Hunting porcupines on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef

The porcupine ray is a really interesting and unusual critter that gets its name from the sharp thorns covering its skin. These rays look something like spiky pancakes, which if you think about it makes a lot of sense. Stingrays are really big, flat ‘meat packages’ that sit on the bottom waiting to be devoured by tiger sharks, bull sharks or hammerheads. But if you’re armoured in tough skin and spikes, you’re much less tempting to a hungry predator!

The unusual appearance of the porcupine ray makes it instantly recognisable – except that most people haven’t seen one. They are uncommon to rare in the Great Barrier Reef; indeed, a year-long citizen science project on the species only turned up a handful of sightings. Many people said they’d never even heard of them. Almost nothing is known about this species and how it uses habitats in the Great Barrier Reef, but there is concern that because it is so uncommon and potentially confined to a specific habitat, it may be one of the species most at risk to habitat loss induced by climate change. To try to find some answers, a small team travelled to One Tree Island in the southern Great Barrier Reef for a mini-expedition to find porcupine rays. The SOSF small grant gave us just enough to get there and to spend seven days hunting for porcupines.

One Tree Island Research Station runs on solar power and rain water. It’s 100 kilometres from the coast and is an undisturbed example of a coral reef ecosystem.

One Tree Island is a tiny speck of an island about 100 km from the coast with nothing on it but a few trees, several thousand seabirds, and a research station that runs on solar power and rain water. However, the large lagoon and shallow bay looked like good ray habitat and the sheltered location made active tracking in boats and kayaks possible. Most importantly, there had been several sightings of porcupine rays around the island, which made it an ideal location for a pilot study.

Strong winds mean that the island’s birds don’t even need to flap; they just glide at head height in the breeze in front of the research station.

The team arrived in late October 2014 to see if we could first locate some porcupine rays and then work out methods to reliably find, catch and tag them. Unfortunately, the weather was not good: strong north-westerly winds made it impossible to use the seine nets we had brought with us. Luckily the weather didn’t affect Plans B, C and D. We deployed Baited Remote Underwater Video Stations (BRUVS) at many sites around the island and lagoons, snorkelled until we were wrinkled, and set fishing gear. The BRUVS have bait bags filled with a secret ingredient chum mix I learned about from Agnès Le Port (Agnès ‘wrote the book’ on short tail rays in New Zealand). The bait bags would attract the rays, which would then be captured on camera. While the BRUVS were filming, we would drop into different parts of the lagoon and carry out snorkel surveys recording habitat variables and any rays we saw. We also used a kayak to conduct surface surveys in the shallows, and fished using long-lines and drop lines to try to catch hungry rays.

The first three days were pretty depressing with nothing to show except bad weather, a flooded camera and lots of ‘zero’ data. We found plenty of other ray species and collected some great footage, but no porcupine rays. Day four brought rain squalls and more bad weather, which would have made tracking impossible even if we’d found and tagged a ray. That night I rigged up and deployed night BRUVS to see if maybe we could find a porcupine ray at night – maybe they were nocturnal? A cold, wet and very late night revealed footage of plankton, crabs and a blue-spotted mask ray Neotrygon kuhlii, but no porcupine rays.

Jury-rigged ‘DARK BRUVS’: doing something different on night three to try to get a glimpse of a porcupine ray.

