From Vitamins to Fast Food: South Africa’s Shark & Ray Fishery

Blog written by Dave van Beuningen. Dave has a passion for the ocean and sharks in particular. Through his work in marine conservation he hopes to change the negative perceptions surrounding sharks and aid in their conservation. Dave is currently the research assistant/technician for Shark Spotters.

South Africa straddles the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, resulting in an extraordinary diversity of sharks and rays. In scientific terms, sharks, rays, skates and chimaeras (cousins of sharks and rays) are together known as chondrichthyans. In South Africa we have over 181 of the world’s 1171 species of chondrichthyan, with 34 of them being endemic to southern Africa, meaning they aren’t found anywhere else in the world! With such an incredible diversity of sharks and rays right on our doorstep, it is overwhelming when we are bombarded with facts like “Did you know 100 million sharks are killed every year for their fins?” Bearing this in mind, I’d be interested to hear your answer to the question “Would you ever eat shark meat?” Unfortunately it’s true. Millions of sharks are targeted for their fins, but what most people don’t realise is that it is much more than just a fin trade. The shark fishery isn’t a recent phenomenon, and you’ll probably never guess how it started.

The first documented account of a targeted shark fishery in South Africa involved using gill nets off the KwaZulu-Natal coast during the 1930’s. Annual landings grew substantially from 136 tonnes in 1931 to over 1000 tonnes by 1940. But why the sudden increase? The answer: because World War II started. Many of the troops during the war suffered from severe malnutrition, and sharks of all creatures were their saving grace. “What’s the connection?” you may ask. Shark liver oil is rich in vitamin A, essential for a healthy immune system and good vision. Shark livers are massive organs and can account for up to 20% of the total weight of the shark, making it a good source of this essential nutrient.

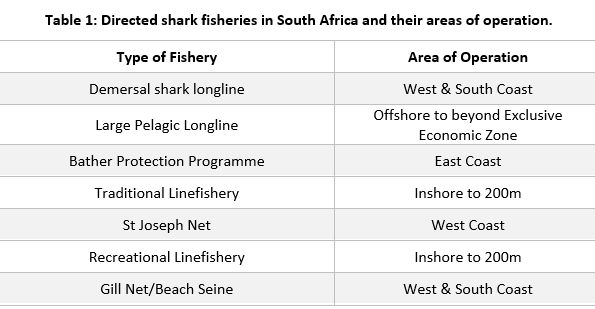

Today seven different fisheries in South Africa target chondrichthyans, these fisheries and their area of operation are listed in Table 1. Of the roughly 180 different species of chondrichthyan found in South African waters, half of them are caught in the various fisheries. This may seem like an extraordinarily high number, but in reality only a fraction of these species are actually targeted, the remainder are generally caught as bycatch. Essentially there are two types of shark and ray fishery, directed fisheries which target sharks and rays, and bycatch fisheries which target other species, like prawns or hake, but because of the unselective nature of the fishery result in non-target species such as sharks and rays also being caught. All the same, the shark and ray fishery in South Africa is big business. But World War II is long gone, and your daily dose of vitamin A can be achieved through the consumption of a few carrots, so why do shark fisheries still exist?

Let me explain a few of the terms here:

• “Demersal sharks” – sharks which live and feed on or near the bottom of the ocean.

• “Pelagic sharks” – sharks which live in the open ocean, far away from coastlines.

• “Longlines” – long fishing lines which have baited hooks attached at intervals along the line. Longlines can be anywhere from 1 – 100 km long.

• “St Joseph shark” – a strange-looking chimaera, and a popular fish to eat.

After World War II the demand for vitamin A decreased, and so did the demand for sharks. The shark fishery stagnated somewhat and during the 1950’s shark meat was primarily sold to other African countries as a cheap source of protein. Only in the 1990’s did the shark fishery pick up again, particularly by the commercial linefishery which saw a surge in shark catches. Heavy fishing pressure on certain valuable linefish species, such as kob and Cape salmon (geelbek), resulted in those populations becoming severely depleted. Consequently the next best option was shark meat. This is characteristic of a boom-and-bust cycle of fisheries around the world, whereby certain high value species are targeted to the point of depletion, and then fisheries move on to the next best option. So, who’s eating all this shark and ray meat? It’s not like we see it for sale in the supermarket. Or do we?

Seafood is the most globally traded food commodity, and seafood fraud is a massive problem. In 2012 a South African study found that 9% of samples from wholesalers and 31% from retailers were labelled incorrectly as a different species. Another concerning issue is that there are no regulations in South Africa preventing shark from being sold under different names, such as “ocean fillet”, “gummy” or “lemon fish”, just several of the thousands of names used to make shark meat sound more exotic and palatable. It’s not illegal for retailers to sell shark meat, but selling shark under different names enables fishers to catch and sell more than the legal limit. Some South African fish and chips shops are taking advantage of this diversity in nomenclature, best to keep that in mind before tucking into a delicious “lemon fish” n’ chips.

