Five years on

There is nothing false about the sense of security provided by the Fish Hoek beach shark exclusion net.

The term “shark net” is used loosely to describe many mesh-based shark attack mitigation measures in place around the world. However, it is important to realise that “not all shark nets are created equally” and in fact there are two main types of net that differ dramatically in their applications and their effectiveness at reducing the risk of shark bites in an area.

Traditional shark nets

Traditional shark nets, also referred to as gill nets, are a lethal form of shark control. They are floating fishing devices that are designed to catch and kill sharks in the hope that this reduces the local population of sharks in an area, thereby reducing the risk of a shark bite. They were first used in the 1930’s in Australia and are still used today in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa and Queensland and New South Wales, Australia. These nets do not enclose an area or form a barrier for sharks to enter the beach, they are merely short sections of fishing net that float in the water column and sharks are able to swim around and underneath them.

Many people mistakenly think that these shark nets prevent sharks from entering an area, making it completely safe. This is further confused by official terminology from authorities naming beaches with shark nets as “protected beaches” implying that they will not encounter a shark there. This creates a false sense of security among water users who choose these beaches not realising that over a third of sharks are caught on the beach side of the net, i.e. on their way back out to sea after being in the “protected” beach area. Aside from the fact that these traditional shark nets do not form a barrier, their effectiveness at preventing shark bites has been called into question by experts who believe that reducing shark population numbers through sustained culling programs such as shark nets does not increase beach safety. This was demonstrated in Hawaii where 4,688 sharks were killed over a 17 year period (1959 – 1976) and no reduction in the rate of shark bites was seen, and in 2016 a study at Deakin University in Australia showed that there is no significant relationship between the population size of sharks in an area and the number of attacks.

Traditional shark nets are designed to catch and kill sharks. Photo © Rebecca Griffiths | Sea Shepherd

In addition to their questionable efficacy, traditional shark nets also have significant detrimental impacts on the marine environment. These impacts are not only seen on the populations of potentially dangerous shark species they are targeting. The nets large mesh size and design makes them indiscriminate killers of marine life, with extremely high bycatch rates of non-harmful shark species as well as whales, dolphins, turtles, rays and other animals, many of which are vulnerable or threatened with extinction.

Photo © Sea Shepherd

Accidental entanglement of non-target species (such as turtles and manta rays seen above) is a common occurrence in traditional shark nets. Unfortunately many of these entanglements result in death. Photo © Tom Hughes | Sea Shepherd