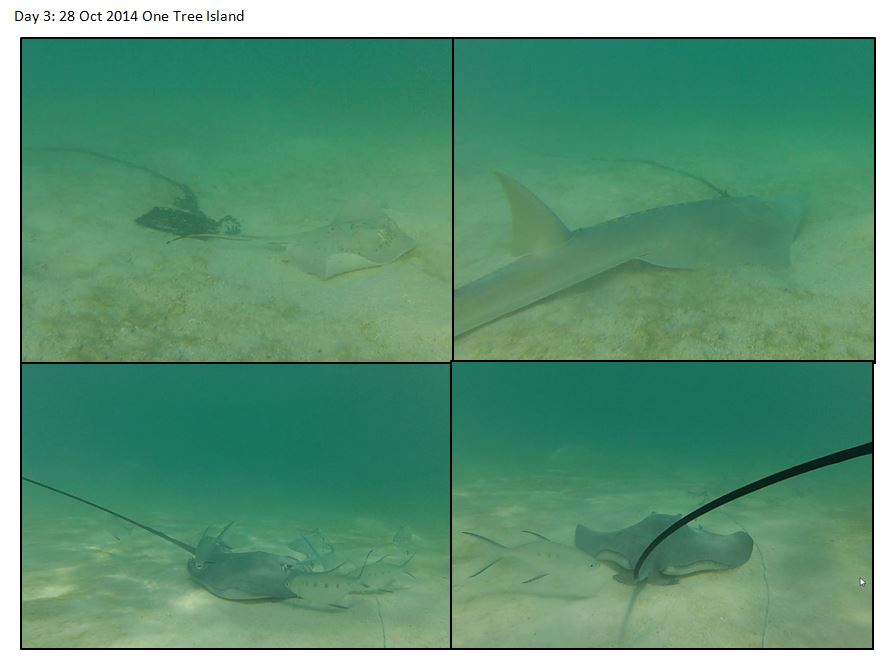

Day five: relief. Calm seas and no wind meant we could get out and deploy the VR2W acoustic listening stations we had brought. After that was done, the team slipped into the now-familiar routine of prepping the boats, deploying BRUVS, conducting snorkel surveys, retrieving BRUVS, downloading footage and charging cameras while eating lunch, conducting kayak surveys, redeploying BRUVS, conducting more snorkel and kayak surveys, retrieving BRUVS, deploying long-lines, deploying drop lines, rebaiting hooks, retrieving . . . repeat. Then late in the afternoon, we finally got a break! In a huge cloud of stirred-up sediment, we got our first glimpse of a porcupine ray sniffling around one of the bait bags and filmed on one of the BRUVS. Hope blossomed; apparently they do exist and they are actually here.

Day five: finally, a porcupine ray is captured on a BRUV! Days six and seven were filled with more porcupine ray encounters; all the rays were large and powerful animals, up to 1.5 m across the disc

The next two days were a blur. The weather deteriorated again, but we had figured out how to find porcupine rays most efficiently using the kayak and in-water snorkellers. The combination of the kayak and snorkellers was very successful as it enabled the team to cover a lot of ground, the kayak carrying nets and the snorkellers ready to attempt capture of any rays found. The rays were usually in several metres of water, so we adapted capture techniques to use three snorkellers: two as blockers with nets while the third attempted to capture the animal by hand. All the porcupine rays we found were large animals, almost 1.5 m across the disc. They were incredibly strong and so large they wouldn’t fit into any of the collection nets we had. We came very close to catching a couple for tagging, but they were just too big.

An eagle ray, with One Tree Island in the background. This was day five, when a rare morning of calm weather gave us a chance to deploy the VR2W receivers.

By the end of the trip, we had 10 records of porcupine rays – not too bad for an uncommon species! We also collected lots of records of other ray species, including data on five of the seven other batoid species I’d hoped to observe at One Tree Island. We had more than 100 hours of video footage and lots of field observations. While the data are still being analysed, preliminary observations suggest that the rays we saw have different feeding and social behaviours. Porcupine rays seem to be among the boldest members of the batoid community, kicking up large feeding plumes and not reacting to divers. I think they may also have high site attachment, and I suspect that many of the animals we saw on different days were the same individual at the same location. Of course, this suspicion can only be confirmed with more data, but the pilot study definitely proved that a longer-term research project to tag and track these animals is possible.

While the pilot study data are being analysed, the lessons learnt from the pilot study are being built into stingray ecology projects at James Cook University. It has become clearer and clearer that we know almost nothing about batoids and yet they are among the most threatened families of the sharks and rays (see Save our Seas Magazine issue 2). We are hoping to return to One Tree Island with larger nets (and hopefully better weather) to tag and track these animals. These future projects will start to provide the information managers need to ensure the sustainable use and protection of these ‘charismatic pancakes of wonder’. #flatsharksneedlove2

One of the VR2W acoustic receivers we deployed during the trip. While these receivers will now pick up signals from some of the other sharks and fishes tagged in the area, we hope to return to One Tree Island to tag rays – and start to fill in a very large missing piece of the reef community puzzle.

To find out more about the Indo-Pacific porcupine ray project visit:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Great-Porcupine-Ray-Hunt-/305641946126804