Most of the shark and ray processing today is done in and around Cape Town. Small amounts are sold locally either frozen, smoked or as dried shark “biltong”, but the majority is exported. Generally sharks between 1.5 – 12 kg are considered ideal, as sharks over 12 kg can contain high levels of mercury which is poisonous to humans if eaten in large quantities. The majority of frozen shark and ray meat is sold to Australia to be used in the fish and chips trade, with large quantities also being sold to Greece and Italy. All fins are dried and mostly sold to Asian markets. Unfortunately the huge sums of money associated with shark fins provides a strong incentive for targeting larger sharks, even though the meat is potentially worthless. Fortunately South Africa has banned the practice of “finning” (chopping sharks’ fins off and throwing the rest of the shark back into the sea, sometimes still alive), however fins can still be separated from carcasses, but must be landed together with a fin to carcass ratio of 8% for domestic vessels and 5% for foreign vessels. The South African vessels have a higher allowance because the majority of the domestic fleet processes the sharks at sea into “fillets”, discarding more material than vessels that land processed carcasses in the form of “trunks”, essentially the shark with head and tail removed. These regulations apply throughout South African waters and to South African vessels wherever they fish.

What is concerning is that shark and ray fisheries are widely recognised as being unsustainable, although there are exceptions when managed appropriately. Unlike their bony counterparts, sharks and rays are generally long-lived with slow growth rates and late sexual maturation. They also have few offspring with long gestation periods. All in all, they are extremely susceptible to overfishing. Continuous heavy fishing pressure won’t allow stocks to recover, which is concerning for the health of our marine ecosystems. Of major concern is that sharks and rays are often caught as bycatch in fisheries which can withstand a much higher fishing pressure, and sharks also form a large component of unwanted bycatch that is discarded at sea, much of which is unrecorded and unregulated, complicating their management. But it’s not all gloom and doom. South Africa has recently established a National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Sharks which specifically focuses on South African shark and ray fisheries. This report identifies problems within the fisheries and suggests solutions to make it more sustainable. Some of the key issues include inadequate measures to control shark imports and exports, identifying and providing special protection to vulnerable and threatened shark stocks, minimising the unutilised by-catch of sharks and to encourage the full use of dead sharks. It is encouraging to know that our government is taking heed of this global issue and is working towards ensuring the future of our incredible shark and ray diversity. However it is not only up to “them”. You too can make a difference through your choices. Here’s how you can help:

• When buying from a retailer ask them what species of fish it is, if they are unsure, you should be unsure;

• If you’ve never heard the name of the fish before, chances are it may be something you should avoid eating;

• Visit the South African Sustainable Seafood Initiative’s (SASSI) website www.wwfsassi.mobi on your smartphone to see which species of fish are better to eat;

• Use FishMS for on-the-spot decisions about correct seafood choices. Simply SMS the name of the seafood species to 079 499 8795. Soon thereafter you will receive a reply telling you the status of the species concerned and whether you can eat it, if you should think twice or avoid it altogether;

• Visit www.wwfsassi.co.za for more info on the state of South Africa’s oceans.

References

Atkins, H. (2010). You could be eating shark meat and not even know it. Cape Times, May

14, 2010.

Barendse, J. and Francis, J. 2015. Towards a standard nomenclature for seafood species to promote more sustainable seafood trade in South Africa. Marine Policy. 53: 180-187.

Best, L, Attwood, C, da Silva, C & Lamberth, S.J. 2013. Chondrichthyan occurrence and abundance trends in False Bay, South Africa, spanning a century of catch and survey records. African Zoology. 48(2): 201-227.

Cawthorn, D., Steinman, H.A. and Witthuhn, R.C. 2012. DNA barcoding reveals a high incidence of fish species misrepresentation and substitution on the South African market. Food Research International. 46: 30–40.

Da Silva, C & Burgener, M. 2007. South Africa’s demersal shark meat harvest. TRAFFIC Bulletin Vol. 21 No. 2.

Fowler, S. and Séret, B. 2010. Shark Fins in Europe: Implications for reforming the EU finning ban. European Elasmobranch Association and IUCN Shark Specialist Group.

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). 2015. IUCN Red List of Threatened

Species. Version 2014.3. [Internet document] URL: www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed

29/04/2015.

South Africa’s National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Sharks (NPOA-Sharks) (2013). Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries report.

Status of the South African Marine Fisheries Resources. Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries report (2012).

South African Shark Biodiversity Management Plan. Department of Environmental Affairs report (2015).