedgefish and Giant Guitarfish has only increased the necessity of identifying these shark-like rays to species. Several countries in the Western Indian Ocean are in the process of developing National Plans of Action for Shark, and Rays. Therefore, species-specific identification will be critical in confirming what species occur in these countries.

Attendees at the identification workshop held at Instituto de Investigação Pesqueira (IIP, Fisheries Research Institute), Maputo, Mozambique. Thanks to Stela Fernando (IIP) for hosting the workshop. Photo © David Ebert