FitBits for sharks

Solutions for studying wild shark behaviour

Studying the behaviour of wild animals has been a notoriously difficult challenge for researchers over the years. The best way to study animal behaviour is to directly observe and record their behaviours, however, continuously following animals through their natural environment can be challenging, or even impossible, particularly for animals that live in aquatic environments.

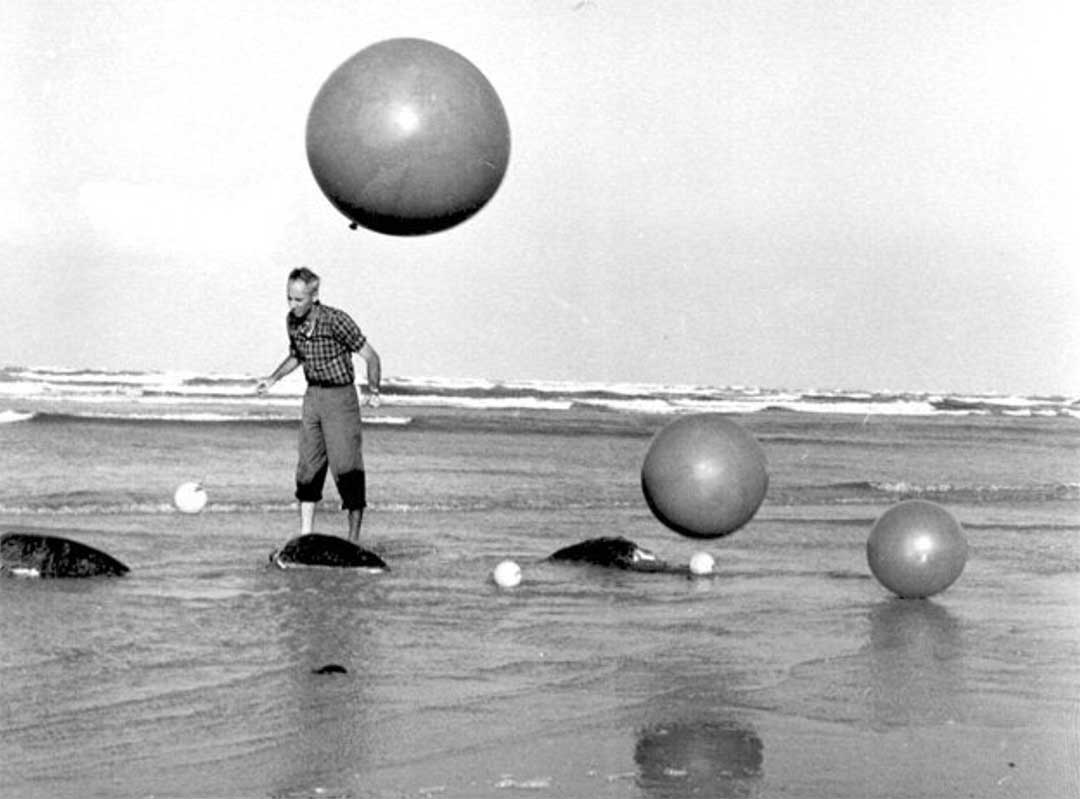

Archie Carr with his tracking balloons attached to sea turtles. Photo © Mimi Carr

Initially, researchers came up with creative solutions to aid in actively tracking (i.e. following and observing) animals for longer, with one of the earliest examples from the 1950s when pioneer Archie Carr attached helium balloons to sea turtles to follow their movements. As technology and techniques developed, biotelemetry tags were born.

At first biotelemetry tags were acoustic tags that transmitted ultrasonic pings that researchers could follow using a hydrophone or by placing receivers around habitats to track movements. As the demand to follow animals over longer and longer distances increased, satellite tags that transmit animal locations to satellites from anywhere in the world were developed. While these tags have drastically increased our understanding of wild animal movements, they only provide locational data, meaning we have to assume animals’ behaviours based on our best educated guesses. This obviously is no replacement for having direct observations to confirm behaviours. Recently, however, the advent of accelerometers has provided researchers with the ability to obtain these long sought after remote behavioural observations.

A satellite tag secured to a shark’s dorsal fin. Photo © Evan Byrnes

An accelerometer sounds like it could be a piece of equipment from a sci-fi movie, but it is actually a simple and common technology that many people come into contact with each and every day. Essentially, an accelerometer is a mini motion sensor that measures the physical movement of anything it is stuck to, and it is the same technology used in FitBits to measure a person’s activity throughout the day. Other applications include triggering an airbag in a car crash or telling your phone when to rotate the display.

So when we stick accelerometers on a shark, the accelerometer continuously records every single physical body movement of the shark at 25 times a second. And because different behaviours, such as swimming, resting, or foraging all require different forms and levels of body movement, we can use the data to determine when the animal was doing different behaviours. Therefore attaching an accelerometer to a shark allows for us to record a detailed diary of that shark’s activity and behaviour throughout the day, almost as if we were directly watching the shark ourselves!

A lemon shark about to be released with an accelerometer is attached to its first dorsal fin. Photo © Michael Scholl

These tags do have their limitations, however. Recording at 25 times a second, results in huge amounts of data, which cannot be transmitted remotely, so researchers must retrieve the actual tag to recover data…but that is a story for the next blog.

Over the past year we have been using these accelerometers to track and investigate the activity patterns of lemon sharks (Negaprion brevirostris) around Bimini, Bahamas. Currently, we have successfully retrieved tags from six sharks, ranging in size from 91 to 144 cm, compiling over 600 hours of data, and over the coming year we will continue to expand this dataset. With this data we hope to examine how the behavioural patterns of lemon sharks varies between different age classes and different habitats to gain a more comprehensive understanding of their home range use.