How to safely catch a hammerhead shark for science

Our lab is very interested in the ecology, migration behaviour and conservation of hammerhead sharks. The great hammerhead is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ and the closely related scalloped hammerhead recently became the first shark species on the United States Endangered Species list (http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/scalloped-hammerheads-become-first-shark-species-on-the-u-s-endangered-species-list/).

Our research gathers data that will help to conserve these amazing animals.

Our studies have shown that although hammerhead sharks are in trouble and need further protection and study (http://rjd.miami.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/BioScience-2014-Gallagher-biosci-biu071.pdf ), they’re also incredibly vulnerable to capture stress and can die even if released (http://rjd.miami.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Gallagher-et-al.-2014.pdf ). This means that our normal research protocols need to be modified.

The research protocols we use for other shark species (http://rjd.miami.edu/research/animal-welfare ) are carefully planned to minimise physiological stress to the animals. The hooks we use are called circle hooks and they’re designed to make sure that they get caught in a shark’s mouth and do not cause internal damage if the bait is swallowed.

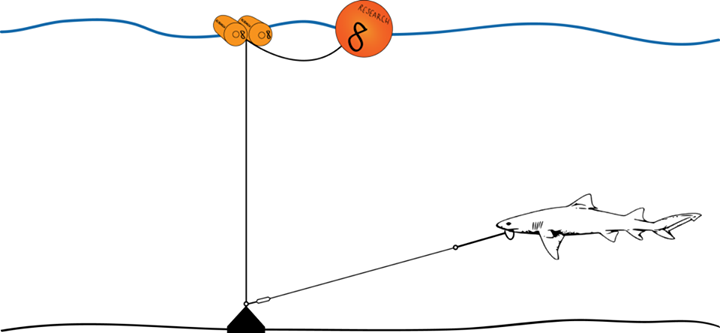

These circle hooks are attached to drumlines, specialised fishing gear that lets sharks swim in large circles after they have been caught. This is important because many shark species need to be able to swim in order to breathe. A drumline is a baited hook attached to a long length of fishing line, which in turn is connected to a weight that sits on the sea floor.

Once a shark has been caught, we bring it alongside the boat or onto our specialised semi-submerged platform. A water pump is then inserted into its mouth so that the shark can still breathe during the research work-up.

A small sample of tissue is taken from a shark’s fin. The data from these samples will be used for my project funded by the Save Our Seas Foundation.

After the shark has been secured, our work-up begins. We take a variety of morphological measurements and tissue samples, which support more than a dozen ongoing scientific research projects. We also apply either a tag with a unique ID code or a GPS satellite tag (LINK: track our GPS tagged sharks here. This research work-up is completed as quickly as possible so that the shark can be released alive and unharmed. It works really well for most of the species we work with, like tiger sharks, nurse sharks, bull sharks and others.

When we catch a hammerhead, we have to move even more quickly than usual to make sure that it’s released alive and unharmed. We sacrifice getting some of the samples and measurements that we take from other species for the sake of the shark’s welfare and safety. But we do still take a small ‘fin clip’, a piece of fin tissue that will be used for my hammerhead shark conservation genetics project, which is funded by the Save Our Seas Foundation. Taking a small sample of fin tissue doesn’t hurt the shark, as there is neither a blood supply nor any nerves in the fin. We also give the hammerhead an injection of prednisone and vitamins before release.

Stay tuned for a future blog post in which I’ll describe how I use these samples to learn about the conservation status of great hammerhead sharks!