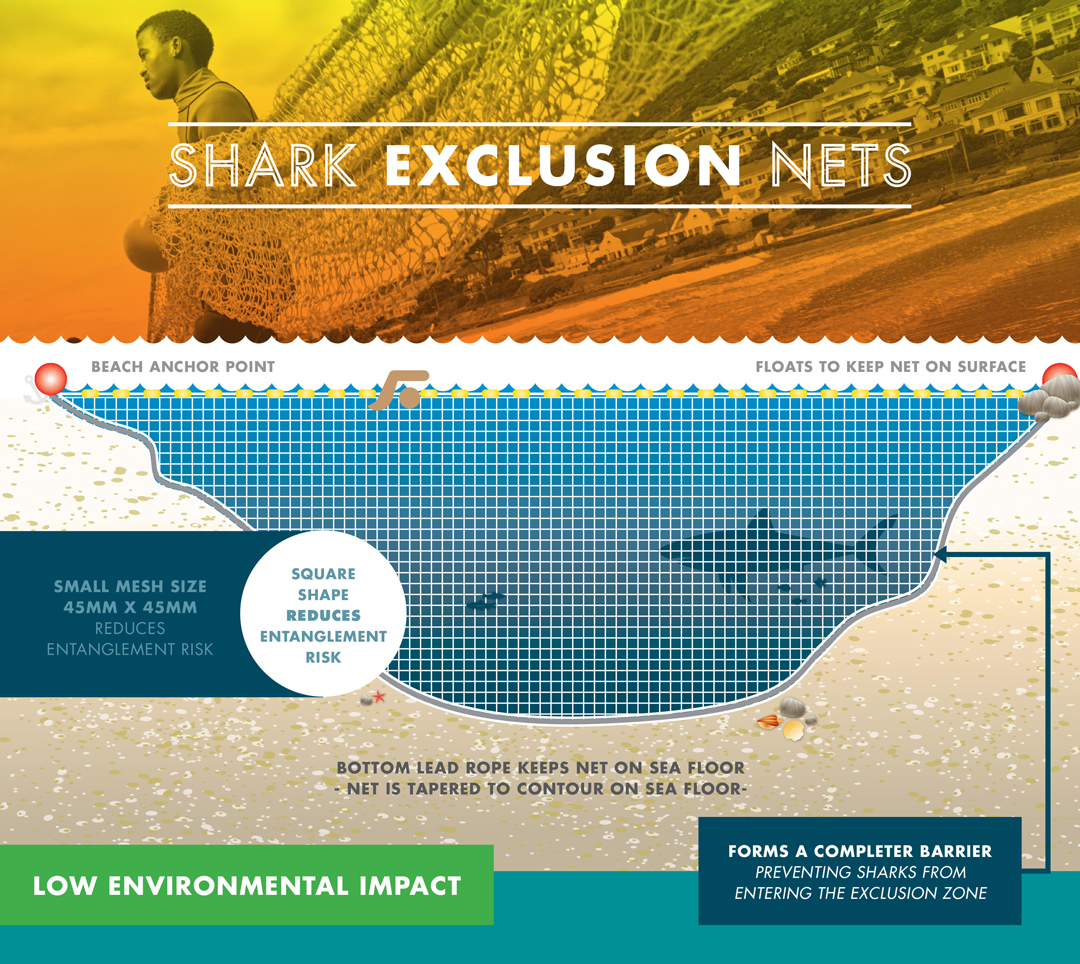

Shark Exclusion Nets

Shark exclusion nets, also called barrier nets, work on a completely different principal to traditional lethal shark nets. They form a complete barrier, from the sea floor to the sea surface, and prevent sharks from entering an area known as the exclusion zone. They are considered a sustainable, non-lethal measure as they typically have a small mesh size resulting in minimal environmental impacts as there is little chance of entanglement of large marine animals such as sharks, whales and dolphins.

Shark exclusion barriers are used all over the world in areas such as Australia, Hongkong, Thailand, Reunion and South Africa. There are many different designs and configurations, with varying materials used, but essentially they all work on the principle of excluding sharks from an area to reduce the spatial overlap between people and sharks, thereby reducing the risk of shark bites.

Photo © Eco Shark Barrier

The Eco shark barrier (first image above) on Coogee Beach, Western Australia is made from a rigid nylon material and has a large mesh size whereas the Fish Hoek shark exclusion net (above) in South Africa has a small mesh size and is made from flexible HDPE twine. Both are shark exclusion nets that have a low environmental impact. Photo © Leigh de Necker

Shark exclusion nets generally cover relatively small areas and are not suitable for beaches with high wind and wave action. They therefore are generally only suitable for swimming activities in relatively sheltered areas, and do not provide protection for surfers who tend to be further out to sea in more extreme environmental conditions. Authorities have attempted to put them in areas with rough seas with limited success. In New South Wales, Australia, the government abandoned installation of two shark exclusion barriers after strong wave action and sand movement damaged the preparatory equipment shortly after they began construction. In Reunion, a man lost two limbs in a shark bite incident that took place inside a shark exclusion net that had been damaged in rough surf conditions.

The Fish Hoek shark exclusion net – a unique success story

In Cape Town, South Africa, we have installed a unique shark exclusion net, unlike any other in the world. The Fish Hoek shark exclusion barrier was first installed in 2013 following a number of shark incidents at the beach that negatively impacted the area. Listening to the needs of the community, the City of Cape Town and Shark Spotters designed and manufactured the worlds first “temporary” shark exclusion net, one which was able to be deployed and retrieved on a daily basis. These daily retrievals reduce the environmental impact as the net is not in overnight when entanglement risk is highest. They also ensure that the net does not get damaged in strong seas as if the conditions are not suitable the net is simply not deployed.

The Fish Hoek shark exclusion net is deployed and retrieved by a crew of 10 previously disadvantaged individuals from the local area. Photo © Wayne Conradie

Since we began in 2013, the Fish Hoek shark exclusion barrier has been deployed a total of 645 times, with deployments focused on the spring/summer period as this is the time with the highest spatial overlap between people and sharks. It has successfully excluded a range of species including white sharks, bronze whaler sharks, hammerhead sharks and short tailed stingrays as well as whales, dolphins and other large marine species. No sharks, whales, dolphins or fish have been entangled in the net. By avoiding the issue of storm damage, the Fish Hoek shark exclusion net has been an extremely low-cost shark bite mitigation measure, costing approximately US$ 25,000 per year to operate and maintain.

Tens of thousands of people use the Fish Hoek shark exclusion net every year. Water users prefer swimming inside the exclusion zone where they generally go in much deeper water than in the open beach area. Photo © Nic Good | Fresh Air Film Crew

The greatest success with the net however has been the response from the water user community of Fish Hoek. Prior to the net being installed, Fish Hoek was suffering from the negative repercussions of multiple shark incidents, including two fatalities close to shore. Many families were too scared to come to the beach and membership of the local lifesaving club declined dramatically. Once the exclusion net started to be deployed a dramatic turn around was seen and the community provided excellent feedback on the net. Parents and children returned to the beach, saying that the shark exclusion net gave them peace of mind to allow their families to enjoy the ocean again, secure in the knowledge that there was an effective safety measure in place that balanced the needs of people and sharks, without resorting to lethal shark control measures. The sense of security provided by the net is a true mark of its success and has even led to unexpected user groups returning to the area, such as open water swimmers who had previously stopped using Fish Hoek as a training area due to shark risk. Now they use the 350m length of the net for training exercises on a daily basis safe in the knowledge that they are protected from sharks.

What originally began as an experiment in 2013 has become a very successful, sustainable, cost effective shark safety solution that has had significant positive benefits on the local community.

For more information about the differences between traditional shark nets and exclusion nets see here.