From the depths of New Zealand to the labs of Spain: a deep-sea adventure

When I first stepped onto the trawler off the coast of New Zealand with the NIWA team, I didn’t know exactly what we would discover. Our mission was to study some of the ocean’s rarest and least understood creatures—deepwater sharks, rays, and chimaeras. These animals live in a world of darkness and immense pressure, far below the ocean’s surface. For most of us, their lives remain a complete mystery.

Here’s the thing: these species are particularly vulnerable when pulled to the surface by fishing gear. The sudden change in pressure and environment is an enormous shock to their bodies. I wanted to find out exactly what happens during this process—how the capture affects their physiology and what we can learn to help protect them.

Blood drawing from a specimen of the deepwater shark Blackmouth Catshark (Galeus melastomus). Photo © David Ruiz-García

Unlocking Secrets in Blood

To get answers, I collected blood samples. It sounds simple, but these tiny vials are packed with valuable information. They hold clues about how stressed these animals are, how their bodies are coping, and what steps we could take to make fishing less harmful for them.

But collecting the blood was just the first step. The next challenge? Analyzing the samples. And the best experts for this kind of work weren’t nearby. Our collaborators at Fundación Oceanogràfic are based on the other side of the world, in Valencia, Spain.

Blood drawing from a specimen of the deepwater skate Smooth Skate (Dipturus innominatus). Photo © David Ruiz-García

A Long Journey for Tiny Samples

Sending blood samples that far isn’t as straightforward as popping them in the mail. They’re incredibly sensitive and need to stay frozen the entire time—no thawing, no mishandling. Shipping them wasn’t an option. Instead, we came up with a better plan: hand-delivery.

That’s where Dr. Brit Finucci came to the rescue. She volunteered to hand-deliver the samples herself, turning into an impromptu courier for science. It wasn’t an easy task—there were permits to arrange, customs checks to pass, and the constant worry of keeping the samples frozen. And then there was the cooler. Brit couldn’t help but laugh at the curious stares and raised eyebrows she got along the way—probably because her cooler looked like it was carrying something much more dramatic, like a top-secret organ transplant. But despite the logistical hurdles (and awkward conversations), she made it happen. The samples arrived in Valencia safe, sound, and perfectly frozen.

Chilly bin transporting plasma samples in the airport. Photo © Brittany Finucci

What Comes Next

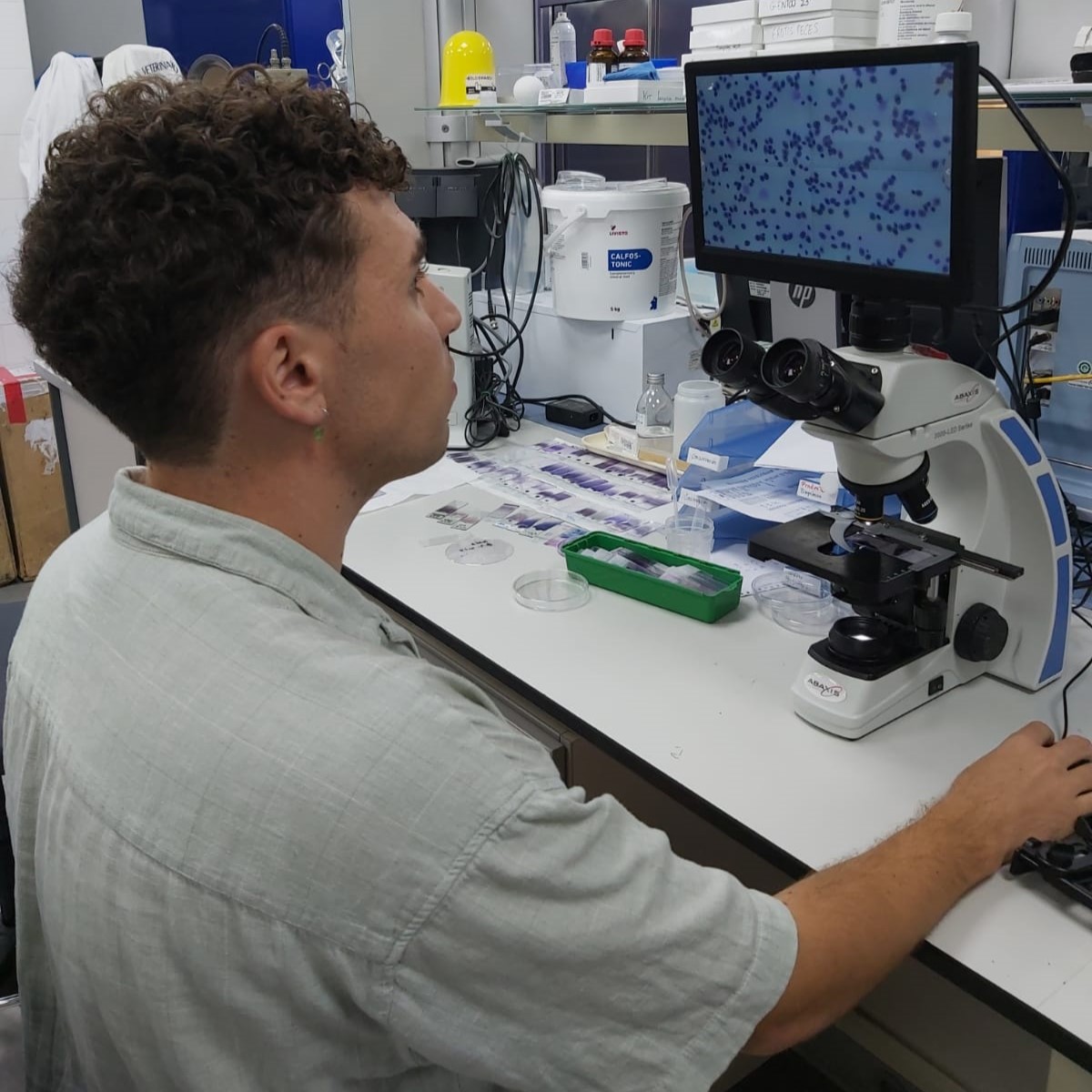

Now that the blood is in the lab, the real work begins. Analyzing these samples will help us understand the physiological effects of capture on these animals. Can we make fishing practices less stressful for them? That’s the big question we hope to answer.

Processing blood smears at Fundación Oceanogràfic lab after their arrival. Photo © David Ruiz-García

Looking back, I’m amazed at how much went into ensuring a few drops of blood made it halfway across the world. But for these deep-sea creatures, it’s absolutely worth it. Each step brings us closer to understanding their lives—and to finding ways to protect them for the future.